Kazan's socio-political noir

By Michael Roberts

'The motion pictures I have made and the plays I have chosen to direct represent my convictions.'

~ Elia Kazan

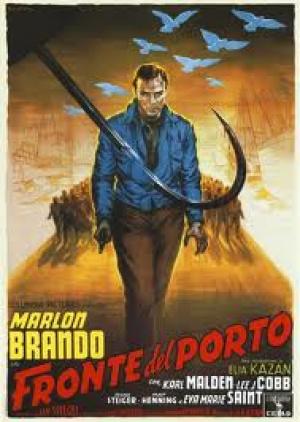

On The Waterfront stands as a seminal socio-political noir and contains many of the finest elements of classic Hollywood craftsmanship. Curiously Elia Kazan has more or less disowned the politics of this film and focused more on the love story aspect, but this is too disingenuous by half, as it’s the political aspect that elevates it beyond melodrama and gives the work its lasting resonance. The idea of the small corruptions that infect a community, that enable the blind eye to be turned and the lips to stay shut, this is at the heart of the piece, and all are embodied in Terry Malloy (Marlon Brando) and the dilemma he faces when he’s suddenly stirred from his moral slumber in confronting the consequences of his complicity in the murder of a fellow Jersey longshoreman.

The genesis of the project was two pronged. Arthur Miller and Elia Kazan were collaborating on a waterfront project called Red Hook, that was dropped by Harry Cohn at Columbia concerned that Miller was a communist and would be outed by the witch hunts. Later Miller and Kazan fell out over Kazan’s ‘friendly’ appearance before HUAC. Fellow friendly witness Budd Shulberg was working separately on a dockside piece, based on some key newspaper articles by Malcolm Johnson about corruption on the New Jersey waterfront and Kazan and he pooled their resources to create what was widely seen as an apologia for their testimony. Shulberg completed his first draft prior to giving his testimony so there may be a little chicken and egg in his case, but Kazan’s contributions reflected his HUAC experience, as admitted to in his compelling autobiography A Life. Kazan cast Frank Sinatra, a Hoboken native, in the Terry Malloy role, even picking out his costumes but producer Sam Spiegel knew that bigger star Marlon Brando would ensure more money from the film’s financiers and eased Sinatra out of the frame. Kazan was happy to get Brando, and a little surprised given Brando’s disappointment at Kazan’s ‘naming names’.

The opening sombre solo horn soundtrack, courtesy of Leonard Bernstein no less, coupled with Boris Kaufman’s evocative black and white tones indicates this is no lightweight love story. The leaders of the longshoremen exit their unpretentious little dockside hut to the more urgent rhythms of drums, the up-to-the-minute jazz sounds telling us this is a film of and for its time. Terry cradles a pigeon and calls out to Joey in a tenement window to go to the roof and collect it, thinking the Union heavies waiting there will only rough him up, they throw him to his death. Terry meekly protests to his brother Charlie (Rod Steiger) a key man in the Union, of his unease but gets told to be D&D, deaf and dumb, as Joey was a canary ‘Who could sing but couldn’t fly’. The code of silence is sacred amongst this clique, you never rat, and as the Government are conducting hearings into the Union waterfront practices that code was more important than ever. Johnny Friendly (Lee J Cobb) is an overbearing brute who runs the Union as a personal fiefdom, rewarding blind loyalty and enforcing the kick-backs and numbers rackets with cruelty and terror. Friendly is fond of Terry, who is not prone to overthinking situations, reminding him of his past as a boxer and keeps him around as a favour to Charlie, the Union lawyer. Schulberg introduces the idea that brains, like Charlie’s trumps brawn like Terry’s.

Joey’s sister Edie (Eva Marie Saint) is the catalyst for change, she’s intent on seeing her brother’s killer’s brought to justice. She shames the local priest Father Barry (Karl Malden) into helping, and after Terry becomes smitten by him she drags him into the process unaware of his complicity in Joey’s death. The clash of opposites in the convent girl Edie and the dockside boxer Terry provide the background for contrasting philosophies, his being ‘Do unto others before they do unto you’, hers is a simple notion of love and loyalty, but of an honest not blind kind. She sees in Terry a sensitivity that no-one else does, and she awakens in him an awareness of how corrupt things are. Brando’s unlocking of this tender side is the key to making the film work, and Marie Saint is heartbreaking, her ability to hit the right emotional pitch transforms the melodrama and gives it real weight. The love scenes are delicately handled, the vignette at the wedding, the scene in the park with the glove, all have a naturalism that keeps the core of the piece solid and heartfelt. Terry makes his stand, Charlie memorably trying to save his brother, but admitting in the process he has been part of the machine that’s ultimately sold him out. Charlie and Terry take the immortal cab ride to 437 River Street, the destination revealing Friendly’s deadly intent. Charlie, in an act of love, lets Terry out knowing that it means his own death, but finding redemption for himself in the process of sacrifice.

Father Barry convinces Terry that a gun is not the answer. Terry goes to the committee and testifies, but the redemption he feels is empty. Edie finds out about his culpability, but accepts his love and returns it, enabling him to see what real and honest love entails. Restless and still conflicted Terry goes back to the only work he knows. The racket of worker selection leaves Terry the only man not employed for the morning’s work and he storms down to the bosses hut to confront Friendly, watched by his co-workers. Terry is almost killed by the Union thugs but is able to drag himself into the warehouse after the men refuse to work without him. This ending was more hopeful than Shulberg’s original which had Terry die, and it’s obviously Kazan who is saying a defiant ‘I testified and I was right’ to his detractors in doing so.

The New York intellectual left spawned many great artists in the '30s who came to prominence, some like Kazan and Clifford Odets were indeed former CPA members and it says something that less than 20 years later the lurch to the right had left them isolated and exposed in a country confused, threatened and easily exploited by the politics of fear. The studios shamelessly went along with the resulting blacklist, a not-so-small corruption of its own. The stand Terry made was to recognise that the fertile ground upon which evil flourishes does not appear in a vacuum, it comes from good men doing nothing. Edie is the conscience and heart of the film, her love of family the catalyst for Terry to put things right, ironically with the only tools at his disposal, his fists. In the end he can only ever personally redeem himself, the corrupt politics and mob rackets go on it seems, even if the spotlight is occasionally turned on. The priest is left spouting sermon’s that point up the similarity in the words of Jesus and Marx, an irony lost at the time I’m sure (still is for that matter) but it’s only the unifying of community against the fascist Friendly that enables Terry to succeed at all. Post WW2 America’s liberals struggled with the semantic distinction between left leaning democracy and communism, and religion was as much a tool of state as means of enlightenment. Marx, it should be remembered, thought the great hope for a communist state was the USA, he would have been stunned that it emerged in Russia as it has a 90% peasant population, their lack of education usually meaning they were ripe for exploitation by the powers of the day.

Kazan originally had a deal to do the picture at Fox, home of the occasional ‘progressive’ picture thanks to Daryl Zanuck wanting to do ‘worthy’ type productions to impress the Academy, but Zanuck had a change of heart, coldly throwing Kazan and Shulberg out of his office, Kazan never returned. Ironically Spiegel inked a deal with Columbia and Cohn, who had rejected Red Hook, and Columbia duly collected the Best Picture oscar. Kazan’s rationalisations for his testimony over the years have been a battleground of opinion for and against, the most primary of sources being his own book. What is not often argued is the kind of fascist execution of state instruments he was set against. HUAC was a despicable use of an arm of government to vilify people who had belonged to legal organisations and were participating in freedom of speech and thought, the hysteria that the Red scare whipped up left liberal thinking, intellectual types scrambling for cover, wondering if they’d ever work again in their chosen career, or even if they would avoid gaol by standing up for their principles and not co-operating and ‘naming names’. Kazan’s choice may be morally compromised, but what of the behaviour of the right wing thugs, whose actions set the ground for the rise of Richard Nixon and his ilk? The Kennedy years seem like an aberration when viewed in that light.

Lee J. Cobb, who had a very similar arc of engagement with HUAC as Kazan, and who named names as well, said it best in his interview for Victor Navasky's 1982 book Naming Names - 'When the facilities of the government of the United States are drawn on an individual it can be terrifying. The blacklist is just the opening gambit—being deprived of work. Your passport is confiscated. That's minor. But not being able to move without being tailed is something else. After a certain point it grows to implied as well as articulated threats, and people succumb. My wife did, and she was institutionalized. The HUAC did a deal with me. I was pretty much worn down. I had no money. I couldn't borrow. I had the expenses of taking care of the children. Why am I subjecting my loved ones to this? If it's worth dying for, and I am just as idealistic as the next fellow. But I decided it wasn't worth dying for, and if this gesture was the way of getting out of the penitentiary I'd do it. I had to be employable again'.

Kazan was thick skinned and he survived what he knew would be a shit storm of criticism for what he did, unlike some others (Sterling Hayden for example) who regretted their decisions for life. Kazan was good hater, and went on to make great pictures, but none greater than this, the look and feel of a timeless noir and with the deft inter-woven brilliance of socio-political context for gravitas. Superior storytelling in a film for the ages.