a slice of Jersey Beat

By Michael Roberts

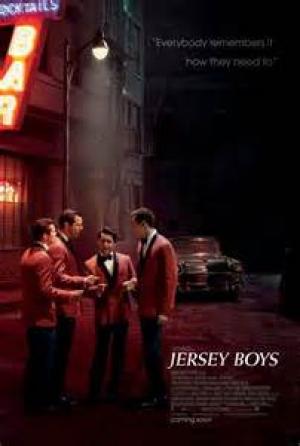

In an era where young singers are sold the furphy that success is available if you “only want it bad enough” and that it will come after an audition on a TV singing show, it’s informative to look at how it was not so long ago. Jersey Boys is the film version of the Broadway musical phenomenon that examines the career of 1960’s vocal group The Four Seasons. The film was originally mooted to be directed by Jon Favreau but after Warner Brothers acquired the rights the job fell to Warner stalwart and Jazz aficionado Clint Eastwood. The cast includes the original Broadway Frankie Valli (John Lloyd Young) and Vincent Piazza as his mob connected friend Tommy De Vito. Jersey Boys is also a film about friendship and love, as Valli steps up to help out the troubled and devious Tommy in spite of advice to the contrary, a pay back for the bonds that 10 years of hard graft as unknowns had built up before fame came knocking.

On the streets of New Jersey the choice for young Italian men rested between the army, the mob or getting famous, like Frank Sinatra. For Tommy De Vito, his brother, and their friend Nick, music is a break from the day to day struggle and petty crime and all through the 1950’s they dabble in various bands, singing standards and trying to get in on the rock and roll boom. It all passes them by until Tommy hears the remarkable falsetto style of Frankie Valli, and after a series of mediocre attempts the group completes the puzzle with the addition of the preppy misfit Bob Gaudio, a talented piano player who wrote his own songs. The group finally convinces producer Bob Crewe to record their song Sherry and they embark on a string on US number one records that make them massively successful, all goes well but soon old wounds start to surface and threaten their stellar rise.

Clint Eastwood might seem an odd choice at first, but his feel for the era and his love of music, albeit Jazz music, has made him eminently qualified to steward the film version. Rather than film the stage show the producers and writers have taken a different approach to the narrative, and for the most part this works fine. The drama takes a central position in the film, as opposed to the stage approach of bursting into song at the drop of a hat, and the songs occur within the historical flow of the narrative, in rehearsal or in recording studios or on tour. This allows the film to replicate a standard dramatic arc, something the stage show avoided, and throws more demand for strong acting upon the players, who all sing their parts as well.

The film lingers on the criminal aspect of the young participants, particularly the part played by Tommy, an opportunist of the first rank and someone with blurred moral and ethical lines. This allows Piazza to shine in the dramatic context, and he is the fulcrum for much of the first half, before the music takes centre stage. Valli is the conflicted friend who tries to support the unpredictable Tommy, but finds a better way when the clean cut Gaudio arrives, allowing him to focus on his ‘gift’, his incredible falsetto voice. Gaudio says, “When I first heard that voice I knew I had to write for it”, and it’s a pity that every singer who plays Valli in the stage show, no matter how good they are, cannot hope to duplicate the effect. The gap is exposed when the soundtrack finally plays a couple of original recording during the credits, their flair and energy and sheer joy leaving any imitation in the shade.

The film has so much ground to cover, and given it doesn’t take the fractured, impressionistic approach of the show, it can’t convey information in a single line and cut away to a fresh song or scene, which makes some of the scenarios seem less than complete. The Italian boys from Jersey have grown up in a culture where the men do what they like, and any woman who dares to push back is a “ball breaker”. The time restrictions of the film have limited the women characters in it to being ciphers, rather than fully fleshed out figures, so it’s best to concentrate on the music that’s presented. The writers also sensed they had a ‘Rashomon’ situation, having interviewed all the surviving key players, and their attitude is best summed up in one of Tommy’s lines, “Everybody remembers it how they need to.” Best not to read Jersey Boys as definitive history, but as a series of perspectives with some license taken, as with Bob Crewe, shown here as an overt and flamboyant gay when in reality he was a closet gay man.

As a vocal group that came out of the mean streets of New Jersey in the early ‘60s, in the wake of the New York Doo-Wop groups of the ‘50s, The Four Seasons filled a crucial gap between the original burst of rock and roll and the fresh blast of the British Invasion. The uber-melodicism of their tunes saw the group enjoy three successive US number ones with Sherry, Big Girls Don’t Cry and Walk Like a Man before The Beatles came along and changed the game for good. The Four Seasons were not a ‘beat group’ per se (like their West Coast competitors The Beach Boys) they were a throw back to Doo-Wop harmony groups like The Chords or The Diamonds, and unlike other beat groups their musical values also incorporated the romantic tenor traditions of Broadway.

Gaudio wrote complex musical changes that belied the three chord rock and roll ethos that dominated the industry at the time, more in line with the tunes found in Gershwin, Jerome Kern or Cole Porter, giants of the American Songbook. The film avoids the fact that The Four Seasons could not adapt to the changing musical scene, in fact in the wake of Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde, The Beach Boys Pet Sounds and during the time the Beatles were making Sgt Peppers, Valli released his cheesy but catchy ‘club-land’ classic, Can’t Take My Eyes Off You, hardly cutting edge Summer of Love artistry. They were a band out of time, and despite the problematic personal issues regarding Tommy’s mob debt, there was no indication they had the ability to change and join the musical revolution going on around them.

The film works as a record of the circumstances surrounding some fine singing and great, timeless melodies, not as a documentary of artists at work. The break up details certainly makes the fractious late history of even The Beatles look tame by comparison, and the mob stuff is effective, as is Christopher Walken’s turn as the interested local gangster. If the characters don’t come off as fully rounded it’s because the piece is caught between the fluff of a ‘let’s put on a show’ ethic and the sense that gravitas needed to be added via the mob subtext, and the two do not easily cohere. The music industry in the 50’s in New York was notorious for the mob influence that permeated every level from production to distribution, but to elevate that side of the tale runs the risk of unbalancing it. That said, the music is wonderful, the songs endlessly catchy and the direction vivid and detailed.

Eastwood walks the tightrope with finesse and skill, proving why he is one of America’s premiere essayists, his eye for detail and for authenticity does not let him down. He manages to include a couple of neat comic throwaway lines with a background TV playing Rawhide and with Joe Pesci (Joey Russo as the actor as a young man) asking of his friend who says he’s funny, “I’m funny, how”? Wisely Eastwood avoids applying a West Side Story type element until he tacks on the December ’63 song as the ebullient finale, which works fine in context.

The film wins as a tribute to a great musical form, even if it won’t win any cinema awards, and it’s the perfect reminder of how good the original Four Seasons were, when a small but golden window opened up for them and they took their turn in the sun. For music buffs it will inevitably have us reaching back to the original recordings, and basking in their rich harmonies and beautiful noise, and that can’t be a bad thing.