Flights of fancy

By Michael Roberts

"No one is free, even the birds are chained to the sky."

~ Bob Dylan

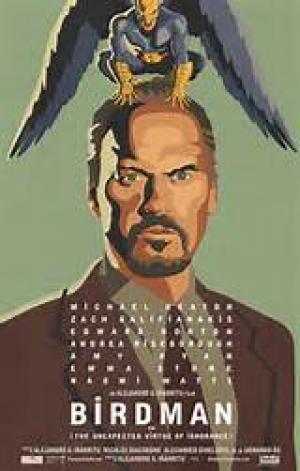

Every now and then an art house film breaks through into mainstream consciousness and reminds audiences of the value of the askance viewpoint, Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Birdman is such a film. After a series of dramatic triumphs with 21 Grams, Babel and Buitiful, the Mexican director delivered his first comedy, albeit a dark one, and resurrected the career of Michael Keaton at the same time as he walked away with the Best Picture and Best Director Oscars . Iñárritu employed Emmanuel Lubezki (noted for his work with Alfonso Cuarón) to helm the cinematography, a demanding task given the piece was shot in a series of extended takes, reminiscent in style and effect of Hitchcock’s trail blazing Rope from 1948. The overtly theatrical piece feels like a play, with a sharp ensemble supporting its central thesis on the nature of celebrity and the tacit and unholy pact that it requires with a brutal public. It also has something cutting to say about the fickleness and frivolous nature of pop celebrity fame.

Riggan Thompson (Michael Keaton) is a fading Hollywood star who wants to gain credibility by producing a play on Broadway. He wilfully chooses to adapt a Raymond Carver story (of course) and battles industry assumptions, public misconceptions, family and fellow cast members as he brings his vision to the stage. He also battles his former alter-ego, Birdman, a Batman like super-hero who hectors him like a Greek chorus, invisible to all and sundry, except Riggan. Like many celebrities Riggan finds that everyone wants a piece of him, and his perpetual motion may be the only strategy he has to keep the cost to his sanity at bay.

Iñárritu layers in many riffs on the ‘pass card’ that celebrity grants to even mediocre talents, in a world where success in mainstream media is all, no matter what formulaic or lame hit propelled the celebrity to fame in the first place. The other side of that coin is that failure, like a contagion, is to be shunned and it is in the tension between those two worlds that Riggan exists. Riggan struggles with the reality of being a washed up celebrity in decline and battles with his own demons of doubt and despair, materialised within his own psyche in the form of his Birdman suited, comic book character. It’s clear that Riggan’s fragile mental state finds him struggling to know where Riggan ends and Birdman begins.

The film captures a period where this celebrity has moved into the “where are they now” category, where the only question Riggan will likely receive will relate to the possibility of yet another Birdman sequel. Far from being content in playing the game and doing the rounds of the second rung talk-show circuit, Riggan tries to gain serious credibility by adapting an ‘intellectual’ piece of literature and debut it on Broadway. The act is bold or ridiculous, depending on your perspective, but for Tabitha Dickinson, a powerful Broadway critic, who has the ability to make or break a show, the decision for Riggan to adapt and direct this kind of a play is a sign of a Hollywood hubris, of an actor getting above his station and of someone who needs to be taken down a peg or two, adding to Riggan’s woes.

Iñárritu also scores points by linking the endlessly vacuous and capricious aspect of social media to Riggan’s dilemma. His oh-so-bored and estranged daughter (Emma Stone) tells him “You don’t even exist” because he’s not on social media, until an accident sees him become a trending topic on Twitter, ironically leading to her connecting to him. His Birdman persona tries to squash the doubts he feels, “You are anything but invisible”, as he manages to convince himself of his strength and abilities, from Yogic flying to telekinesis. In an uncomfortable truth Iñárritu makes plain the sometimes close relationship between extreme celebrity and its unreal demands and a concomitant degree of mental illness. Riggan’s delusions are danced around by an endless succession of sycophants with a vested interest in seeing the golden goose carry on laying golden eggs.

The multitudinous technical challenges of Birdman presented the director and cinematographer with massive logistical problems in order to create a seamless experience that satisfied Iñárritu’s vision based around his observation that, “We live our lives with no editing”. The film is divided into long and fluid takes, all invisibly joined in such a way the piece doesn’t feel forced or the viewer short-changed, in other words the device never overwhelms or fatally compromises the film itself, as it did with the epically tedious Russian Ark. Iñárritu, unlike Sukurov, doesn’t eschew dramaturgy, character or tone for the sake of the concept, and doesn’t lose out with sound and lighting along the way in the same way the Russian film did with its pretentious over-reach. The soundtrack is an energetic and percussive blast that also matches the tone of unease and keeps the film firmly in the realm of the obliquely surreal.

Birdman is a remarkable film full of verve wit and real insight, with a fine central performance from Keaton and brilliant support from the always worth watching Ed Norton and the unexpectedly convincing Zak Galifianakis. Iñárritu’s flair and touch is so sure that the ambiguous ending can be absorbed at several levels, leaving the viewer with much to ruminate on about the nature of reality and human desire, where dreams literally take flight. This dark toned satire was a deserved and bold Best Picture nomination and its win, given its core material is focused on the people in the Academy who vote, i.e. self-absorbed actors, should surprise no-one. For mine the Best Film was Boyhood, but since when did the Academy get it right? That said, Birdman is a fine and worthy piece of cinema and a credit to a brilliant director who will be a contender again, no doubt.