Ray of dark

By Michael Roberts

"You like these films, but you can't imagine how often they represent only 50% of what I wanted to do. You have no idea how I had to fight to achieve even that 50%."

~ Nicholas Ray

Nicholas Ray made an assured and confident debut with this Film Noir version of the 1937 novel by Edward Anderson, Thieves Like Us, produced and supported at the mighty RKO by former Orson Welles intimate John Houseman. Houseman thought Ray ideal to helm the project as he knew the world of the deep south intimately, having been an assistant for Alan Lomax during his seminal field recordings. Dore Schary was a noted liberal and for a short time, prior to the autocratic takeover by Howard Hughes, controlled the production slate at RKO and was keen to give new directors a chance. He green lit the project and the former New York stage figure set about casting largely unknown actors to play the key roles. Farley Granger was discovered by Ray at a party at Gene Kelly's house, and Ray asked him if there was a young actress he'd be comfortable with to play against him, and Granger nominated Cathy O'Donnell. Robert Mitchum also was keen to be involved as he knew that world too, but missed out on the part of Chicamaw because he was deemed to be a star on the rise, and the role beneath him.

Ray opens proceedings with a fake, glamour Hollywood romance view of the young couple involved, in effect showing a dream life they will never know. Ray then cuts to possibly the first use of a helicopter to shoot an action sequence in a feature film, and from the outset the idea that events are in a continuous state of motion is established. Three convicts T-Dub (Jay C. Flippen) Chickamaw (Howard Da Silva) and Bowie (Farley Granger) have escaped from a prison farm and hole up with Mobley, a brother of Chickamaw and his young daughter, Keechie (Cathy O'Donnell). Bowie is the 'kid' of the trio, the others are hardened bank robbers, and soon they are plotting to continue their criminal exploits together. Bowie is appalled to learn that a getaway car will cost them $1500, the seller profiteering because of the nature of the buyer's, but the elder thugs realise it's the cost of doing their kind of business, labeling the seller a "thief like us". Ray deliberately establishes that part of respectable society secretly profits off the criminal, blurring the lines between notions of good and bad, eliciting sympathy for the younger criminals as events unfold.

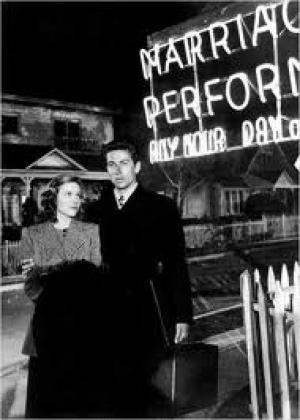

Bowie and Keechie are drawn to each other, both are essentially in a state of suspended adolescence, no longer children and not really adults, and will need to struggle together to come to terms with the deep feelings they unlock in each other. This journey is complicated by Bowie's inability to extract himself from the demands of his partners, even though Keechie instinctively knows it's a doomed arrangement. Bowie is encouraged by Chickamaw to 'look and act like other people', and this is Bowie's dilemma, he is an outsider who doesn't have the emotional or intellectual tools to get inside. Bowie dreams of an escape for the couple to Mexico, but goes back to the life of crime once Chickamaw comes knocking again. Keechie's simple faith in Bowie gives him something to hold on to, but the world of the criminal is duplicitous and soon comes the inevitable. betrayal. Bowie grasps at his Mexican illusion by re-visiting the cheap marriage celebrant who hitched the young couple, but as he put it, "I won't sell you hope where there is none".

Nicholas Ray came to Hollywood via the New York stage, a contemporary and friend of Elia Kazan's and in some ways what he saw in Granger and the performance he elicits from him presages the 'new man' of Montgomery Clift and especially Marlon Brando. Granger has a sensitivity to him that is decidedly feminine in its energy, several steps removed from the 'solid man' stoicism of throwbacks like T Dub and Chickamaw. As with most Noir protagonists the couple are from the lower depths, the working classes and Cathy O'Donnell's Keechie has a quiet earthiness that grounds the story in a reality rare for Hollywood at the time. The proletarian roots of the couple are obvious in the parts of the world they inhabit, the cheap hotels and garage hangouts, and they look decidedly out of place once they venture into the more urban or 'sophisticated' world of the nightclub, where Ray employs Marie Bryant, an old Broadway pal, to sing Your Red Wagon.

The young couple seem to understand the doomed fatalism they embody, indeed their march towards the marriage office seems more like a funeral procession, they seldom smile, and when they do it's a shock, and only for a brief instant as if this world and these conditions can't last. Where 'normal' people live by day, enjoying the sun and the freedom, Bowie and Keechie are fated to live by night, forever looking over their shoulders. Ray shows an impressive visual command, shooting angles that enliven and enrich the scenes, like showing the robbery from the outside perspective of Bowie's getaway car, rather than simply showing us another bank hold up. Ray's use of sound and atmosphere also reveals an inquisitive and searching eye and ear, where no detail is too small to contribute to the overall impact of the end result. It's that level of detail and keen observation that makes They Live by Night one of the great debut features in cinematic history. Howard Hughes took over RKO and oddly shelved the film for 2 years, even though he like Ray and used him as a kind of Mister Fixit with other properties, including Von Sternberg's Macao, as Hughes tried to put his stamp on the studio.

Hughes supposedly protected Ray from the blacklist, where his New York Group Theatre background should have guaranteed him HUAC attention, and his Hollywood start was after all as an assistant to Kazan on A Tree Grows In Brooklyn. Howard Da Silva was a victim of the blacklist however, and went back to the New York stage in order to find work during the 1950's. They Live By Night was nevertheless much admired within insider Hollywood circles, and after private showings it caused Hitchcock to cast Farley Granger in Rope, and subsequently in the superb Strangers On A Train. Humphrey Bogart noticed the film and asked Ray to direct him in On Dangerous Ground, and it ultimately led to another collaboration and one of Bogart's best films, the Film Noir of In a Lonely Place. Ray went on to enjoy a singular, if maverick career, producing such special oddities as Johnny Guitar, as offbeat a film as Hollywood ever threw up, and also mainstream hits like the energetic and iconic Rebel Without a Cause.

Robert Altman revisited the book in his very fine 1974 film Thieves Like Us, and brought an agreeable counter culture ambiance to the tale, creating a worthy Neo-noir in the process. As fine a filmmaker as Altman was, the story exists as if tailor made for 1940s Noir, and plays out perfectly in Nicholas Ray's shadow world at the dark end of the street.