Picture yourself in a boat on a river....

By Michael Roberts

"Nature, Mr. Allnut, is what we are put in this world to rise above." ~ Rose to Charlie.

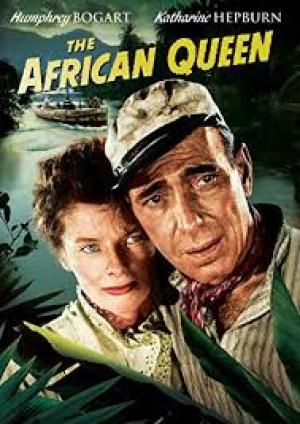

After crafting several classic films together, director John Huston and star Humphrey Bogart set off for Africa in 1951, in league with Katherine Hepburn, to put together what is undoubtedly their most light-hearted movie together and a ripping adventure yarn, The African Queen. Taking as his source material C.S. Forester’s 1395 novel of the same name, Huston crafted a witty screenplay (In tandem with Peter Viertel, James Agee and John Collier) that simply showcased his marquee stars to best advantage, even if he had to change Bogart’s character to Canadian because Bogie couldn’t get a cockney accent down (hello Dick Van Dyke). He dragged ace British cinematographer and Powell and Pressburger favourite, Jack Cardiff along to the Belgian Congo to shoot the piece in a riot of colour and captured the heat and romance of the jungle in an unlikely love story between two middle-aged people stuck in their ways, until a WWI call-to-action intervenes.

Rose Sayer (Katherine Hepburn) is an English Christian missionary in a German colony with her Reverend brother Samuel (Robert Morley) in deepest, darkest Africa on the eve of the Great War. Their Godly work is interrupted by Canadian river boat Captain, Charlie Allnut (Humphrey Bogart) who informs them of the outbreak of war between Britain and Germany and the dangers of staying in a German controlled colony, but they refuse his offer to help them leave. The Germans arrive and injure Samuel, leading to his death and Rose escapes with Charlie in his boat, The African Queen as they make for safety. The pair navigate the hazards of the jungle as well as the dangers of the Germans as they make their way down river before Rose has a plan to sink a German boat that patrols a large lake. The couple strike up an unlikely friendship as Charlie attempts to deal with Rose’s mad scheme, but he becomes caught up in her zealous fervour and soon finds himself aiding her against his best judgement.

In many ways the scheme to scuttle the Germans by homemade torpedo is a classic McGuffin, it just doesn’t matter to anyone else and is merely the device to propel the action for the two protagonists. That created a problem with the ending as the novelist never liked the ending he had and James Agee had a heart attack before finishing the script with Huston. Katherine Hepburn was livid about the lack of detail and disliked Huston’s odd methods but took Bogart’s advice to trust the maverick director. Huston engaged Peter Viertel to help with the ending and after determining it needed to be a happy one for the film (as opposed to the book) they concocted a clever conceit that led to the requisite death of the bad guys and escape of the good guys. Peter Viertel wrote a partly fictional book in 1953 on his African adventure, called White Hunter, Black Heart, and it wasn’t until 1990 that Clint Eastwood made it into a film that gave something of a taste for what transpired off-screen. La Hepburn also wrote a book years later in 1987, The Making of The African Queen, Or How I Went to Africa with Bogart, Bacall and Huston and Almost Lost my Mind, where she outlines the various struggles the crew encountered.

Bogart and Hepburn play the piece with such style and charm, milking every ounce out of the odd-couple pairing, that the developing and deeper feelings they confront feels entirely organic and appropriate, a tribute to Huston’s sure handed direction. The film is the embodiment of the concept of a ‘star vehicle’ and even though the circumstances of the production were very difficult the results speak for themselves. Bogart, a city man through and through, hated every minute of being in Africa and only survived the ordeal by imbibing huge quantities of scotch whiskey and accepting the ministrations of his gorgeous young wife who acted as nursemaid and general help for the company. Hepburn, on the other hand, loved Africa and embraced all it had to offer in the exotic stakes, even accompanying Huston on a hunting expedition that almost went pear-shaped and threatened their lives. Bogart said of Hepburn, "Katie was in her glory. She couldn't pass a fern or berry without wanting to know its pedigree and insisted on getting the Latin name for everything she saw walking, swimming, flying or crawling. I wanted to cut our ten-week schedule, but the way she was wallowing in the stinking hole, we'd be there for years."

The theme of middle-aged love and attraction was virtually unheard of in Hollywood, indeed RKO had toyed with the idea of adapting the novel for Charles Laughton and Elsa Lancaster in the late ‘30s but decided no-one wanted to see a love affair develop between two “physically unattractive” people. Why the situation in the film works so well is the oppositional forces in play - Rose denies the ‘natural’ world, the physical and the corporeal and Charlie is all about the natural world, having no conception of Rose’s higher, more pure yearnings. Rose is all about order, the order of God’s design, whereas Charlie is about chaos and flying by the seat of his pants. The delight is both of them coming to see something of the other in themselves. Rarely has Hepburn's haughtiness, perceived or real, been applied to greater effect, and Bogart's discomfort was not a stretch given his dislike of the location, but he plays a loveable rogue with aplomb and conviction.

Huston had the good sense to push for Technicolour and location filming, forcing producer S. P. Eagle, Sam Spiegal into a deal with Romulus Films out of the UK. It was an era of International co-projects and out of the success of The African Queen Spiegal stayed in London with his Horizon films and eventually made three best Picture winners in On The Waterfront, Bridge on The River Kwai and Lawrence of Arabia. Huston indulged his passion for game hunting while he was in Africa and matched Bogie glass for glass, but the whole team became fast and lifelong friends, as witnessed by Hepburn’s lovely telling of Bogie and Spencer Tracy’s last meeting just before Bogart’s death in 1957.

John Huston pulled all the disparate parts into a coherent whole, outdoor shots and studio set-up’s and his fine direction garnered nominations for both Bogart and Hepburn. Hepburn lost to Vivien Leigh in A Streetcar Named Desire but Bogart finally won, beating Brando no less, and fittingly he became the last "last century man" to win. The African Queen is a classic Hollywood popcorn film that luxuriates in all its key elements; location, stars and beautiful cinematography, it’s neither deep, nor political, pure escapism in a world still recovering from WWII. A timeless, sparkling gem, a keeper.