Hitch's plea to US isolationists

By Michael Roberts

'To make a great film you need three things - the script, the script and the script.' ~ Alfred Hitchcock

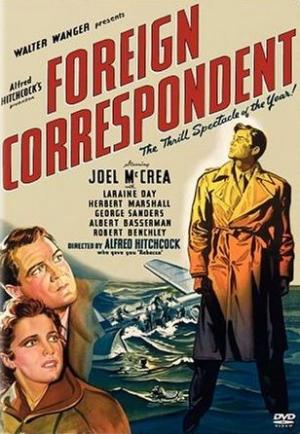

It’s been said in jest that war was ’God’s way of teaching Americans geography’, never a truer word possibly, but no excuse for WW2 as Europe at least is hard to miss. In mid-1940 Britain was under threat of assault from Hitler’s bombs and France about to fall in six weeks, America was in the grip of an isolationist policy and Neutrality Act that effectively meant that they were profiting from the war financially while making it a criminal offence for ex-pat Brits to even meet in groups in Hollywood and agitate for the end to the policy. Roosevelt openly defied the Act a month after this film was released in 1940 and had been privately working out ways to support Britain and France, but in the dark days before America decided to lend a hand Europe was at the mercy of Hitler’s jackboots and this was Hitchcock’s not-so-subtle reminder to the American public of what was happening on the other side of the Atlantic.

The film opens in the offices of a large New York newspaper, the editor is getting news from Europe that there’s ‘no chance of war’, but he’s experienced enough to know a PR piece when he sees it and knows his Foreign Correspondent is not up to the job, ’there’s a crime going on in Europe and I need a crime reporter’. He summons Johnny Jones (Joel McCrea), an action reporter and currently in the dog-house for some misdemeanour, and asks him about the crisis in Europe, ‘what crisis?' comes the reply and Jones has the job. Hitchcock wants to make plain that the average American had no idea as to what was really going on in Europe and Jones is to receive an education on behalf of them all. Hitler is mentioned for the only time in the film at this point, as Jones naively says he should interview him, ‘he must have something on his mind’? Jones’ first assignment is to get some background on a peace treaty being put together by several parties, prominent diplomat Van Meer (Albert Bassermann) and a noted pacifist Fisher (Herbert Marshall) amongst them, that is said to contain a secret clause much sought after by ‘enemy’ spies. Jones accidentally meets Van Meer on the way to a dinner but Van Meer gives away nothing. Jone’s meets Fisher’s daughter Carol (Laraine Day) at the event and is instantly smitten. Fisher makes the odd announcement that Van Meer can’t attend, and as he’d traveled to the Savoy venue with him Jones is surprised. Jones travels to Holland to another conference and meets Van Meer on the steps, only to see him shot by an assassin. Jones pursues the gunman and teams up with Carol and her Brit reporter friend Ffolliet (George Sanders) and they chase the car into the countryside only to have it disappear amidst some windmills.

Jones finds himself up to his ears in a nest of spies and realises that the Van Meer that was killed was a double to allow the spies, who have kidnapped the real Van Meer, time to interrogate him for the secret clause (Hitch’s standby McGuffin). Carol falls in love with Jones as they get deeper into the conspiracy, and in telling her father of their position Jones meets one of the spies who was holding Van Meer. Jones privately tells Fisher’s of the man’s true purpose, not realising Fisher is involved in the conspiracy. Fisher organises a ‘hit’ on Jones, by possibly the friendliest hitman in film history Rowley (Edmund Gwenn) who poses as a bodyguard protecting Jones, only to come to grief in a signature Hitchcock piece. Carol doesn’t know of her father’s betrayal until Ffolliet comes up with a scheme to reveal it, Jones and ffolliet end up crashing in on Van Meer’s interrogation and pursue Fisher who is flying to America with his daughter, who by now has fallen out with Jones over a misunderstanding. Fisher confesses and the plane is attacked and crashes, the survivors clinging to the wreckage. Fisher, having admitted his guilt, swims off to certain death. Jone’s goes back to London, now under bomb attack and during an air-raid while he’s broadcasting to America he makes his stirring speech encouraging America to not let the lights of freedom go out.

Producer Walter Wanger had this script in work for years, originally centred on the Spanish Civil War, and many writers had a hand at it before Hitchcock re-focussed it on the trouble in Europe. In keeping with a familiar maxim Hitch made the villain suave and charismatic, reminding us that true evil need not be gross exaggeration, it can sometimes be banal and subversive, and Marshall makes a great fist of the part, convincing us in his misguided endeavours of ‘fighting for his country’, eulogising those ‘unscrupulous, mad and inspired’ patriots that will stop at nothing to gain advantage over complacent or unengaged adversaries. Even Fischer’s daughter was in the dark as to the extent of her Father’s involvement, evil can flourish very close to home. McCrea plays the part with dogged determination, giving Jones an everyman-ish decency that would also be Hitchcock’s stock-in-trade for many future films with Jimmy Stewart, and Hitch makes the film play like a detective story to wash down the ‘message’, indeed Jones is even in the standard trench-coat of the Private Eye for much of the action. The Van Meer character makes the most heartfelt plea for helping ‘the poor suffering world’, and given the rise of Fascism in Europe Hitch’s humourous aside of ‘HOT’ in a set piece involving a neon sign seemed apt. The brilliant high-angle massed umbrella scene in Holland is still breathtaking, as is the plane crash sequence, a stunning technical achievement for the time.

Hitchcock had filmed an ending where Ffolliet waxed lyrical on how Germany would cover up the events, but Hitch visited London at the end of May after filming had wrapped and was told bombing was imminent, he returned to Hollywood and had Ben Hecht write the broadcast ending of bombs falling while Jones speaks to America. They filmed the scene on July 5 and the first bombs hit London on July 10. America entered the armed struggle against Hitler some one and half years later, London was largely rubble by then and France was occupied, and it took a Japanese sneak attack to force America’s hand. Given the mileage Hollywood has made from stock Nazi villains in the time since, it seems ironic to reflect on it’s reluctance to help. Hitchcock can be forgiven for handing out a history lesson and cry for help with the only tools at his disposal, he never forgot he was a Londoner, and he loved London Town.