Freudian theatre of the west

By Michael Roberts

“Anyone who rejects it should never go to see movies again. These people will never recognise… a good film, or even cinema itself”

- François Truffaut on Johnny Guitar

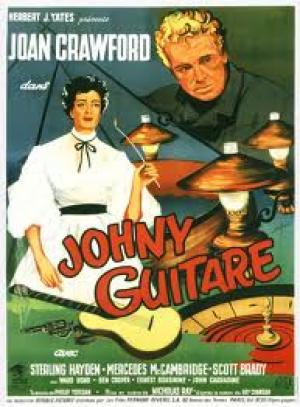

Nicholas Ray’s 1954 western is in many ways the strangest genre film Hollywood ever produced, a surreal and unsettling subversion of a western and a clear criticism of McCarthyism during the period of the blacklist. Classic era Hollywood diva Joan Crawford, well past her prime and nearly 50 years old, had moved on from the big studios and after having a Paramount project fall through she took Johnny Guitar to Herb Yates at Republic, as she owned the film rights to the novel. Crawford insisted on director Nicholas Ray to helm the project and wanted Barbara Stanwyck or Bette Davis to play Emma, but both proved too expensive for the low budget studio.

Vienna (Joan Crawford) runs a saloon on the outskirts of a mining town and waits for the railway to pass through in order to make her fortune. Johnny Guitar (Sterling Hayden) comes into the saloon and it becomes clear he’s an old love of Vienna’s, but he becomes entangled in an attempt by the locals to run Vienna out of town. Emma (Mercedes McCambridge) heads the campaign against Vienna, out of jealousy over the Dancin’ Kid (Scott Brady), a gun hand who is in love with Vienna. The townsfolk give Vienna an ultimatum to clear out within 24 hours, and Johnny’s past, and his true identity, comes back to haunt him.

Ray takes a wrecking ball to every convention associated with the western in the mid ‘50’s, taking an almost perverse delight in integrating elements of opera, surrealism and Freudian psychology. The so called ‘psychological’ western had made its appearance a few years earlier with fine pieces like The Furies and The Naked Spur from Anthony Mann and even Raoul Walsh chimed in with Pursued. Ray pushed the envelope further than anyone had attempted, creating a nightmarish dream-west for his characters to inhabit. The colour pallete used by Ray’s cinematographer, veteran Harry Stradling, further underscored the madness at the core of the film, bringing out an earthy beauty in the frontier landscape. Stradling had already proved himself a master in black and white cinema with Hitchcock’s Suspicion and the superb noir shades of Kazan’s A Streetcar Named Desire and Preminger’s Angel Face, and would go on to win the Academy Award for the colour film My Fair Lady.

Even if there were strong female characters in westerns prior to Johnny Guitar, like Barbara Stanwyck in The Furies and Marlene Dietrich in Lang’s Rancho Notorious, Joan Crawford’s Vienna and McCambridge’s Emma are unparalleled when taken together. “I never seen a woman more like a man”, is the jarring assessment of Vienna by one of her staff, and unsettlingly delivered straight to camera. The deliberate disorienting of sexual identity in the main characters is amongst the most deconstructionist in all of cinema, the feminine are masculine and vice versa, leading to the iconic shootout between the two women. Ray frames Vienna in bridal white at one point, playing piano and lighting candles for her newly reclaimed lover, before she is forced back into denim jeans to take care of business. McCambridge is dressed in black, the lead avenging angel in the best attired posse in history, and when the men refuse to hang a woman Emma gladly steps up and shows them how.

The tension between the two women was exacerbated by the real life enmity they felt towards each other, aided and abetted by the fact that Crawford was having an affair with the director during the filming. Both women were having problems with alcohol at the time too, and Sterling Hayden went on record to say he hoped never to work with Crawford again, “There’s not enough money in Hollywood to lure me into making another film with Joan Crawford. And I like money”. McCambridge was succinct, she called Crawford a, “Mean, tipsy, powerful rotten egg”.

The screenplay was for Johnny Guitar was credited solely to Philip Yordan, a notorious front man and supreme networking operator at the time, who took advantage of the blacklist embargo on other writers to benefit personally. It is widely thought that the enigmatic leftist Ben Maddow contributed heavily to the work, and it makes sense when you read the anti-HUAC subtext. Maddow had been blacklisted after his acclaimed work on Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle, and eventually he recanted and ‘named names’ in order to work under his own name again. A scene where Johnny reclaims his real name of Logan resonates with the idea of Johnny, like Maddow, not hiding behind a pseudonym any longer. Fellow blacklisted writer Walter Bernstein wrote of his colleague after he’d become a ‘friendly’ witness, "it had nothing to do with money or politics or being afraid or not able to work. He simply could no longer stand living in the shadows. Something had broken in him."

The HUAC subtext is further reinforced by the scenes where the leaders of the posse force their views on the townsfolk. Ironically Ray has notorious anti-communist and red baiter Ward Bond mouth the ultimatum to tell Vienna and her crew to get out of town, only to have Johnny respond, “He can’t make up his own laws”! Bond was a driving force behind the fascist organisation the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals, which ran a blacklist of it’s own, a list it obligingly provided to HUAC. Emma gives the most overt soliloquy, passionately urging the posse on to becoming a lynch mob, “You better wake up or you’re gonna find you, your women and your children squeezed between barbed wire and fence posts”. Vienna challenges their authority when they do come to lynch her, as many did with HUAC, “Who are you, with your angry faces and evil minds”?

Sterling Hayden may have given Ward Bond a wide berth during filming, as Hayden reluctantly became a friendly witness, ‘naming names’ to HUAC in order to continue working. He had a low opinion of the acting profession to start with, and was a bona fide war hero, winning the Silver Star as an OSS agent during WWII, and he also had ambitions to be a writer. He fell into a pit of self-loathing after HUAC, writing in his autobiography, "I don't think you have the foggiest notion of the contempt I have had for myself since the day I did that thing”.

Johnny Guitar was ignored in America but both the film and Nicholas Ray were lionised in France by the critics of Cahier Du Cinema, particularly the pair who were to become A-list directors themselves within a few years, François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard. It remains the strangest western to come out of mainstream cinema, a fact made even more remarkable in that it spewed from the white bread world of the Eisenhower years. Nicholas Ray was soon to go on to the unambiguous triumph of Rebel Without a Cause, but Johnny Guitar is a ‘once seen never forgotten’ one of a kind.