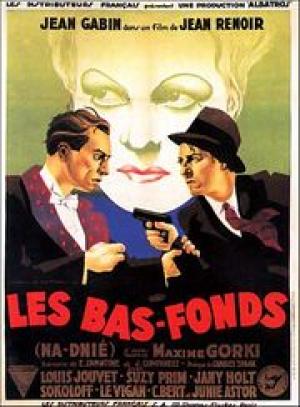

Renoir, life. still.

By Michael Roberts

'All technical refinements discourage me. Perfect photography, larger screens, hi-fi sound, all make it possible for mediocrities slavishly to reproduce nature; and this reproduction bores me. What interests me is the interpretation of life by an artist. The personality of the film maker interests me more than the copy of an object.'

~ Jean Renoir

Jean Renoir produced one of the pivotal works of the French poetic realism movement with this film. Renoir bought together a potent mix of talent and source material, using Maxim Gorky's play as his starting point, although he described the changes he made as “enormous”. This marked his first collaboration with the iconic leading man Jean Gabin, and they quickly became great friends and made a trio of unsurpassed masterworks in as many years. It was during this period that Gabin established himself as the embodiment of masculine French cinema with an astounding run of superb films probably unequaled in any country in any era.

In The Lower Depths, Pepel (Gabin) is a born thief, conforming to his societal circumstance - it’s his ‘costume’. The brilliant Louis Jouvet, a different kind of masculinity to the gruff Gabin, is counterpoint to Pepel as the Baron who loses his position, his costume, through a gambling addiction. Circumstances throw together the two men, outwardly from different worlds, and this where the commonalities are revealed. Gabin is all restraint and understatement, he has no need to shout and bluster and the character benefits from the choice. It makes his rage, lurking underneath, all the more effective once it’s unleashed. As with most of Renoir's work, this film is about escape for the individual, physically and mentally, and of course once more, love will light the way.

Pepel has been having an affair with Vassilssa (Suzy Prim), the wife of the greedy owner of his lower depths flophouse, indeed at one point she wants Pepel to kill him so they can be together. He is sick of her scheming ways and longs to escape with her sister Natasha (Jany Holt), a kinder woman who is being used by Vassilissa as a workhorse. Natasha ends up being pimped, virtually, to a corrupt official in charge of inspections and by intervening Pepel finds that Natasha is willing to throw in her lot with his. Unlike other poetic realist films from the time this one has a relatively upbeat ending for Pepel, although the Baron is left to cope with life and death in the flophouse.

Renoir frames his studies with an artists eyes, the settings are thoughtful and beautifully realised. He contrasts the bonhomie of the lower class with the starchiness of the middle class taking wine and tea at a parkside restaurant. The police are happy to lock Pepel up until the baron comes to vouch for him, of course the appearance of a minor aristocrat has them fawning all over him. Renoir and Gorky are scathing of this cultural conditioning, these arbitrary conventions that are without value in the real world of the ‘lower depths’, where the value of a true friend is not measured by social rank. Simple pleasures like dozing on the river bank are elevated to a sublime mystical experience once you are truly in touch with your inner self. The examination of class was a theme Renoir returned to again and again.

The political implications of the film need to be seen through the prism of the election of a short lived leftist government in France, the Front Populaire, which Renoir was an ardent supporter of. The class gap between the Baron and the Robber is defused, as there is no longer anything left to steal. They unite against a common enemy, the rapacious landlord, and in an act reminiscent of The Crime de Monsieur Lange Pepel, more or less accidentally, kills the villain on behalf of the community, an act that changes nothing for the inhabitants of the lower depths. Justice in this sense is impotent, a greater and more collective and systemic justice would be required to help balance the ledger, and one that remained frustratingly out of reach while the right wing fascists rose to power in Europe in the '30s, ending the dreams of Fronte Populaire supporters like Jean..

Renoir never stopped probing the human psyche, revealing ourselves to ourselves, his profoundly humanist viewpoint suffuses all his work and is as lasting a gift to us as the beautiful artworks his father created. This is Jean’s ‘Still-life with common people’, elegantly framed and studiously realised. Superb.