Lang's role reversal

By Michael Roberts

"I was called the greatest director in Europe, but I was just a hard worker."

~ Fritz lang

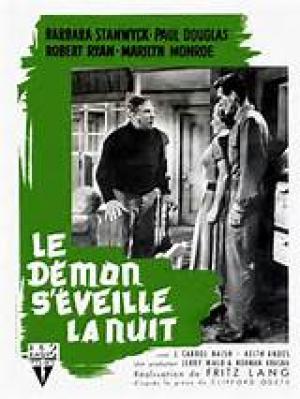

After getting a second chance in Hollywood in 1935, the Austro-German director Fritz Lang set the tone for an entire genre (Film Noir) the next year with his proto-Noir , You Only Live Once. Lang then quietly busied himself by creating a body of work in American films that continues to fly under the radar of the cognoscenti as he helped to delineate the boundaries of much of the best cinema of the era. The horror of having to flee the Nazi’s in the 30’s and of the dark crimes of the German’s in the 40’s would never be far from his émigré thoughts, and his work took on a special power when it dealt with the seedy side of humanity, as in Clifford Odet’s drama Clash by Night. In this stylish Noir piece from his late career he gave the inimitable Barbara Stanwyck one of her best roles and also gave the young Marilyn Monroe a sympathetic support role that hinted at the glories to come. The mighty RKO produced the film, after Howard Hughes had almost ruined the studio, and talented Val Lewton Unit veterans, Nick Musuraca and Roy Webb provided the excellent cinematography and vivid musical score respectively.

Lang opens with the roiling sea, a metaphor for the churning emotions that lurk beneath some of the residents of the sleepy fishing port near Monterey. In contrast, Jerry (Paul Douglas) is seen as a commanding captain in charge on a calm stretch of water as he brings his daily catch into the harbour. Marilyn Monroe wipes the sleep from her eyes and drags herself out of bed to start the day at a mindless process worker’s job on Cannery Row, while Jerry bumps into returning resident and sister of Peggy’s boyfriend, Mae (Barbara Stanwyck) in a bar. Soon Jerry is dating Mae, introducing him to his knockabout friend, the misogynist Earl (Robert Ryan) as Peggy who is feeling claustrophobic in the small town and envious of Mae’s adventures, looks to the older woman for guidance.

Some cineastes don’t regard Clash By Night as a true Film Noir, give its antecedents in the neo-realism of Odets play, but I think it is - more than that I think Lang was pushing the boundaries of the form by subtly subverting it under our very noses. The concept of the femme fatale is central to Noir and one of its strongest motifs, yet here the femme fatale character is not Mae, it’s Earl, something that can’t have escaped Lang’s eagle eye. Mae is one hard-boiled broad firmly in the tradition of the best Noir, like Jane Greer in Tourneur’s Out of the Past, or Stanwyck’s own immortal Phyllis Dietrichson in Double Indemnity from maestro Billy Wilder, but she is not a classic femme fatale. Mae does not fill the usual role of the temptress in Noir, luring the steady, sane man away from the rational choice – here she has chosen the safe option, marrying the ‘ordinary’ guy and knowing it goes against her wilder nature, and it’s Earl who appears as the ‘temptress’ luring Mae away from family life.

Clash by Night, like many a Film Noir, is a film about carnality in an era when sex could not be directly addressed in mainstream cinema. Lang knew casting would be pivotal and all the leads prove to be exceptional fits for their roles here, well able to suggest sexual tension. Barbara Stanwyck provided one of the finest late career characterisations in Mae, a brooding mess of frustration, coming home to a small town with her tail between her legs after her dreams of big town success came to naught, “expect nothing, hope for nothing”. Stanwyck spits out some killer lines, asked what she needs by Earl, with Jerry next to her, she replies, “Let’s say a drink”, and Ryan matches her with his bleakness, “You’re like me, you’re born, you want to get unborn”. Lang frames the emotions that boil within Mae with cutaways to the endlessly turbulent ocean, as she vainly attempts to tame her own nature, but she gives away her carnality with the subtlest of gestures, squeezing her hand under Earl’s singlet as the desperately embrace and kiss for the first time. Mae also recognises Earl’s attraction to the younger woman, and desperately hangs on to her fading sexual allure by giving in to Earl’s advances.

Counterpoint to Mae’s worldly cynicism is the wide eyed hopefulness of Peggy, beautifully realised by Marilyn Monroe in an effortlessly charming portrayal. Fox recognised her star quality and soon elevated her to the first rank with starring roles in Howard Hawk’s MonkeyBusiness and Henry Hathaway’s Niagra. It’s Peggy who lives out the late dawning realisation that Mae gives voice to, “Ya gotta trust somebody, there ain’t no other way”. The under-rated Robert Ryan gives his usual note perfect characterisation of the blackguard Earl, reprising his role in the original Broadway production a decade earlier, his dark good looks perfectly suiting the many villainous roles he excelled in, ironic given his personal placidity and gentle nature. Paul Douglas is somewhat stagey as Jerry, but does enough in the key moments to balance the male equation.

Odets was a champion of the left in the mid 30’s, involved in New York’s Group Theatre with close friends like Lee Strasberg, Elia Kazan and Harold Clurman, scoring a huge hit with the play Waiting for Lefty. He again scored hugely with the follow up production Awake and Sing! In 1936 and was one of Broadway’s young lions after the hit Golden Boy in 1939, with the source play for this film, Clash By Night, coming in 1941. His brief membership of the Communist Party came back to haunt him just prior to the film versions release, and he testified before HUAC, agreeing with his friend Kazan that both would name each other to the committee, reasoning that as the committee already had both their names no harm would be done and they’d be seen as co-operative witnesses. The move backfired for Odets, much more sensitive than the rhinoceros hide of Kazan, who was judged by his leftist friends as having named names and struggled with the fallout until his death from stomach cancer a decade later. The film version saw Odets past his glory days as a playwright, although he would later enjoy some high regard in relation to his work on the screenplay of Sweet Smell of Success, one of the definitive Film Noir’s of the time. Lang, no political animal himself, suffered from 'guilt by association', and struggled to get consistent work through this period, as one of the many artists 'greylisted' by the studios.

Fritz Lang went about his business in Hollywood for 20 years as a solid, jobbing director, with few appreciating his stature as one of the pivotal directors in the history of cinema. He ploughed on regardless, making a fine and coherent body of work in America that has eventually been recognised as a superb legacy in its own right. Lang’s taste for reinvention and subversion was broadly missed at the time, but in 1952, before he made Clash by Night, he’d made the offbeat western Rancho Notorious, with Marlene Dietrich subverting the usual sexual roles in that film in the same way Stanwyck does in this. Lang was working in the mainstream in plain sight, but also perfecting a direct and spare visual style with a philosophical underpinning that cut to the heart of the matter, to the turmoil and restlessness that beats below the surface, to the darkness in the human soul.