French Hitchcock II settles debt with French Hitchcock I.

By Michael Roberts

"A woman confronting men is a proper subject, it is inexhaustible."

~ Claude Chabrol

Of all modern French films this one has the most compelling antecedents, being as it boasts input from the ‘French Hitchcock’, or more accurately, both of them! In the mid ‘60s, L’enfer was the project that nearly killed the legendary Henri-Georges Clouzot, who spent years in writing and making visual tests for his version, only to abandon it after he suffered a heart attack. Some 30 years later, and 17 years after Clouzot’s death, his widow Inès passed his three written drafts of L’enfer to Claude Chabrol, who took the first draft and adapted his own version for this 1994 film. The dripping irony in all of this was that Chabrol should finally be the one to bring the project to the screen, as he was the man who took the mantle of the ‘French Hitchcock’ from Clouzot. To heap irony upon irony, Chabrol was also someone closely associated with the Nouvelle Vague movement, the collective of ex-film critics who had scathingly dismissed Clouzot’s body of work as cinema du papa.

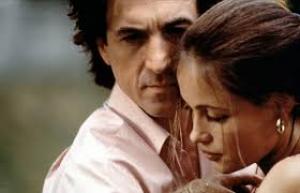

Paul (François Cluzet) is a young man building his dream, a renovated hotel in near a lake resort town, when he falls in love with the gorgeous Nelly (Emmanuelle Béart). The young couple marry and have a son, and all seems well in the garden, but after a few years Paul finds juggling the demands of the business with his family is becoming more and more difficult. After half a dozen years of marriage Paul starts to suspect the beautiful Nelly of having an affair, and soon his life spirals into a pit of jealousy and despair.

Paul’s descent into a state of delusion is handled deftly by Chabrol and delivered via a powerful characterisation from François Cluzet. Chabrol builds the picture with devastating detail, delivering clues and morsels along the way of the kind of thought process Paul is experiencing. Paul imagines that a small illness in his son is actually a cancer; indicating that he will take a tiny thing and extrapolate to something disastrous. So it is with the smallest of looks that Nelly gives to other men at the hotel, looks that Paul soon turns into a series of imagined betrayals.

Cluzet had worked for Chabrol before, twice in the early ‘80s, and stepped up as a mature actor to take the demanding role of Paul. Cluzet provides a subtle and nuanced characterisation of a deeply tormented man that stays in the memory, and in many ways it announced his arrival as a leading man of the first order in French cinema. Cluzet walks a difficult line, evincing sympathy for Paul in the early scenes, but losing all support as he becomes irrational and deluded. In Clouzot’s original, Serge Regianni got ill on the first week of shooting which doomed the ill-starred project from the start. Cluzet went on to become a big star in French films, with stand out performances in the excellent psychological thriller Tell No One in 2006 and in the hugely popular The Intouchables in 2011.

Emmanuelle Béart more than equals Cluzet’s performance for intensity in her heart rending role of the beautiful wife under suspicion. Béart also masters the duplicity required for the early scenes which leaves us unsure as to the actual level of betrayal, which plays brilliantly in support of the tone of ambiguity that Chabrol maintains throughout. Chabrol knows that layering a mystery element adds to the intrigue and gives the jealousy angle something to rub up against, as a solely relying on that alone would make for a bleak film indeed. Béart had made her name in Claude Berri’s massively popular Manon des Sources, but would come into her own as an actress in a couple of 90’s films in Jacques Rivette’s The Beautiful Troublemaker and Claude Sautet’s A Heart in Winter, with Daniel Auteuil, her then partner and future husband.

Claude Chabrol was the master of psycho-sexual cinema, and his command of the thriller genre led to the superficial tag that had attached itself to Clouzot in days of yore. Clouzot had beaten Hitchcock to the rights for Les Diabolique, in the early ‘50’s but in reality he looks more like a French Kubrick, a demanding, obsessive and meticulous perfectionist who had poor social skills. Chabrol maintained a delight in the dark humour of the macabre, so in this regard he was closer to Hitch than Clouzot, and a sense of humour is not something readily associated with either Clouzot or Kubrick.

L’enfer may have been a labour of love for Chabrol, but it is more than just an exercise in paying homage to your peers or paying back a debt owed by he Cahiers critics who had unfairly dismissed the work of Henri-Georges Clouzot, it is a fine and biting entry in the late Chabrol canon. Chabrol had proved himself worthy of the sobriquet of the ‘French Hitchcock’ with his string of impressive thrillers in the ‘60s and ‘70s, but in truth he cast his artistic net wider than the master, as evidenced by his classic adaptation of Flaubert’s Madame Bovary with the singular Isabelle Huppert from 1991, or his comedic, The Swindle with Cluzet and Huppert in 1997.

Claude Chabrol made a body of work across 51 years that stands with the best directors in World Cinema. He kick started the Nouvelle Vague (of which he said "there is no new wave, there is only the sea") and virtually outlasted them all as a relevant and vibrant voice in the cultural life of France. L’enfer is a worthy and intriguing film and one that sits nicely within the upper echelons of his legacy. C’est formidable!