The Daughter also Rises

By Michael J. Roberts

"You don't learn from successes; you don't learn from awards; you don't learn from celebrity; you only learn from wounds and scars and mistakes and failures. And that's the truth." ~ Jane Fonda

Jane Fonda was born to Hollywood royalty in 1938, the daughter of a distant and remote monarch in father Henry and a troubled mother who would commit suicide when Jane was twelve. Jane spent most of her young years in awe of her frequently absent father, and eventually followed Henry into the family business (as did her younger brother Peter) and spent the rest of his life trying to get out from under Henry’s giant shadow. She baulked at a career on stage or in films and professed no interest in acting until her early 20s, when Lee Strasberg provided the lightbulb moment by affirming her talent as she tentatively dipped a toe in the water, and from there she trained her trademark intensity into carving a name for herself. She threw herself into her many endeavours, acting, marriage, political activism, fitness/exercise guru and embarked upon a 60 year plus career that would have many millennials well aware of the grand old lady of stage and screen - just as many of them would be saying Henry who? Her screen resume and fearsome talent would lead to her name embellishing the surname further, and for Jane Fonda to be a byword for class, commitment and dignity in the acting profession.

"I don't want to make a cheap analysis, but when you have, like I did, a father incapable of showing emotion, who spends his life telling you that no one will love you if you aren't perfect, it leaves scars." ~ Jane Fonda

After a six-month stint in Paris studying art in the late 1950s, Jane finally followed in her famous father’s footsteps and tripped The Great White Way in 1960 with a starring role in There Was a Little Girl, for which she won the first of two Tony Award nominations – the second coming a mere 49 years later! She made her film debut in the same year for family friend Joshua Logan in the rom-com Tall Story. Her second film was the dark toned Walk On The Wild Side for HUAC backlisted Edward Dmytryk, with Laurence Harvey and Barbara Stanwyck. She made another couple of Rom-Com’s for George Cukor and George Roy Hill but the tone was set for her ingenue phase and she struggled to break away from Broadway derived properties that starred her against equally preppie types, like Rod Taylor in Sunday In New York.

Jane fought against the stereotyping by going back to France to make two films, one for French cinema giant René Clément called Joy House, opposite Alain Delon and Circle of Love, an unremarkable film for Roger Vadim, who became her first husband. She effectively shook up her Hollywood image with the comedic western Cat Ballou in 1965 and followed it up with a fine piece for Arthur Penn in The Chase, opposite Marlon Brando and Robert Redford. She made the Broadway play Barefoot in The Park with Redford again, before she wrong-footed everyone by starring for husband Vadim in the bizarre sci-fi Barbarella. After a break in France she returned to the US and to a film that put her range and power on full show, Sydney Pollack’s masterful, They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? The effort earned her an Academy Award nomination for Best Actress and a Golden Globe nomination in the same category.

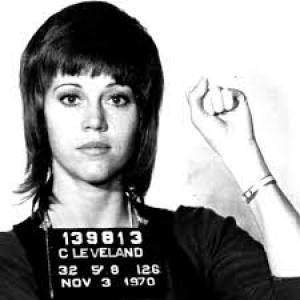

Fonda was extremely active as a political agitator during this period, especially in concert with then boyfriend Donald Sutherland. She graduated from protesting for Civil Rights in the 1960s, to protesting for Women's Rights and demanding an end to the war in Vietnam through the 1970s. The pair professionally teamed up for Fonda’s career high effort in Alan J. Pakula’s brilliant paranoia thriller, Klute and again in the offbeat Steelyard Blues for Alan Meyerson. Klute earned her another Oscar nomination and a Golden Globe win for the role of the edgy call girl, Bree, a role that seemed to be dredged up from some dark place in Fonda's psyche. She combined interesting work with her activism, and both coalesced in Jean Luc Godard’s Tout Va bien, a typically obtuse, circular Godard-ian riff on communism, capitalism and commercialism. Fonda handles the brief very well, but the shit hit the fan the same year when Fonda became Hanoi Jane in the eyes of the world due a lapse in judgement resulting in one notorious photograph of her on a Viet Cong tank.

Fonda dominated the next decade of American film as the A-List actress du jour and worked for a succession of top directors like George Cukor, Joseph Losey and Sidney Lumet. She scored stellar hits with Fred Zinnemann in Julia, and Coming Home for Hal Ashby, both films winning her Best Actress Oscars and Golden Globes. She continued her fine run of significant films including Comes a Horseman for Alan J. Pakula, California Suite for Herbert Ross, The China Syndrome for Alan Bridges and another Sydney Pollack hit with The Electric Horseman, another Redford co-star. She finished the 1970s with possibly the biggest commercial hit of her career, and a film she produced, the slick and subversively feminist workplace satire/comedy, 9 to 5.

"I don't think there's anything more important than making peace before it's too late. And it almost always falls to the child to try to move toward the parent."

~ Jane Fonda

During the next decade she scaled back her film work and started with an intensely personal project, On Golden Pond. The film had her co-starring with her father for the first time, in a property that Jane had purchased specifically so she and Henry could do it, a story about a father and daughter with a fraught history. Katherine Hepburn co-starred, and Henry Fonda won an Oscar, as did Hepburn. Henry died within weeks of the Oscar ceremony, but father and daughter had reconciled, and the film remains a beautiful, if sentimental ode to family connection.

Fonda made Rollover, her third and last film for Pakula and the lesser of their collaborations, before she made the brilliant and under-rated Agnes of God for veteran director Norman Jewison. She made one of the best films of her career next, one that consistently falls beneath the radar, with The Morning After, a moody neo-noir for Sidney Lumet and co-starring Jeff Bridges. She rounded out the decade with a part opposite Gregory peck in Old Gringo, and in Stanley and Iris, a solid film for Martin Ritt starring opposite Robert De Niro.

Fonda then took a 15 year sabbatical while she focused on other aspects of her life and returned in the broad, if unremarkable Monster-in-Law. Fonda is never less than watchable in any project she takes on, but most of the handful of roles she’s taken on since would not rate a mention when stacked against her golden period. The exception to that is the quirky, idiosyncratic Youth, a film she made in 2015 for Paolo Sorrentino, co-starring Harvey Keitel and Michael Caine. For Fonda and Caine it was a reunion some 48 years after they’d made Hurry Sundown for Otto Preminger in 1967.

Jane Fonda had the fortitude to survive a perilous childhood, topped off by the suicide of her mother, and to rise to the top in an industry where her father was a legend and would therefore make it difficult for her to accept she’d succeeded on her own merit and talent. She brought a vulnerability and a fearlessness to her craft and created a body of work which she could be justifiably proud of, even if her opportunities were compromised by her commitments elsewhere. Maybe even more importantly Fonda was a decent human being, a beacon of humanity and heart, even if she was misunderstood and demonised by the right wing, she can hold her head high that she was on the side of the angels during troubled times. Long may she fly.