The son also rises

By Michael Roberts

"For my part, that every human creature, artist or otherwise, is largely the product of his environment. It is arrogance for us to believe in the supremacy of the individual... We do not exist through ourselves alone but through the environment that shapes us"

~ Renoir's foreword to his autobiography 'My Life and My Films'

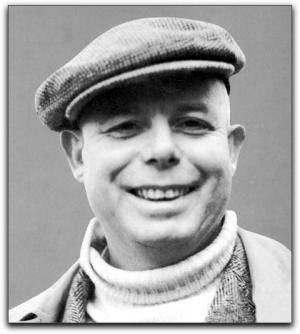

It may not be going out on much of a limb to agree with Orson Welles, John Ford and François Truffaut that Jean Renoir was the greatest film director of all time, but it's the depth and lasting impact of his films that forces me to agree with those cinematic heavyweights. Renoir was the son of Pierre-Auguste Renoir, the famous Impressionist artist and grew up in a world of culture and ideas surrounded by women, and after WWI he stumbled into filmmaking primarily in an attempt to make his then wife, Catherine Hessling, a movie star. Renoir worked in silent film, making his independent productions as an impulsive amateur, and often financing them by lifting a canvas of his father's off his wall and selling it. 1926's Nana, an adaptation of a Zola novel was his first real professional effort and announced the arrival of a significant new cinematic talent.

Renoir embraced sound in ways other great French director's like Rene Clair did not, and found a wonderful collaborator in iconic French comedian and actor Michel Simon. Their collaborative triumphs showed boldness and invention and growing mastery of the medium, as La Chienne in 1930 and Boudu Saved From Drowning in 1932 set Renoir up for one of the most fertile creative periods of his career. Renoir followed the lead of French pioneer Marcel Pagnol in exploring rural and peasant themes, evocatively shot on location, along with his Italian assistant Luchino Visconti, and he produced a forerunner to Italian Neorealism in the location filled slice of life drama Toni, (produced by Pagnol) and an early humanist hymn in the truncated and never released at the time Partie De Campagne, masterpieces both.

The politically charged atmosphere of the 1930's spurred Renoir into a more personal style of cinema, making statements of art to support his convictions during the leftist 'Front Populaire' period, and soon Renoir was making the relatively new medium his own, commanding its visual palette as convincingly as his father wielded his paints. Renoir made his comment on the power and moral responsibility of the collective in his forceful storytelling of The Crime of Monsieur Lange, made a documentary for The Communist Party and attempted to align and contrast the politics of the 1930's with Revolutionary France in his version of La Marseille.

The latterly defined genre of French Poetic Realism fitted Jean's work perfectly during the late '30's and he provided four of its immortal achievements in The Lower Depths, La Bete Humaine and La Regle de Jeu (The Rules of the Game) and his pre war hymn to humanity La Grande Illusion. If Renoir had retired at that point his place in the film pantheon would have been assured, but a combination of money, vanity and insecurity led to his leaving France for America, the land of his youthful dreams. In truth, taking into account Jean's penchant for self-mythologising, Renoir was a chameleon and his ability to accomodate and adapt led to him applying his artistry under many different and often circumstances, but he never again lived in France and felt some guilt about deserting his country in its hour of need. He was careful never to criticise the filmmakers that stayed and worked under the Nazi occupation.

The war forced a move to Hollywood, and jean embraced the chance to work and live in Los Angeles. The town was indifferent to an artist like Renoir, but he scratched a living like many emigre directors and eventually landed Swamp Water, a fine first American effort for Daryl F. Zanuck at Fox. Renoir supported many anti-Fascist causes and made This Land Is Mine, an early anti-Nazi film with his great friend Charles Laughton. His American period produced other interesting if flawed results, like The Southerner , for which he received his only Academy Award Best Director nomination and The Woman on The Beach, films that hold up much better it must be said than many of their contemporaries. He even filmed a long time cherished project, the very fine Diary Of A Chambermaid, with husband and wife team, Paulette Goddard and Burgess Meredith.

The politics of post war America were decidedly unfriendly towards left leaning humanists like Renoir, and he left to make pictures abroad before he would almost certainly have become a victim of HUAC and the blacklist. He returned to France in the '50s, re-invigorated by a side trip to India that produced the beautiful and masterful The River, and made his late colour masterpieces, films that examined the world and mores of the culture in which he grew up in. Renoir made a series of films that harked back to the artistic and theatrical roots of his youth, tributes to the Paris he knew and loved. A series of fine, colourful evocations of a bygone Paris in The Golden Coach and French Can Can as well as Elena and Her Men, a worthwhile piece with his good friend Ingrid Bergman presaged a few smaller productions that still exhibited Renoir's trademark touches of formality and deftness.

Jean continued to live in Los Angeles, despite never making another American film, and worked assiduously on stoking his own legend, aided by François Truffaut and a fawning crowd of writers at Cahier Du Cinema, all attached to the auteur theory, one that suited Jean's image of himself very nicely. Renoir's personal foibles aside, best understood via the insightful prism of Pascal Merigeau's stunning 2016 biography, his lasting legacy is to have created a body of work that is both humanistic and empathetic, focusing on the things that unite us rather than what divides us. As long as cinema endures his work will be part of its essential canon, illuminating and beguiling us with images and stories that speak deeply to every human. To quote Peter Bogdanovich, "When I despair of humanity, I watch a Renoir".

"I think Renoir is the only filmmaker who's practically infallible, who has never made a mistake on film. And I think if he never made mistakes, it's because he always found solutions based on simplicity—human solutions. He's one film director who never pretended. He never tried to have a style, and if you know his work—which is very comprehensive, since he dealt with all sorts of subjects—when you get stuck, especially as a young filmmaker, you can think of how Renoir would have handled the situation, and you generally find a solution." ~ François Truffaut

Also recommended;

Boudu Saved from Drowning

French Can Can

Swamp Water

For Fans Only;

La Marseille

Best avoided;

None that I've seen!