Capital question

By Michael Roberts

“If killing anybody is such a terrible crime,

why does this bloodthirsty chorus go ‘round from time to time”?

- Let Him Dangle by Elvis Costello

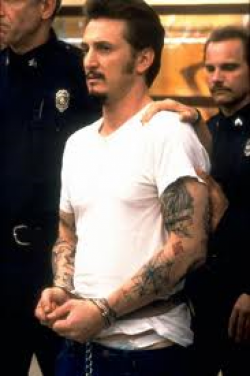

Noted Hollywood liberal Tim Robbins adapted ‘Dead Man Walking’, the book by a Catholic nun, Sister Helen Prejean, about her experiences with a death row inmate. Robbins uses the story as the basis of his morality play, questioning the use of state violence against convicted felons, in a sober and balanced way. Robbins signed up the cream of the American roots music scene to contribute songs to his soundtrack, notably Bruce Springsteen, Steve Earle and Johnny Cash, amongst others, with a notable collaboration between Eddie Vedder and mid-eastern musician Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. Robbins’ then wife, Susan Sarandon, took on the role of the conflicted nun, justly winning an Oscar for her efforts and Sean Pean delivered a pitch perfect performance as the death row, white trash southerner.

Sister Helen (Susan Sarandon), who spends her time amongst the poor and dispossessed of Louisiana, receives a letter from a death row inmate, Mathew Poncelot (Sean Penn), requesting assistance. She agrees to visit him and is warned about the dangers by the prison priest (Scott Wilson), setting up the first point of conflict between her and her patriarchal church. Poncelot protests his innocence in his conviction for murder, and Sister Helen pulls in some legal support for a last ditch appeal. Helen meets the families of the victim, who assume her support of him means she’s taking his side. Helen struggles with the humane impulse to reach out to a fellow human being in need, and the potential for the gesture to offend the victims of the crime. Poncelot picks Helen to be his spiritual counsel during the final days, and she attempts to get Mathew to take responsibility for his actions, and to face up to their consequences.

Robbins approach is deceptively simple; he merely lays out the incidents in a dispassionate fashion and lets the viewer decide. The pacing and tone are more European in tenor, as he’s not afraid to take his time in what is an essentially talky and introspective piece. What resonates in ‘Dead Man Walking’ most is it’s undertone that the trait of empathy is the driving force behind the ability to for one human to connect with another. Helen has dedicated herself to the Christian ideal of the unconditional love of her fellow man, no matter how flawed or damaged that person may be. The challenge for a country like America, that broadly considers itself a ‘Christian’ nation, is to reconcile the gap between the idea that killing any human is against it’s teaching and the state executing individuals on behalf of the population. Robbins points out the rationalisations that are necessary in salving the conscience of a society that sanctions state killing. As Helen points out, “It’s easy for the state to kill a monster; it’s hard for it to kill a human being”. Helen meets Mathew one and one, and finds a human being, not a monster.

Robbins also subtly indicates the socio-economic make up of death row, heavily over-represented by the poor and minorities. “Ain’t nobody with money on death row”, is how it’s articulated. Helen’s battle is to get behind Mathew’s defences, to find out if he truly believes his story of being manipulated by an older criminal into the rape and murder, but blaming the actual killings on the other man. Helen and Mathew are shown in close quarters, Robbins using reflective surfaces to visually code the duplicity in the relationship. Mathew is essentially a two-sided proposition, showing the side that most benefits his story to Helen, manipulating her emotions in the process. As Helen is an attractive woman in a man’s domain there is an inevitable sexual tension to the relationship, and the fact she’s a nun adds a level of taboo to the equation. All of the equation is handled with delicacy and tact by Robbins, who doesn’t over-reach in any area.

The use of death row reprieves as a political instrument by state Governors looking for political advantage is also alluded to, “The last vestige of the divine right of kings”. As long as the ability for the state to execute it’s citizens is tied up with a popularity contest the pitch will always be queered. The imperative for any legislature is to stay above politics, to assert that emotion and rage be taken out of the consideration for appropriate punishment. Ultimately Helen affirms her core idea, regardless of guilt or innocence, and tells Mathew, “Look at me, I’ll be the face of love for you”. Any legal system is doomed to be flawed and will inevitably execute innocent people, and given the primacy of the sanctity of human life in all cultures it’s an odd thing to then claim capital punishment to be part of a civilised society’s suite of measures.

Robbins proves to be a master with his actors, getting career best performances from Sarandon and Penn. Sarandon caps a wonderful run of memorable characters in fine films, including ‘Pretty Baby’, ‘Atlantic City’ and ‘Thelma and Louise’ with her humanist nun, investing great range and feeling in uncovering the depths of emotion required. Penn has rarely been better than the scheming narcissist, who must reckon with the truth, and with the finality of the sentence, as he reveals layers of himself not only to Helen, but also to himself. Robbins also uses the resonance of ‘In Cold Blood’, by casting Scott Wilson in the film, inevitably recalling Wilson’s pivotal role in the true life Truman Capote story and it’s seminal 1967 film.

‘Dead Man Walking’ is an eloquent examination of the death penalty issue and Robbins is wise enough to cover the totality of the issue, not offering simplistic solutions to a complex question. A devastating conclusion, made more urgent by the subtle incremental pressure build, also makes a mockery of the idea of ‘humane’ killing. Once seen, hard to forget.