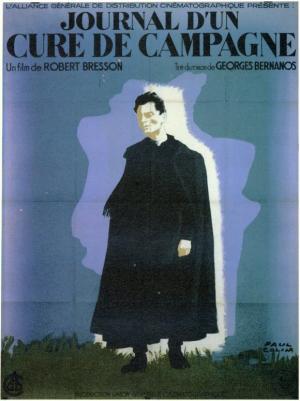

Act of faith

By Michael Roberts

"Don't run after poetry. It penetrates unaided through the cracks" - Robert Bresson

Robert Bresson changed artistic tack after his elaborate Les dames du Bois de Boulogne, seemingly taking the lead from Jean Pierre Melville's austere and minimilist Le Silence de la Mer... Melville certainly thought so! Either way, Bresson was such a gifted artist that he took the idea of minimalism and proceeded to take it as far as he could with his subsequent visual tone poems, of which Diary of a Country Priest is the first. The wintery visual tones anticipate the great Bergman films on faith by at least a decade, and Bresson's works stand up with the existentialist masters in every way, and given Bresson described himself as a "Christian atheist" they also shared unbelief in a supernatural explanation for the nature of the universe. This is not to deny both men were seeking to understand the poetic nature and yearning for transcendence that beats within the human heart, they rightly understood that the search is not disqualified by non belief. As Bresson well knew, even highly placed churchmen are unbelievers.

The Diary of a Country Priest is a beautiful film, layered and nuanced and delicate. Bresson’s country priest is hanging on by the quill of his pen, it’s as if making his mark on a page is the only way he can validate himself or leave some kind of indication that he was alive at all. Based on a pre war novel, the story unfolds of a modest young cleric taking his post in a small rural community, and from the opening sequence it’s made apparent that he is an outsider or worse, an intruder. The shy priest unwittingly observes an illicit liaison, the repercussions of which he can not know will shake the small town to the core. The deliberately beatific Claude Laydu plays the title role, and Bresson insisted on a practicing believer in the role, one assumes in the hope of a achieving a kind of verisimilitude in the scenes where a ‘rapture’ of sorts is required. The young priests tools with which he has to deal with the reality he encounters prove to be singularly inadequate and he turns for advice to an older priest in a neighbouring parish. The battle is between weary pragmatism, represented by a Doctor and by the older priest and the idealism and ethereal notions of the young priest.

The day to day ennui of a country town gives the priest plenty of time to contemplate eternity. His is a lonely and spartan life, which serves to accentuates the contact he does have with other characters. Events that would be of little consequence normally take on a wider significance because most of the things humans take for granted in a social context are denied him. The divide between what he aspires to for the human heart and the reality of what it does is a troubling one for him, so he falls deeper into his spiritual trance, only to be awoken with a start when circumstances come breaking through. Almost as a physical manifestation of this inner turmoil the young priest starts to exhibit signs of serious illness. His diet is inadequate to sustain him bodily, and maybe Bresson is making the point therefore his spiritual sustenance is also not enough for a man to live effectively when he’s so removed from the real world.

The weight of the film falls upon Ladyu’s shoulders, he’s in virtually every scene and carries it off beautifully, it’s a great piece of casting. The look of the film, sombre and spare, set the tone for Bresson's work for years to come, as with the pacing and tone. Like most Frenchmen Bresson was raised Catholic, and remained interested in transcendent experiences that can be read from an existentialist viewpoint also, he seemed to be suggesting they need not be the sole province of the religious. The Priests god, as with Bergman's, was a silent one and when all was said and done the Priest was left alone. His 'community' was a celestial one, and so proved of no use to him here. The doctor had no faith in an afterlife, and so looked after the community he lived with in order to find meaning. It’s the human dilemma, we are alone, but we are alone together.

Bresson continued on his journey into an even more stripped back aesthetic with the astonishing A Man Escaped and Pickpocket, where he refined his idea's about cinema. Bresson forced his actors to become 'models', and if possible he favoured the Neo-realist device of employing non actors where he could. He would then demand his models strip their performance of any artificiality, to create a 'neutral' performance, one where the audience would fill in the blanks. Bresson became a darling of the Nouvelle Vague, a true auteur who perfectly fitted Andre Bazin's maxim, that "Realism in art can only be achieved through one way, artifice".