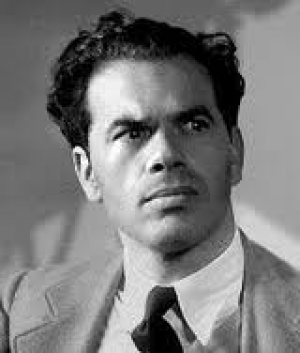

The Capra conundrum

By Michael Roberts

Capra is known these days for a particularly 'corny' and sentimental style of filmmaking, which is both fair and unfair. Sentiment on its own is no reason to condemn an artist, but when it's used for shameless manipulation it crosses a line, and that's a line Capra played hopscotch with his entire career. A driven man who pulled himself out of poverty by sheer force of will, he learnt his trade in the rough house of silent era Hollywood and the comedies of Hal Roach and Mack Sennett, eventually finding a solid place for himself under the "benevolent dictatorship" of Harry Cohn at Columbia. Capra proved himself an efficient 'factory' man, helming a conveyor line process of unremarkable films, 9 in his first year alone at Columbia.

Capra was sharp enough to know that the sound era required good writers of dialogue, and things changed for Capra inpartnership with a string of great screenwriters, notably Jo Swerling, Sidney Bucman and of course, Robert Riskin. Riskin entered the frame in 1930 and the depression era social sensibility he brought with him was perfect for the times, even if Capra personally railed against Roosevelt and the New Deal that eventually saved the nation. Capra cast his lover Barbara Stanwyck in the first of the Riskin properties The Miracle Woman, and his mature and unfussy directing and sure handling of the scripts created a signature style that endured for the next 10 years. Capra made the remarkable The Bitter Tea of General Yen, again with Stanwyck, and enjoyed a massive hit with another feisty woman in Platinum Blonde, with Jean Harlow.

The ambitious Capra was a classic case of an immigrant trying to be more 'American' than those born there, more successful than any native, and was always overcompensating to prove his loyalty and patriotism. He both salivated over and coveted an Academy Award as evidence of his stature and credibility and was sure he'd win for Riskin's witty social satire Lady For a Day. he missed out completely but his next film made up for the oversight, and then some. Capra became a superstar director with the spectacular success of It Happened One Night, a blockbuster starring Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert. In partnership with Riskin he won an astounding 3 Best Director Oscars in 5 years, with Mr Deeds Goes to Town and You Can't Take it With You, and gave career best roles to Gary Cooper and to Jimmy Stewart in Mr Smith Goes to Washington, written by Buchman. Cooper and Stanwyck starred in the last Riskin/Capra collaboration, the remarkable essay on American fascism, Meet John Doe, made just as America was belatedly entering WWII.

Capra was then at his peak as he came to be a kind of Stephen Speilberg of his time, populist and incredibly popular, and his work seemed to represent the aspirations and struggles of the common man, with whom it resonated. This dimension, of course, was Riskin's input and not that of arch capitalist and political conservative Capra. It seems Capra was happy to maintain the patina of a concerned and empathetic social commentator as long it was box office, and the illusion met with spectacular success. Riskin and Capra finally fell out, essentially over Capra's egotistic and demanding character, and Riskin went his own way.

Capra was the man with the golden touch during the pre-war years, and spent the war in service producing and directing propaganda films for the US military. After the war he formed Liberty Pictures with fellow directors William Wyler and George Stevens, and set about recruiting Jo Swerling to tidy up an adaptation of a modern variation on Charles Dickens, Its a Wonderful Life. He signed Jimmy Stewart to play George Bailey, spent more money on it than any film he ever made and succeeded in producing a career defining work of art that flopped upon its initial release. Capra spent the rest of his career as a shell of his former self, unsure and uncertain of what to direct, eventually he settled on second rate remakes of his own work, even including a couple of Riskin scripts.

Ironically, given Capra's personal right wing leanings, he came under the scrutiny of HUAC during the communist witch hunts in the late '40s and early '50s, and the consensus seems to be that while he avoided the blacklist, he was definitely on the 'greylist'. Capra's reliance on left leaning writers during his halcyon days came back to haunt him, as over a dozen writers who had contributed to Capra films were suspect in the egregious committee's eyes. Capra was tarred by association, and it's possible that only the likes of Ward Bond and the shrill and deranged anti-pinko Adolphe Menjou, founder members of the poisonous Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Values, being former stars in his films, may have helped him avoid a worse fate.

Regardless of Capra's true political positions he managed to direct some brilliant and entertaining films that remain so to this day, even if he assiduously hacked away at his own reputation in his self mythologising autobiography, The Name Above The Title. Capra downplayed Riskin (and every other writer's) input into his work and then set about decrying the new permissiveness of American films in the '70s, and the move away from Christian values in modern films. Oddly enough, his best work transcends the era in which it was made, and remains redolent with humour and humanity, love and pain and the whole damn thing, and is a legacy that a 5 year old Italian kid who sailed into New York harbour in 1902 should be proud of.

* I heartily recommend Joseph McBride's superb biography, The Catastrophe of Success for a full and riveting insight into Capra.

Also recommended;

American Madness

The Miracle Woman

Platinum Blonde

You Can't Take It With You

Mr Deeds Goes To Town

Mr Smith Goes To Washington

Lost Horizon

Lady for a Day

Arsenic and Old Lace

For Fans Only;

State of the Union

Best Avoided;

Here Comes The Groom

A Hole in The Head

Riding High

A Pocketful of Miracles