Welles a-mazes again.

By Michael Roberts

'If you want a happy ending, that depends, of course, on where you stop your story.' ~ Orson Welles

Like most of Orson Welles’ post RKO films the genesis of this one was far from straightforward. Orson needed money in a hurry for a stage production he was involved with and simply phoned Harry Cohn at Columbia with a scheme to direct a thriller for which he had no script, as Welles was still married to one of Columbia’s biggest stars in Rita Hayworth Cohn agreed. The part of the femme fatale was originally written for an unknown actress but apparently Hayworth convinced Welles to give it to her in an attempt to save their by then rocky marriage. Welles re-modeled the famous long haired redhead into a short haired blonde, to the explosive wrath of Cohn, and set about putting his inimitable touches to a noir piece every bit as convoluted as Hawks' The Big Sleep.

A chance encounter in Central Park and an Irish voice-over kicks off the story of ‘Black’ Irish Mike O’Hara as he sets about saving glamour girl Elsa Bannister (Rita Hayworth) from a mugging, but right from the start things don’t add up, as Welles undermines the action at several points with doubt about motive and intent, eg ‘Why does she throw a bag with a gun away just before the mugging’? and it causes the audience to always be unsure what’s really transpired. Elsa is married to noted lawyer Arthur Bannister (Everett Sloane) and Welles famous distaste for lawyers is revealed at many points in the narrative, not least in the physical affliction he’s invested with, although Welles added a separate motivation was his dislike of Sloane’s mobility as an actor and the walking sticks would neutralise this and give another dimension to the characterisation. Win-win. Elsa offers Mike a job on board their yacht sailing to ‘Frisco via the canal, but although smitten by her beauty he declines, sensing trouble in store. Bannister himself comes and asks for Mike and in a drunken session Mike relents ’you swallow the lies you tell yourself’ and signs up. They set sail for Acapulco where Bannister’s partner Grisby (Glenn Anders) joins them. Grisby sees the attraction between Mike and Elsa get serious and offers Mike a job for the money he would need to run away with Elsa, to ‘kill’ Grisby, or fake his death.

Mike reluctantly goes through with the ‘murder’ and signs a confession to the effect. Grisby is actually murdered and Mike is the fall guy. Bannister convinces Mike to engage him as his defense attorney and a trial begins, at one point he comically says to Elsa ‘I wouldn’t trust him with my wife’, a twist on the stock phrase with decided Elmer Fudd overtones. Welles has more fun with lawyers as Bannister cross examines himself on the stand! The whole courtroom scenario is seen through the prism of a chess game. As the guilty verdict comes down Bannister confesses to Mike he set out to lose the case and take his revenge for Mike’s cuckolding of him. Mike escapes custody by faking a suicide attempt with stolen pills, he manages to get to a Chinese theatre in Chinatown, but Elsa, fluent in mandarin from her days in Asia, tracks him down. Mike suspects Elsa killed Grisby, in league with her husband and finds the incriminating gun in her purse, but the drugs take effect and Elsa’s Chinese servants take Mike to an abandoned fun fair to hide him. Mike comes to, and in a surreal sequence runs around the park’s hall of horrors, eventually falling into a hall of mirrors where Elsa finds him. Bannister joins the party and a shoot out erupts where Elsa and Bannister effectively become the sharks who eat themselves that Mike had recalled in an earlier story on the boat. Bannister says ironically to Elsa ’you’re gonna need a good lawyer’ before she shoots at him, reflection and reality interchangeable as glass and schemes shatter with equal precision. Bannister is left dead and Elsa dying, who looks up at Mike as he walks away, ‘Give my love to the sunrise’. Mike exits the fun fair as if waking from a dream hoping to ‘live so long I’ll forget her, or die trying’.

Welles created a hymn to artifice in The Lady From Shanghai and his skewered vision highlighted the emptiness of the idle rich and the perversities they are prone to. His theatrical background should not be forgotten in either the tenor of the piece or in the adoption of the convincing Irish accent, recalling his couple of years as a young man working with a theatre company in Dublin. The grotesque characterisations of Bannister and Grisby and the unnerving extreme close-ups and camera angles all designed to create a heightened reality where nothing can be taken at face value, an environment where an innocent like Mike is truly at sea. Like Hitchcock and his legendary MacGuffin the plot is not important, it’s a device from which Welles can hang his set pieces and commentary, and like Hitch the world he creates is not meant to be seen as a real one, it’s a reflected dream of a crafted and stylised reality, To quote Jean-Pierre Melville, “All my films hinge on the fantastic. I’m not a documentarian; a film is foremost a dream, and it’s absurd to copy life in an attempt to produce an exact re-creation of it. Transposition is more or less a reflex with me; I move from realism to fantasy without the spectator ever noticing.”

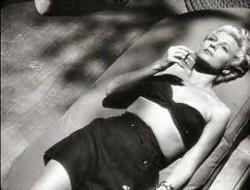

Harry Cohn certainly noticed what Welles did to his star and was not impressed, famously saying he’d never employ a writer-director-actor like Welles again as he couldn’t fire anyone! Nevertheless he re-cut the film, losing most of the surreal amusement park sequence and slicing almost an hour from Welles’ 2 1/2 hour cut. It’s not surprising that American audiences rejected the version of Rita Hayworth that Welles presented here. Her Elsa is a complex woman and her motivations are less than clear, although it’s certain that this is a woman who uses sex as a weapon in every nasty way she deems necessary in order to scratch out an existence in a rich man’s world. It’s obvious her wealthy husband is physically incapable of sexually satisfying her and it’s no accident that Mike is ’shanghai’d’ onto the boat, indeed with her husband doing the recruiting it’s implied that he is complicit in having her ‘serviced’ by the big Irish sailor. Hayworth makes a reasonable fist of the part and is both coquettish and edgy, a woman caught in a spiral of conflicting impulses. We’re never sure of her motivations because she’s never sure of them herself.

Rita Hayworth battled stereotypes and a studio system run by 'a monster' in Harry Cohn, who abused and bullied her. She endured sexual abuse from her father as a child (according to Welles) and worked hard to find decent roles to prove she had more to offer than her sexualised Love Goddess image. Her beauty disarmed and entranced men for decades and Welles was no different, but the marriage only lasted a couple of years, producing a daughter and this film, evidence of Hayworth's acting talent in the hands of a curious and adventurous director.

It was 10 years before Welles worked in Hollywood again, spending the intervening years mostly in Europe, his spiritual home it seems, although the time roughly coincides with the McCarthy era witch-hunts that Welles as a prominent liberal with many conservative enemies because of Citizen Kane would surely have been caught up in. Effortlessly stylish and compelling viewing it’s again testament to Welles' ability that he could produce something so fractured and potent within a studio system more accustomed to smooth edges and watered down punch.

*nb. The boat for all the Mexico scenes was Errol Flynn’s, and he even appears un-credited in a bar scene at one point. Errol and Rita together on the same boat, now there’s a thought!