Early MAGA man emerges

By Michael J. Roberts

"Nobody is a villain in their own story. We're all the heroes of our own stories."

~ George R. R. Martin

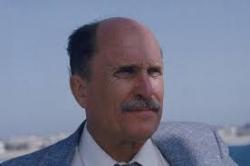

In light of the 2012 American election that saw the 'white' voting bloc fall into the low 70s as a percentage of the voting public, and the subsequent lurch to the far right with MAGA, it's timely to re-visit one of the earlier manifestations of the 'angry white male' struggling with his countries changing demographic. Michael Douglas gives one of his best performances as 'D-Fens', a man who has gone over the edge and seemingly just wants to 'go home', but encounters many obstacles in the way. Douglas is counterbalanced by the decent cop figure as rendered by veteran Robert Duvall, an L.A policeman who in his own way is adapting to keep up with a changing world. Joel Schumacher doesn't take sides in the telling of the tale, keeping some ambiguity in both male lead characters and underscoring how difficult it is to hold to a 'black and white' opinion in a world of grey.

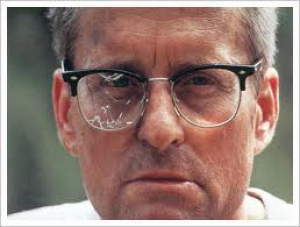

D-Fens (Michael Douglas) is stuck in L.A traffic gridlock on a very hot summers day and going nowhere. In a society based on rampant consumerism he is bombarded by endless appeals to his attention and his wallet, billboards selling something, bumper stickers doing the same from financial advice to Jesus. Reminders of his insignificance are all around him as he sees arguments and unrest build in the impotent vehicles. D-Fens takes matters into his own hands and gets out of his car and walks away, telling a bewildered fellow motorist he's "going home". Sergeant Prendergast (Robert Duvall) is on his way to his last day at work before retiring and notices the abandoned car and the personalised 'D-Fens' number plate. D-Fens calls a woman who is clearly the mother of his daughter Adele, as it's Adele's birthday and he wants to see her. The woman, Beth (Barbara Hershey) is his ex-wife and has a restraining order out on D-Fens and tells him he can't come, but he says he's coming anyway. D-Fens then walks across L.A to Venice where his former home was to wish his daughter happy birthday, but encounters the changing face of L.A's culture is the process and this uncovers all the frustrations and tensions that have been building up in his life.

Schumacher presents D-Fens as a worker drone gone wrong, in many ways he's a cousin to Burt Lancaster's Ned in The Swimmer, where a man is 'swimming' home across the pools of his suburban neighbours, and the mental torment and damage is incrementally revealed the closer he gets to his destination. D-Fens has a severe look, a cut back to basics office worker appearance, a man who is used to conforming, and says of his own life in a bewildered tone, "I did everything they told me too?" when it starts to spiral out of control. He sees a world that rewards a plastic surgeon with a lifestyle he can only dream of, whereas his career spent in support of his country and its principals via his work in the defence industry is not valued by comparison, "I'm obsolete", he laments. At the denouement he realises "They lied to me", and Prendergast replies "They lied to everyone". In an uncomprehending tone D-Fens utters the defining line of the film, "I'm the bad guy"?, as if his lifetime of an heroic 'John Wayne' type self image has evaporated in an instant. In this he speaks for a certain middle class white American demographic that likes to bemoan how it's natural inheritance is being lost in a flood of immigration and change.

The L.A that D-Fens comes into contact with is a messy and vibrant one, full of chaos and life and people struggling to make a living in a difficult environment. Rather than focus on how this situation has come to happen by a succession of institutional policy failures or entrenched corruption in those same institutions D-Fens makes the classic mistake most reactionary conservatives make and blames the victim. Ironically he's just as much a victim of the system as they are, only he doesn't realise it. The Korean shop owner should be congratulated for running a small business but D-Fens simply reacts to his less than perfect English speech and let's his frustrations boil over. Equally he's confused when a clearly deranged neo-Nazi (Frederic Forrest) helps him as he identifies with his struggle and D-Fens is appalled with the racism he's spouting, unable to see it as the logical extension of his own racist thoughts.

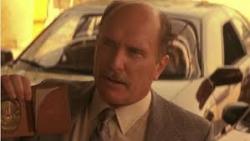

Prendergast connects the dots in an institution that views him as 'obsolete' too. He's seen as a desk jockey cop, not a real cop as he's no longer in the line of fire, having taken the safer option to calm his neurotic wife after their young daughter inexplicably died. He is held up as an example of a reasonable man working with the changing community, seeing good and bad on both sides but getting on with the business of living. Prendergast knows that D-Fens is a basically decent man who's lost his ability to cope, and with help this phase can be worked through. "You're sick" says Beth, "Take a walk around this town, that's sick" D-Fens replies, again blaming the victims in an obvious and cheap shot. The challenge is to get beyond this superficial and narcissistic judgement of the problem, and the character of Prendergast and his ability to assimilate change holds out some hope that a multicultural future is attainable and desirable.

The film works so well because Douglas' characterisation is so well informed, both subtle and strong, giving this 'villain' a humanity and depth. He works the role superbly, ramping it up when needed with a nice sardonic bite but tender as well, the scene where he meets his daughter is very fine acting, "How'd you get so big?", he asks her, and we can see a damaged man that could be redeemed. Kirk Douglas had advised his son to "play a prick" sometime and break away from his good guy roles, and he was thrilled with the result too by all reports. Duvall is as always very good in the thankless role of the stoic cop, and gives the right amount of weight to a role of a man who understands life is rarely a series of neat propositions.

Falling Down presents no easy solutions to a difficult and multi-layered topic, the creeping disenfranchisement of the privileged classes, it examines prejudice and racism, expectations and outcomes and does so with a keen and unfussy eye. The film makes some resonant points regarding what happens when consuming in and of itself runs the game, where 'consume and be silent' is the mantra for the new corporatocracy, ahead of any negative sociological impacts. Joel Schumacher has had the occasional high spot in a varied and mostly interesting career as a director, and with Falling Down in 1993 he delivered a prescient and insightful exploration of the hollowness at the heart of the American dream.