Lang does Renoir (again!)

By Michael Roberts

"It wasn't the way I looked at a man, it was the thought behind it." ~ Gloria Grahame

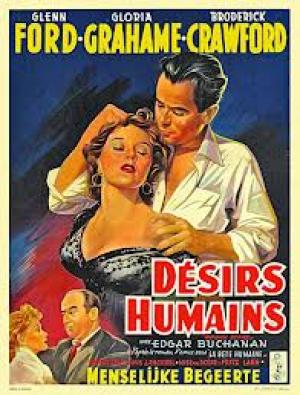

As part of a two picture deal with Harry Cohn at Columbia, the first part of which was the very successful The Big Heat, Fritz Lang followed up with his re-make of Jean Renoir’s La Bête Humaine, from the Emile Zola novel of the same name. Lang again employed his key cast members from The Big Heat, in Glenn Ford and Gloria Grahame, as the illicit lovers, with Columbia contract star Broderick Crawford making up the love triangle. Burnett Guffrey oversaw the noir-tinged photographic palette and made the most of the train yard location shoot and atmospheric surrounds, with Lang contrasting the perennial, interconnecting human relationships with the endless cross country rails upon which his characters travel.

Lang takes the odd choice of opening with a four-minute sequence of dialogue free images, attaching the camera to the front of the train to grab some arresting images of train driver Jeff (Glenn Ford) riding the rails. Jeff disappears into darkness, enveloped by a tunnel, and a foreshadowing of the darkness that is about to envelope him in the form of femme fatale Vicki (Gloria Grahame) and her web of deceit. Vicki is married to a brute of a man in Carl (Broderick Crawford) another rail worker who has a job in administration. Carl unexpectedly loses his job due to his bad temper and he pleads with Vicki to talk to an influential man she knows, Mr Owens, to use his connections to have him re-instated. Vicki does so, but Carl uncovers her dirty secret in the process, and schemes to murder Owens. Jeff is a key witness in the inquest into the incident, and inexplicably lies for Vicki at the hearing, before he's dragged into the conspiracy and into an affair with the temptress.

Lang, or screenwriter Alfred Hayes, make significant changes to the Renoir interpretation, working as they were within the restrictions of the Hollywood studio system and its attendant censorial codes. That said, the decision to make Jeff a decent man, untroubled by the mental illness of Zola's protagonist, does allow for the film to be read as a comment on American society in much the same way Douglas Sirk was doing with his contemporaneous women's melodrama's. Lang may have intuited that Ford did not have the emotional depth of a Jean Gabin, but the script pointed up the darkness in Vicki rather than in Jeff in this version. Jeff, as the American 'everyman' is a Korean War vet, and his life is rolling along in a happy-go-lucky state of comfort, until he sets eyes on Vicki. The battle for Jeff's soul is the central motif of Lang's film, as we are unsure as to his ability to combat the overwhelming desire Vicki has awakened in him.

Douglas Sirk couched his criticisms of American society in slyly coded examinations of the emptiness of the post-war consumerist society, and the emotional vacuum it promoted, i.e. conspicuous consumption can't fill an emotional void. Vicki and Carl, driven by the desire to compete, to have and keep, jealous of people above their social status, are able to commit evil acts to bridge the gap, Vicki with her affair with Owens, and Carl with murder. Jeff is drawn into this dark world, and confronts part of himself that he thought he'd left behind in Korea. 'Is it difficult to kill a man'? Vicki asks Jeff, 'It's the easiest thing in the world', he replies, inadvertently filling her head with possibilities. Jeff's struggle to balance the desire he feels for Vicki with his innate sense of right and wrong is the centre of this film, not so Renoir's, where Lantier is condemned by his compromised blood from the start. Lang, typically with noir, gives Jeff a 'good girl' option, in the daughter of his co-worker, and so conforms to the mores of the time.

The strength of the film lies in Grahame's portrayal of Vicki, one of the best of her significant career. Grahame was no lightweight movie star, and in an era where the vacuous blonde bombshell became a cliché, she delivered with edge and verve many a bloodless portrait of flawed and conniving women. Lang lights her in the expressionist, visual language of a restrained Von Sternberg, suggesting her duplicity with shadow and darkness, as she builds her web for Jeff. Crawford is suitably hard-nosed as the drunken and abusive husband, and Carl's desperation and impotence are equally well rendered by the hulking actor. Ford is called upon to be the straight man, and given the depth he was able to show in his and Lang's The Big Heat from the year before; it's a strange choice that leaves the film slightly out of kilter. Even if Ford did not have the emotional range of a Gabin, one assumes that Lang wanted Ford to play it that way for a reason. I believe it's the emphasis on the femme fatale and her grubby scheme that led him down this path, and it leaves an imperceptible and lingering ambiguity in the final image of Jeff at the wheel of the locomotive, unaware of the carnage and death he has in tow.

Just as Lang had to compromise the suicide ending of The Woman in the Window, here he strays from Zola to deliver a straightforward resolution in favour of good old American values. Where the French could suggest a world of moral ambiguity, Lang had no such luxury, but like Sirk he could shine a light on America's dirty underbelly and suggest that it's mere existence spoke to a wider malaise, one that hinted at unhappiness behind the voracious consumer glut of Eisenhower's 1950s demi-paradise. Lang stayed exclusively in the filmic world of crime and noir during the next few years of his tenure in Hollywood, and they were to be his last before he returned to Germany. His best noir's are the amongst the best of the genre, and while this is not one of them it's a respectable and interesting entry in the cycle. Taken as an expression of dissatisfaction with a culture that promoted possession over everything else, Lang set his monocled eye on the philosophical waste land that he'd found himself in, playing by the rules of the barbarians who ran the game, but reminding us that a fierce intellect was watching, and inviting us to share in the spectacle.