Hathaway delivers top floor noir, again.

By Michael Roberts

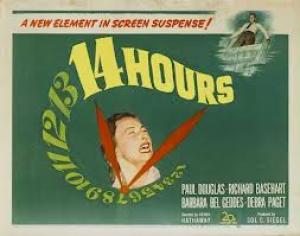

Henry Hathaway was assigned the true life drama 14 Hours, based on events in New York during 1938 and the suicide of a young man witnessed by crowds of people in the streets after an 11 hour vigil. 20th Century Fox bought the rights to a New Yorker article on the event, intending it as a vehicle for contract player Richard Widmark, and changed the names and location before offering it to Howard Hawks. Hawks was not keen on the subject and passed and Widmark was not utilised, Fox opting for a young stage trained actor called Richard Basehart for the part of the man on the ledge. Paul Douglas was cast as the decent beat cop who tries to talk him down and Barbara Bel Geddes as the girl who broke his heart. Hathaway scheduled for 3 days location filming in Downtown New York, but the location work dragged on for 2 weeks. Hathaway persevered and turned in one of the oddest and most vibrant film noir’s of the period.

Robert Cosick (Richard Basehart) walks out on to the ledge of the fifteenth floor room he’s taken at a large New York hotel. A commotion breaks out on the street as he’s spotted and Charlie (Paul Douglas), a traffic cop rushes to the ledge to try to talk him down. The two bond until the ‘experts’ arrive and Charlie is sent back to the beat, but Robert declares that it’s only Charlie he’ll talk too, and the affable cop is summoned again. The hours drag on giving cause for hope, “If they don’t jump in the 1st hour,they don’t jump”, but Robert seems determined to end his life and rebuffs attempts from his mother and father for him to come inside. The police attempt to delay him at least while they try to construct a large net they can surreptitiously deploy from the floors below.

Hathaway drives the action in a two fold strategy, with a fast paced and dynamic flow when the narrative focuses on the surrounding players and a slower pace when Robert and Charlie interact, and it’s this balance that provides the key to making a vibrant and engaging film. The many types that become glued to the unfolding drama also give up some of their own stories as the day progresses. Grace Kelly, in her first film, plays a young woman at a divorce lawyer’s office watching from a window, contemplating her own fate, the young couple who become acquainted and develop a relationship, the boy played by Jeffrey Hunter in his first film. Hathaway teases out every kind of attitude towards the man on the ledge, from the cynical taxi drivers making a book on what time Robert will jump, to the direct newspaper reporters who hope he’ll jump in time for their next edition, “They always die for the morning papers”. “Maybe he’s just lonely”, says a lonely older woman.

The film turns on the humanity represented by Charlie, beautifully played by Douglas in one of the roles of his life, an actor more used to smaller supporting parts. Basehart captures Robert’s neuroses perfectly, playing the pathos and brittleness with a nice understatement. The story spoke to post WWII America, as the country was metaphorically on the precipice of the unknown, a Cold War brewing to create uncertainty and fear, and many veterans still unable to come to terms with their (then undiagnosed) post traumatic stress conditions. Hathaway plays with the relatively new media circus idea by having the event covered on live TV, a presciently modern motif that pointed the way to the 24 hour news cycle. The direct result of that impetus is reflected in the ghoulish comment directed at Robert’s mother at a press conference, “If she gets hysterical, get a shot of it”.

Cinematographer Joe MacDonald, who’d gained distinction in many films such as Ford’s My Darling Clementine and Kazan’s Pinky, was something of a Hathaway veteran too having helmed his noir’s The Dark Corner, Call Northside 777 and The Street with No Name. MacDonald also worked on Kazan’s brilliant Panic In The Streets, as did Paul Douglas, who co-starred with Richard Widmark in that very fine medical epidemic drama. Hathaway was comfortable with the similar docu-drama aspects of 14 Hours, and MacDonald provided the superb atmosphere via a clever and cutting edge use of back projection. The tool is made unusually effective by various angles and aspect ratios that are seamlessly melded with the actual location footage, and doesn’t stand out as ‘fake’ as most back projection from the era does.

Henry Hathaway fitted the ‘journeyman’ definition of a Hollywood director, making 62 feature films over a fifty year career from 1932. Much like Raoul Walsh, he was efficient and ‘invisible’ and never won critical acclaim or Oscar nominations, the one exception being for The Lives of a Bengal Lancer in 1935. Unlike the affable Walsh, Hathaway was a widely feared disciplinarian, who stated, “To be a good director you've got to be a bastard. I'm a bastard and I know it”. Hathaway has since carved a critical reputation in the world of Film Noir, a situation that would probably mystify the taciturn director, and with 14 Hours the proof of his ability in the form is self evident. I4 Hours is a fine and worthwhile investment of your time.