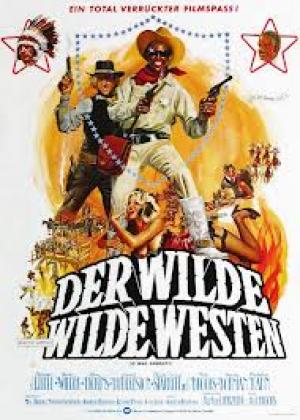

Mel toasts the west, black on both sides.

By Michael Roberts

Mel Brooks re-wrote the rules on what was acceptable comedic fare in American cinema with his boundary pushing The Producers in 1969. The film was an underground critical hit, and ran for long engagements in a few theatres but made him no money and did not result in any studios lining up to hire him. Brooks’ second film was pure highbrow ‘art house’ and soon he was newly married with a young son and literally scouring the sidewalks of New York for nickels, badly in need of work. Providentially a script arrived in the form of a comedy western and Brooks clutched at it as a parched cowboy in the desert would a water bottle. Brooks hired a team of writers to overhaul the script, including the spiky black stand up talent Richard Pryor, and Warner Brothers hired him to direct the finished product, and crucially (and remarkably) they also gave him 'final cut'.

A railroad in the Wild West is under construction and needs to be diverted because of quicksand, it will now need to go through a town called Rock Ridge. Hedley Lamarr (Harvey Korman), an unscrupulous politician, decides to cash in on the resultant real estate boom by driving out the residents before they find out about the railroad and to buy the land for himself. Lamarr has the governor appoint a sheriff so unpalatable to the town that he’s sure they will leave, that sheriff is Bart (Cleavon Little) and he’s a black man. Bart arrives in town and barely avoids being lynched before he gets friendly with the town drunk in his gaol, The Waco Kid (Gene Wilder), and together they negotiate the perils and pleasures of life in a western town. The townsfolk soon come to beg the pair for help when Lamarr hires a murderous army to destroy Rock Ridge.

The narrative takes a back seat to the disparate, episodic and riotous comic sequences that form the basis of the film. Little’s cool urbanite completely flummoxed the redneck hicks of Rock Ridge, from his Gucci saddlebag to his cool rendition of Cole Porter’s I Get a Kick Out of You, giving Brooks to send up the western simpletons and their "authentic frontier gibberish". Brooks says the biggest laugh he got in the hastily convened screening that saved the film from oblivion was after Gene Wilder’s admonishment to Bart to not judge the townsfolk too harshly, calling them “just simple farmers, people of the land, the common clay of the west, you know…. morons”. The comedic anarchy results from the constant inversions of expectations and overturning of well used western clichés, including a brilliant Madeleine Khan impersonation of Marlene Dietrich in her iconic western role of Frenchy in Destry Rides Again. Another sacred cowboy name is intoned with an angelic choir rejoinder when Bart asks for time to come up with a plan, “You’d do it for Randolph Scott”!

Brooks uses the same trope he unearthed in The Producers, the conceit of setting up something to fail, a musical based on the Third Reich in the first film, and the appointment of a black sheriff in Blazing Saddles. Both choices were designed to offend, to push the boundaries and challenge perceptions and prejudices, and to create a ‘designed’ failure. Brooks also delights in sending up and deconstructing movies themselves, from Waco’s declaration “I must have killed more men than Cecil B. DeMille”, to the fourth wall breaking finale where the extras in the western bar brawl crash through to a Busby Berkely style musical set where Buddy Bizarre (Dom DeLuise) is directing a dance number. Brooks even turns the joke back in on itself by having LaMarr walk into a modern movie theatre that is playing Blazing Saddles! In this post modernist swirl Brooks manages to insert Nazi’s (of course), The KKK, Loonies Tunes, Arabs on camels and Count Basie and his full band playing April in Paris.

The outline is no more than a starting point for the broad and anarchic humour that Brooks produces, one with deeper social resonances given the underlying, satirical look at racism. The initial screenplay was titled Tex X, an allusion to Malcolm X, but Brooks was told to find a less ‘political’ title. Brooks had wanted to cast Richard Pryor as Bart, but Warner Brothers vetoed the choice, not wanting to take a chance on the drug fuelled comic. Brooks found the Broadway trained and talented Cleavon Little instead and started filming the script as written, getting the blessing of both Pryor and Little over the controversial use of the ‘N’ word. Slim Pickens and a host of stock western actors add a level of authenticity that makes the satire even more effective. From the Bonanza burning logo to the Frakie Laine voiced theme, no sacred western cow remained unslaughtered.

Brooks wanted an older actor for the Waco Kid and initially approached aging song and dance man Dan Bailly, but he was losing his eyesight and couldn’t take the risk. Brooks then cast Gig Young in the role of the alcoholic, reasoning that Young’s actual alcoholism would add to the performance, but after Young was taken away by an ambulance on the first day’s shooting production stopped. Gene Wilder was a close friend of Brooks’, having starred in his first film, (The Producers) and had expressed interest in the part, but Brooks thought him too young. Wilder took the first plane to Los Angeles at Brooks’ request and filming re-commenced, Wilder was already across the script and only half a days shooting was lost. It’s unimaginable to think of anyone else as Waco, so definitive and effective was Wilder’s star making turn as the sweet natured gunman.

Warners insisted on Brooks cutting any trace of the word ‘nigger’, the infamous ‘horse punch’ and the campfire farting scene, but Brooks held to his final cut clause and kept the offending scenes in. The only line (and a zinger) he cut was Bart to Lily in the dark room, “I hate to disappoint you baby, but that’s my arm you’re sucking on”. Warners reckoned the film could only play in a couple of urbane major cities like New York and Chicago, that the south was out of the question and considered whether to “eat it”, industry jargon for taking the production cost of $2.6 million as a loss and not releasing the film at all. Brooks won the day with a packed room screening of people apoplectic with laughter who raved about the film to the company execs.

Thankfully the film then squeaked past the nervous nellies at Warners and was given a release, one that did so well it enabled the film to even have a re-release 6 months later, and to be one of the most profitable films in Warners history. Brooks finally had enough clout to enjoy a significant career as a filmmaker, and with his company Brooksfilm he made not only comedies but produced splendid serious fare like The Elephant Man and Cronenberg’s The Fly. One of Wilder’s stipulations for extracting his friend Brooks from the shit after Gig Young’s abrupt exit was for Brooks to agree to produce an idea of Wilder’s involving a comic re-make of Frankenstein. Young Frankenstein was to be their next film, another huge smash hit and perhaps Brook’s best film.

Blazing Saddles appeared just as the major feature western was riding off into the sunset, after being a mainstay of American cinema for almost 75 years. The comedy is broad and it opened the way for the modern ‘gross out’ style of shock comedy, possibly not a good thing, where nothing is too much and going over the top is the order of the day. Blazing Saddles now seems positively restrained by comparison, but it is superior fare, a reminder that wit is an essential ingredient in making comedy work, no matter how broad, and a good director is a bonus. Not everyone gets it…. certainly not actress Hedy Lamar, who sued Brooks over the use of her name! That’s showbiz!

(sing) “He rode a blazing saddle”…