Amore rules, ca va?

By Michael Roberts

"I think predictability has become the rule and I'm completely the opposite -- I like spectators to be disturbed." ~ Louis Malle

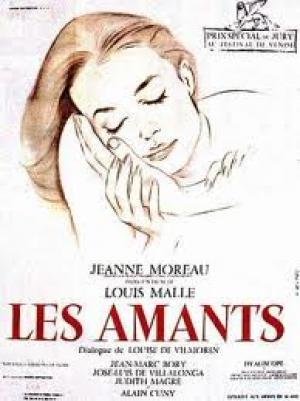

Louis Malle's 1958 follow up to his remarkable debut feature, Elevator to the Gallows again starred Jeanne Moreau, now a movie star because of that film and soon to be world cinema icon, in a film that became a scandal and a cause celebre. Les Amants (The Lovers) pushed the boundaries of what was acceptable in mainstream cinema and amazingly broke down archaic pornography laws in America, leading to a famous Supreme Court ruling. Malle also used Henri Decae again, the most influential cameraman in France in the 1950s, having made his reputation with Jean-Pierre Melville and soon to be the Nouvelle Vague darling, working for both Truffaut and Chabrol. Malle used a classic French novel as his source material and had the screenplay by novelist Louise De Vilmorin, who had written Madame De... , which became a hit film in the hands of master director Max Ophuls. This female perspective of the source material gives the resonance and detail that helps enable Moreau to deliver such an authentic and rich performance.

Jeanne (Jeanne Moreau) is a bourgeois house wife in an unhappy and affection starved marriage. Her neglectful husband Henri (Alain Cuny) is a publisher in a country town and allows Jeanne to spend a good deal of time with her best friend Maggy (Judith Magre) in Paris to counterbalance her dull provincial life. Malle opens his credits with a Brahms soundtrack, as far away from the Miles Davis in his debut film as he could get, and freezes on a faux 'map', the Carte du tendre by Madeleine de Scudéry from the seventeenth century, that includes a configuration alluding directly to the female anatomy! Mon dieu. It's a map of human desires, including an area marked 'Lake of Indifference', as well as one marked 'Dangerous Seas'. Malle is leading us into the terrain of the human heart, where maps are either non existent or useless. Jeanne is attracted to the superficial appeal of a polo playing Parisian playboy, Raoul Flores ( José Luis de Vilallonga) his oily charm part of Maggy's socialite set that she seems to aspire to. Jeanne's affair with Raoul is encouraged by Maddy who needs tacit approbation of her own lifestyle choices in Jeanne's embrace of the illicit relationship and of the world it represents. "Love agrees with you, you're unrecognisable" she says excitedly to Jeanne. Jeanne goes home to Henri and reflects "But still not so unrecognisable to him'?

Jeanne spends more and more time in Paris and speaks admiringly of Raoul to Henri, in a seemingly subliminal attempt to alert him to her infidelity and break him out of his torpor. She goes through the motions of being a couple with Raoul in the city of lovers, he takes her out in public, even to a fun fair, where the fake plane rides seems to mock her entree to a 'faux' jet set, an imitation jet for an imitation of love. Henri indeed suspects her affair, and despises the 'phony chic' Maggy and Raoul embody, he attempts to bring things to a head by conspiring to invite the Parisian couple to a country weekend, much to Jeanne's annoyance. Jeanne sets out on the drive from Paris alone for her home, and Maddy and Raoul follow after for their weekend with Henri, but Jeanne's car breaks down en route. A passing car stops to help, Bernard (Jean-Marc Bory) gives Jeanne a ride but has to stop to pay a visit to a sick friend, and during the journey Jeanne learns that Bernard is a man from her class who rejects it's phoniness and values. Maddy and Raoul arrive at the chateau well before them, Henri invites Bernard to stay the night having saved Jeanne on the road. Bernard silently watches the others exchange thinly disguised barbs during dinner, "a frontier is merely a line you step across", alludes Henri, aiming his observations at the convention Jeanne is breaking with her affair. Raoul and Henri regard the conversation as sport, where winning is important to each, and both hate losing. They agree to go fishing at dawn, Bernard feels bemused and goes off at the end of the night to enjoy some music and reading while the others retire as they will have to rise early.

Bernard is an archeologist, a man 'of the earth', not a 'fake', and an indication to Jeanne of an authentic life beyond the confines of the closeted one she's enjoyed. Jeanne strips off her 'society' garb, her black dress (who's she mourning?) and tied back hair, as she prepares a cleansing bath, she puts on a light flowing white nightgown, but goes downstairs where Bernard is listening to the moody and romantic Brahms. The room is empty so she walks out into the moonlight, finding Bernard outside and walking with him through the moonlit grounds of the estate. Both have drinks in hand, and during sounding each other out the glasses knock together to create a harmony, and soon both Jeanne and Bernard are in tune with each other and embracing the possibilities of love. "Is this a land you invented for me to lose myself in"? she asks as she gives in to his advances. She has crossed a frontier she'd only hoped might exist as she discovers her 'true' self, one that is truly unrecognisable. She experiences ecstasy, in its complete sense, that is ex (out) stasis (body/place), so in this sense it's a rapturous out of body/place experience. The lovers set Henri's fish free from their traps, an indication that the conventions that dictate the morning fishing party, the veneer of civility as rituals are observed amongst the 'civilised' class, no longer apply to them. Jeanne is at last 'unrecognisable', and next morning she severs all ties with her life to set off with Bernard. "I'm no longer myself" she says, having crossed her personal Rubicon.

Malle handles the delicate love scenes with a maturity and a candour that belied his 26 years, although he was in love with Moreau and having an affair with her at the time, so something of himself couldn't help but to be expressed. Tiny touches like the clock stopping in the bedroom as if time itself was standing still in the face of this beauty, the metaphysical transformation as Jeanne sheds one persona for another not yet known identity are filmmaking of a very high order. The so called obscene sequence is so soft and tender it's an indictment of the mores at the time that anyone could find it offensive. After a court case in America involving trying as distributor for exhibiting 'pornography' a Supreme Court judge no less declared that the film was not pornographic, stating "I know it when I see it". The themes spoke directly to the empowerment of women and would no doubt be embraced by the sisterhood of the 1960s as the feminist movement got up a head of steam, so to speak. Jeanne was a bourgeois woman in an existentialist crisis, who had everything at one material level, but owned nothing of value. Jeanne instinctively knew her life was a shell, pretty on the outside, but hollow within, and it's a tribute to the philosophy and depth of the writing that it offered no easy solution, even as the couple drive away she thinks, "already she had her doubts, but she regretted nothing". The mood that Malle and Moreau creates is almost ethereal at times, and hints at the transcendent power of something that can't be fully understood by the rules of this world, it's what music reaffirms in it's evocation of another level of comprehension beyond words.

The film was a huge hit in France and helped invigorate the industry and affirm that new talent was emerging, and Malle indeed was the trickle before the dam burst of the Nouvelle Vague the next year. Moreau was never more beautiful, and would enrich many a silver screen for many years to come, but with Moderato Cantabile, Jules et Jim and Antonioni's La Notte just around the corner, this represented a fertile and remarkable period for the iconic actress. Malle would soon go on to the mature glories of Le Fou Follet but in the interim delivered the lightweight madness of Zazie dans le métro and the fluff of the Bardot pieceVie Privée. He later combined the two iconic French actresses in the comedic western oddity Viva Marie. Malle revealed himself to be the great observer, if not the great humanist, of the new wave of French directors of the period - equally with Truffaut the inheritor of Jean Renoir's legacy. Malle would go on to live up to that lofty assessment, if not always, then time and time again at least, no small feat for sure, but he was never better than Les Amants, where his route through the dark, messy terrain of the heart proved so sure footed you'd swear he had a compass and a torch.