Hitch ties himself in knots

By Michael Roberts

"The two things are absolutely miles apart. A mystery is an intellectual process, like in a whodunit. But suspense is essentially an emotional process. Therefore, you can only get the suspense element going by giving the audience information. And I dare say you've seen many films which have mysterious goings on, you don't know why the man is doing that, and you're about a third of the way through the film before you realize what it's all about. And to me, that's complete wasted footage, because there's no emotion to it." ~ Alfred Hitchcock on the difference between mystery (whodunit) and suspense.

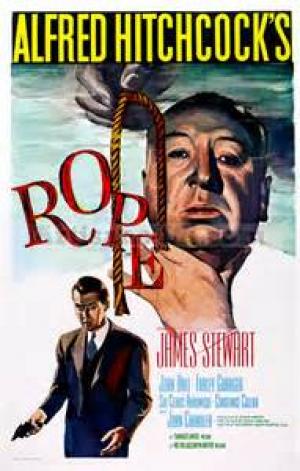

Hollywood was reluctant to tackle the controversial subject of homosexuality at any level in 1948, but Alfred Hitchcock successfully smuggled it in via the subtext of an old play based on the famous Leopold and Loeb case in his first colour film, Rope. It was also the first film he made with James Stewart, after Cary Grant and Montgomery Clift both turned it down because of the homosexual subtext, and it’s a wonder Stewart fronted up for 3 more films given the difficulties he experienced. Hitch chose to shoot it in 10 minute continuous takes, an unheard of innovation at the time, trying to recreate the live feel of theatre, causing Stewart to exclaim “why don’t you just set up seats and sell tickets.” John Dall and Farley Granger (both actors, as it happened, who were homosexual, a fact that Hitch would undoubtedly have been across) signed on for the roles of the young killers who plot the perfect crime, just for the thrill of it.

Brandon (John Dall) and Phillip (Farley Granger) strangle David, an old school chum, and put his body in a large trunk in their apartment. They hold a dinner party with invitees including David’s parents and girlfriend, and their old teacher Rupert (James Stewart) who they suspect would approve of their actions. During the party Brandon tries to keep Phillip’s nervousness in check, as well as his own desire to spill the beans to Rupert. David’s no-show generates consternation for his girl Janet (Joan Chandler) and his father (Cedric Hardwicke) as Rupert gets the distinct impression that Brandon and Phillip know ore about David’s non-appearance than they are letting on.

The play, written in 1929, is a repudiation of a type of elitist superiority extant at the time and of the putrid philosophy of eugenics, then popular within certain strands of fascist thought. The idea of intellectual superiority via genetic advantage and the idea that some ‘inferior’ people should therefore be eliminated creeps into the dialogue, “The Davids of this world merely occupy space” Brandon hisses. As Phillip wilts in the heat of the act, Brandon spouts casually evil rationalisations, “murder is a privilege for a few”, echoing the intellectual, hypothetical arguments Rupert had led in their college days. Brandon assumes Rupert would not only approve, but also admire his artistic flourishes, his “signature of the artist.”

Hitchcock battled the Hays Office as to the homosexual element of the film all through pre-production, and screenwriter Arthur Laurents was tasked with keeping the homosexual aspect of the project as discreet as possible. Laurents was the then lover of lead actor Farley Granger, and said in retrospect that he thought he’d succeeded because he was fairly certain that Jimmy Stewart never realised the central characters, and possibly his own, were gay. The Hays office exchanged memos with Hitch regarding ‘it’, the subtext that dares not speak its name, but around Hollywood it became known as Hitchcock’s ‘homosexual’ project.

Hitch would have been well aware that his young leads and screenwriter were all gay, and maybe Jimmy did too, but I think it’s more likely that they were more concerned with the anti-fascist component of the text, as both had seen the horrors on WWII up close. Hitchcock made a documentary for the War Offices of Britain and America on the horrors of the Nazi concentration camps and the holocaust. The result was so disturbing it remained unreleased in Hitchcock’s lifetime, eventually being screened in 1985. A passing reference to war is heard in Brandon's arch comment, "Good American's usually die young on the battlefield," fodder for the fascist oligarchs no doubt. The elitist and intellectual games that caused the twisted Brandon to justify his actions is found in a short exchange where Rupert is out to shock David’s conservative Aunt, where he jokes about “cut a throat week”, but ultimately Rupert is repulsed by the realisation Brandon has taken his intellectual parlour game to its grizzly conclusion, “I thank you for that shame”, is his shattered comment.

Hitchcock was also distracted by the technical aspects of the film, a property he would have ideally wanted to film in one take, but as the camera spools of the time were limited to 10 minutes he had to devise ways of filming in 10 minute takes. He solved the puzzle by constructing an elaborate set with moving walls and sliding furniture that could be moved as the actors repositioned. It was a logistical nightmare for both technicians and actors alike, knowing that any small mistake would ruin a can of film each time. Hitch had worked in the claustrophobic confines of a single set in his excellent wartime thriller Lifeboat, and would again with his masterful Rear Window, but the long takes on Rope proved arduous and difficult.

The central leads do very well, considering the pressures and limitations and Dall is particularly effective as the nasty Brandon. Dall was a stage actor who was woefully under-used in features and apart from Rope his only notable leading effort is the pulsing Noir, Gun Crazy, from 1950. Brandon’s overt narcissism and latent attraction to Rupert drives the narrative and gives room for the balance provided by Granger’s twitchy accomplice. Hitchcock deliberately has them come down from the high of the murder as if they’d just had sex together, hot and breathy they light what for all intents and purposes are post-coital cigarettes! If the folks in Iowa had not twigged by now that these boys were batting for the same team, the folks in New York certainly did. Granger is very good as the distraught Phillip, caught by the charisma of his lover, and Hitchcock was impressed enough to cast him again 3 years later in Strangers on a Train. Stewart is a little miscast as Rupert, but provides enough stoic decency to make the part work, though not what it might have been in the hands of a George Sanders.

Jimmy Stewart was actually at a low career ebb by the time he made Rope, opting to work with the master even if the project was widely unloved. He’d won a Best Actor Oscar before the war but made no films for 5 years as he signed up for the Air Force and rose to the rank of Colonel. He made the perennial It’s a Wonderful Life for Frank Capra as his return to the screen, but the film flopped upon release, as did his next film, written by Robert Riskin and directed by William Wellman, Magic Town. Rope didn’t fare much better and it with his film career in jeopardy that he returned to the stage to take the central role in Harvey, before he opted to make some westerns with Anthony Mann as a last resort. The Mann cycle of films became hugely popular and Stewart’s association with Hitch paid off handsomely with a couple of ‘50s masterpieces in Rear Window and Vertigo.

Hitch rounded out the cast with a fine ensemble of quality players, and all provide the kind of effortless verisimilitude needed. Cedric Hardwicke is very touching as the concerned father, fielding calls from his sick wife as to the whereabouts of his missing son, “he’s an only child you know” he softly says, as Hitch subtly amps up the ramifications of the event. The tragedy at the heart of the matter, the loss of a life and son, is subsumed in the focus on the minds of the murderers, but in one line we are reminded of the human tragedy unfolding. Constance Collier is delightful as the Aunt, and prefigured a type Hitch would use again, the elderly woman infatuated with the macabre, in Strangers on a Train.

Hitchcock was finally free of David Selzick after many years, and his choice to strangle ‘David’ at the top of the film is indicative of the kind of dark humour he enjoyed. Arthur Laurents advised Hitch not to show the murder and then the film would have elements of a whodunit, but Hitch refused. He always preferred to let the audience in on a secret rather than frustrate them by having them play guessing games, and rarely did he deviate from that trope. He shows the murder and we know the kind of socio-path we are dealing with from the word go, to not show it would have made it a different film.

Rope was not a huge success at the box office, and was not a film Hitchcock remembered fondly as a result, a sombre and serious film it nonetheless remains a fascinating exercise in film-making. He certainly made sure that the next time he used Farley Granger in Strangers on a Train, he’d make it an entertaining ride, and it is the case that he never really made a film as bleak and as serious as Rope again, spicing nearly all of his subsequent films with dollops of dark humour. There is very little humour in Rope, and ultimately any conspiratorial snigger will regurgitate in the viewers throat, as it does with Rupert, which is entirely the point of the film.

The master may have been slightly distracted by juggling a lot of different elements and been frustrated by parts of the production but ultimately it exists squarely in the Hitchcockian universe, where life feels strangely strange and oddly normal. His eye for detail and elegant visual instincts has meant that it has aged better than he would have guessed, but then that can be said about nearly all of his work.