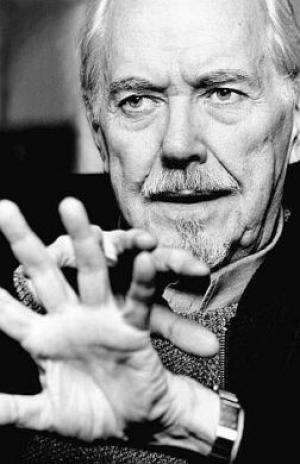

American iconoclast

By Michael Roberts

"I am not an expert. That is someone else's job. If I were expert, the approach would be all wrong. It would be from the inside. I am a blunderer. I usually don't know what I am going into at the start. I go into the fog and trust something will be there."

~ Robert Altman

By the time of Altman's first smash hit he was a veteran of nearly 20 years in the industry, having gone to California to try his hand at screenwriting, after spending WWII as a pilot. Failing as a writer he ended up making industrial promotional films and documentaries in the mid-west before he sold a film to United Artists called The Delinquents. The almost documentary realism of that film led to a move back to Los Angeles and a quick low-budget cash in on the death of James Dean, with The James Dean Story. Altman eventually ended up with a thriving career as a TV director, working on most major late 1950’s and 1960’s series before a couple of undistinguished features led to him being low on a list of potential directors for Ring Lardner Jr's script for M*A*S*H, an unexpected career changing smash hit.

Most experienced directors had passed on the anarchic war comedy, and 20TH Century Fox were more focused on Patton, a war film with a major star and four times the budget, so Altman got his chance to stamp his signature on the film. Donald Sutherland and Elliot Gould were the two lead stars, then not marquee names, and they were more concerned with Altman’s methods and tried to have him sacked, to no avail. The runaway success of the film propelled them both to major league stardom and propelled Altman into the first rank of American cinema directors as he managed to carve a career that saw him exit and re-enter that stratosphere several times.

"Making a movie is like chipping away at a stone. You take a piece off here, you take a piece off there and when you’re finished, you have a sculpture. You know that there’s something in there, but you’re not sure exactly what it is until you find it.” ~ Robert Altman

Emboldened by the success of M*A*S*H, Altman would plot a path through personal projects that often baffled and intrigued outside spectators. He immediately set up a production company, Lions Gate Films, and made the oddball Brewster McCloud, a critical if not commercial hit, before he again struck gold with his masterful anti-western, McCabe and Mrs Miller. Already some of Altman’s now familiar tropes were forming, the undercutting of cinema convention, the episodic nature of his films, the peppering of the support cast with an almost stock-company roster of familiar faces, and the absolute singularity of his mis-en scene. Altman also demonstrated a lifelong pattern of repetition aversion by doing a psychological horror film next, Images, a film he’d been thinking about for some years and more in the vein of a Joseph Losey or Ingmar Bergman than mainstream Hollywood. Images won Susannah York a Best Actress gong at Cannes and kept everyone guessing what Bob would do next?

Altman promptly produced two brilliant films back-to-back, both polar opposite in theme and genre, The Long Goodbye and Thieves Like Us. Elliot Gould reunited with Altman on the former film, a genre defying, neo-noir update of a Raymond Chandler novel with the laconic Gould as detective Philip Marlowe but the film failed to find a wide audience. Thieves Like Us was Altman’s beguiling take on the lovers-on-the-run genre which seemed to be having its time in the sun during that period with Scorsese, Malick, Spielberg and others all following in Bonnie and Clyde’s bloody footsteps, and it starred Keith Carradine and Shelly Duvall. Altman followed with another Elliot Gould featured effort, pairing him with George Segal for the effective gambling themed opus California Split before he moved on to what is widely recognised as his masterpiece, the sprawling, one of a kind, Nashville.

Nashville was a satire with little precedent in American film but it confirmed and enhanced Altman’s status, even as it confused mainstream America and pissed off Nashville’s country music community royally. It was Altman’s comment on America’s 200th birthday but many were scratching their heads after they unwrapped the birthday present, many still do. Nashville is where all of Altman’s foibles and tropes come together with overlapping dialogue and a mighty ensemble cast traipsing a chaotic two-step to Altman’s shifting tempos. It remains his signature dish, even if he continued to concoct magnificent banquets like The Player and Short Cuts near decades later.

In the interim, Altman parlayed his status into working on a string of Hollywood studio backed projects with mixed artistic returns and even more mixed acceptance. Linking up (for once) with Paul Newman, one of the biggest Hollywood stars of the era, not to mention Burt Lancaster, Altman made a revisionist western with Buffalo Bill and The Indians, written with long-time collaborator and future director Alan Rudolph. On firmed artistic ground was his superb evocation of ambiguity and mood, 3 Women, starring Shelly Duvall, Sissy Spacek and Janice Rule and this existential masterpiece remains on of Altman’s finest works. After another modest triumph with A Wedding, a couple of critical misfires in Quintet and A Perfect Couple, Altman succumbed to the lure of the blockbuster and filmed what incorrectly became labelled as a major league flop, Popeye, with Robin Williams and Duvall. The film was as sprawling and chaotic as any Altman opus and it made money, but it was such an odd fit in Altman’s oeuvre that it is probably regarded more as a Robin Williams film in retrospect.

The experience saw Altman retreat from major studio associations entirely and embrace the world of Independent Film, producing low budget gems (all based on theatrical plays) in Come Back To The Five and Dime Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean, Streamers, Secret Honour and Fool For Love, the last with playwright Sam Shepard. Altman saw out the 1980’s with other smaller projects before steamrolling back into Hollywood consciousness with the mighty, The Player, as acerbic a vision of the Hollywood system that has ever been captured on film. The film was embraced and Altman placed back at the top of the tree where he promptly made another masterpiece, Short Cuts, a treatise on humanity based on a series of Raymond Carver short stories. The inter-linking stories and multiple character episodes of Short Cuts make it a thoughtful companion to the more raucous Nashville and its success d’estime as well as commercial viability confirmed Altman’s status once more.

Altman continued to genre hop through the 1990’s, making a satire on French fashion, a depression era crime story set in Kansas City, a big budget John Grisham legal drama and a film about a gynaecologist and his several women patients. He greeted the new century with another masterful change up with Gosford Park, a British set period piece and the forerunner to the TV smash hit series Downton Abbey. Given Altman’s famous aversion to the TV interpretation of M*A*S*H one wonders what he would have made of the juggernaut the film spawned had he lived? He made one more fine film, the heart-warming and charming A Prairie Home Companion and died unexpectedly in 2006 at the age of 81.

"I look at film as closer to a painting or a piece of music; it's an impression, an impression of character & total atmosphere. The attempt is to enlist an audience emotionally, not intellectually" ~ Robert Altman

Robert Altman was always something of a misfit, struggling to work within the confines of a system that devalued his outsider/maverick ethos. It was not until The American New Wave, or American Renaissance era of movie brat dominated invention came along to reinvigorated American cinema that an auteur like Altman could flourish. The new winds blew away the old Hollywood and suited Altman's aesthetics perfectly where through the 70s particularly he embodied that movement more than anyone, despite the fact he was old enough to be the father of most of the more widely celebrated movie brats. Always at the cutting edge of his own artistic vision he created a compelling and commanding body of work second to none, full of brilliant hits and interesting misses.

also recommended;

Short Cuts

M*A*S*H

3 Women

Gosford Park

Buffalo Bill and the Indians

For fans only;

Images

best avoided:

Pret A Porter