A letter to Goebbels

By Michael Roberts

“Some artists smuggle messages in their work”

- Bertolt Brecht

In Le Corbeau Henri-George Clouzot produced one of the most misunderstood films of all time. France was under German occupation and all films had to be approved by the ruling Nazi party apparatchiks, or the Vichy Government in the southern 'free' zone. Jews were blacklisted and, as happened in Hollywood years later, some continued to work under assumed names. The entire atmosphere of the times was one of suspicion and paranoia and with collaboration, as with everything else there were degrees, and so the final film would result in a disputation as to the ‘degree of collaboration’ it represented. The Nazi’s used Le Corbeau as anti-French propaganda in Germany, maintaining that the French were weak and selling each other out. Of course a clearer reading of its intent would be that it condemns a regime that provides such an atmosphere where neighbour turns upon neighbour, and that betrayal of country to such a regime as the Nazi's is the ultimate collaboration.

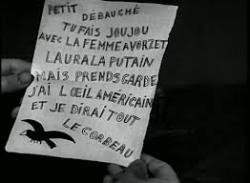

Doctor Germain (Pierre Fresnay) is the target of poison pen letters accusing him of having an affair with a respected colleague’s wife and of being an abortionist. Germain attempts to discover the identity of The Raven in order to clear his own name, and uncovers more secrets and dark desires in the process, both in others and in himself. Germain examines a series of suspects as more letters rain down on the town, creating chaos and destruction in their wake. Germain’s already shaky opinion of humanity is further shaken, as the caustic older colleague Dr Vorzet (Pierre Larquey) taunts him, “You think people are all good or all bad”? Vorzet knows the dividing line is a moveable feast dependent upon many external and internal inputs.

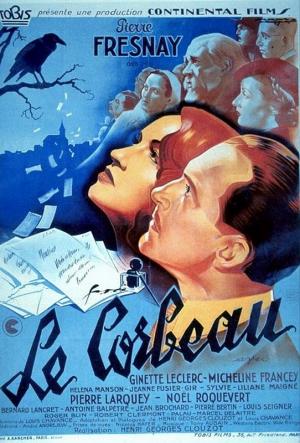

Clouzot’s almost maniacally meticulous working method caused problems on the set with his lead actor, Pierre Fresnay, and the previously close pair fell out. Fresnay had starred in L'Assassin habite au 21, the slick escapist fare that Clouzot made as his first directing effort, and although Clouzot could be a violent and explosive character Fresnay avoided his temper through the first film, but not so on Le Corbeau. Fresnay had ironically promoted Clouzot in the late ‘30’s as a talent, befriending him after a period of illness, when Clouzot had spent 4 years in a sanitorium suffering from tuberculosis. Fresnay was imprisoned for 6 weeks after the war for working on Le Corbeau, as was the leading actress Ginette Leclerc.

The Germans, via Joseph Goebbels, set up a company to control French output, and banned all films by the Allies, so the vacuum meant a lot of production needed to be undertaken to fill the countries screens. The German film industries reputation had suffered since Hitler's rise to power and its reduction to propaganda wing of the party, and the head of the new company, Dr Alfred Greven, actually wanted the French industry to avoid the same fate. He modelled his running of the company, Continental Films, along the lines of the Hollywood moguls whom he envied. After Clouzot had established his credentials with a couple of writing jobs for Continental, and a successful debut as director with L'Assassin habite au 21, Greven gave him free reign with Le Corbeau, and lived to regret it. Clouzot based the film upon an actual incident in the provincial town of Tulle in the pre-war era and the mystery and destabilisation that a series of anonymous poison pen letters caused there. Clouzot built an atmosphere of mistrust and suspicion, showing exactly how oppressive regimes undermine the bedrock of civil societies.

Clouzot was hauled before an anti-collaborationist tribunal after the war in regard to Le Corbeau, and he had this to say; "I'll tell you exactly why I made it. I was fed up with the terrifying climate of denunciation in which we lived, with all the anonymous letters. I should say that Bauermeister, who was head of production, thought it was too harsh and disturbing a subject. So I had to fight with Greven, who told me it was a very dangerous film, but I was determined to make it. It was a revolutionary film that fascinated me. In the end he said 'Ok, be it on your own head, make it".

Greven ran foul of his bosses with films like Le Corbeau, and Goebbels later wrote, "What the French need are frivolous films, empty, even a little stupid, and it's our job to see they get them. It's not our job to develop their nationalism". The Gestapo ordered the company to halt the promotion of the film that featured the slogan, 'The shame of the century, anonymous letters!' because they thought it would undermine its steady supply of collaborationist informers. The Gestapo could not believe how readily the French were informing on each other, and wanted nothing to compromise that state of affairs.

Clouzot, (before Claude Chabrol appropriated the title) was known as a French Hitchcock, and that reputation existed, based on later masterpieces like Les Diaboliques and The Wages of Fear (Le Salaire De La Peur). Le Corbeau is a marvel of visual economy, spare and razor sharp, worthy of a Bresson, and typical of the poetry and restraint of the best French directors (think Becker’s Le Trou). The premise is intriguing and serves to keep the audience as well as the characters guessing which way events will unfold. There’s a thriller element overlay on what is essentially a morality play. Like Miller’s The Crucible, it dissects what happens to a community when trust breaks down and betrayal is not only sanctioned but required, and like that allegorical piece it’s compelling, but not pretty to watch.

François Truffaut would later be quoted in relation to Clouzot's depiction of life in Le Corbeau, that it was, "a fairly accurate picture of what I had seen around me during the war and the post-war period, collaboration, denunciation, the black market, hustling." Curiously, Truffaut was among the critics at Cahier du cinema who refused to acknowledge the worth of Clouzot's work, unfairly judging him to be part of a moribund, classicist cinema tradition that they despised, and this caused Clouzot much grief in the years to come.

As for Le Corbeau, as with most ‘resistance’ films, it’s probably best seen after viewing Marcel Ophuls’ The Sorrow and the Pity, as the received history of events seems wildly romanticised when compared to the reality of living with collaboration. The fact that Clouzot could sneak such a subversive film past the noses of the occupying Nazi’s is surely one of the great, though at the time unrecognised, feats of resistance in itself and the revelation of the banality of betrayal is a lesson to us all. Le Corbeau is a superb political film, one that still resonates today.

* Quentin Tarantino slyly used Le Corbeau as the film playing in the picture theatre in Paris during the occupation, in his bloody Jewish-Nazi revenge satire Inglorious Basterds.