All that money can't buy

By Michael Roberts

“The studio loved the title. They thought it meant you could have everything you wanted. I meant it exactly the other way ‘round. As far as I am concerned, heaven is stingy." ~ Douglas Sirk

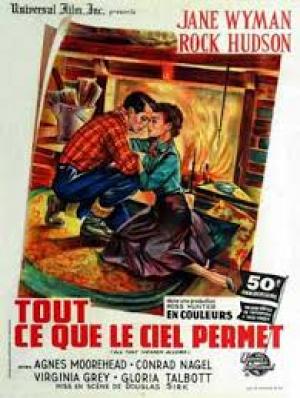

After being championed by Robert Siodmak to effectively replace him as house director at Universal in the early 1950’s, Douglas Sirk set to work applying his cultured eye to a succession of American entertainment staples. He made a series of more than competent comedies, musicals and even westerns (really!) before he found his metier in a series of stunning films that essayed America’s hollow middle-class, consumerist values, only to have them grossly misunderstood and initially derided as ‘woman’s pictures’. Prime amongst his ‘woman’s pictures’ is All That Heaven Allows, a gloriously glossy dissection of prejudice and social mores masquerading as a relationship soap opera, starring Universal heart-throb Rock Hudson (who knew a thing or two about masquerades) and Jane Wyman, a woman past her Hollywood prime but still a drawcard on the billing. Furthermore, and crucially for Sirk, he was left alone by Universal as long as he stuck to his budget and the rules of 1950's melodrama, like the obligatory happy ending.

Cary Scott (Jane Wyman) is a wealthy New England widow, negotiating an outwardly perfect life amongst her peers and college-aged children. She strikes up an unlikely relationship with Ron Kirby (Rock Hudson), a handsome young gardener from a lower social class and as their attraction deepens certain hurdles are thrown up by Cary’s family and friends. Cary buckles to this societal pressure in ending the liaison but the lovers suffer terribly for the decision in various ways before a tragic accident reunites them.

Universal were well pleased with the teaming of producer Ross Hunter and Sirk and of the success of their previous film, the Hudson-Wyman fronted ‘weepie’, Magnificent Obsession. Universal asked that the actors be re-teamed and upped the budget available for the next outing, giving Sirk more scope for realising his cinematic vision. In tandem with the brilliant Russell Metty as cinematographer, who made a total of 10 full features with Sirk, the emboldened director pushed his elaborate colour schemes and deliberate ironic flourishes into the source material until the very exaggerations pushed the project beyond the tawdry trashiness usually associated with the form and into the realm of art. Within the first 10 minutes Sirk has invoked both Freud (“When we reach a certain age sex becomes incongruous”) and classical antiquity burial rituals (the Egyptian practice of walling up a live widow in her dead husband’s tomb) in a loaded mother-daughter dialogue – all this set in a storybook beautiful setting where even the trees don’t have a leaf out of place!

If Hitchcock was able to employ a heightened reality by constructing deliberately artificial sets, then Sirk goes even further. The artifice is code for the fake-ness at the heart of the relationships in the idealised small town. Even the town’s name takes of significance, Stoningham, where a scandalised woman is ‘stoned’ by her peers in a metaphorical sense for having the effrontery to show off the object of her base desires in public. Prior to striking up a relationship with Ron Cary had been doomed to fend off the boozy advances of her friend’s husbands or be expected to be satisfied with “companionship and affection”, in effect a life of Thoreau’s “quiet desperation.” To relieve her loneliness, her children buy Cary a television for Christmas, in which Sirk shows her reflected image, effectively imprisoned by the device, a modern tomb.

After the war American industry re-tooled their war machine to produce a consumer society that accounted for 60% of the world’s consumption of consumer goods. The economy boomed as average wages multiplied 5 to 6 times in 15 years between 1945 and 1960, producing an affluent middle class. The counter to this prosperity was the fear of losing those gains, exploited by a Cold War/McCarthy era backlash against suspected Communist influence in several areas of American life, including Hollywood. Incredibly, Sirk had to answer FBI questions about an ‘anti-corporation’ angle in his 1952 Tony Curtis comedy, No Room For The Groom, and maybe that led him to ‘smuggling’ his subversive idea’s about American life into his later films. It also must be pointed out that Sirk is scathing in examining the mores and rituals of the society, not of the people conditioned by their culture to behave as they do – his affection for ordinary American people is obvious in the scenes with Ron’s friends.

In this consumerist society, Cary is a possession, and the argument amongst her friends and family is essentially about who gets to possess her now she’s a widow. Cary’s own desire is never taken into account, as evidenced by the conversation she has with her bookworm daughter regarding marriage, where the emotional/intellectual divide towards the institution is highlighted. The daughter announces her impending marriage, oblivious to the hurt she causes her mother, whose marriage she had previously joined in stymying. The son has barely concealed Oedipus issues and when Cary puts on a red dress to go to a party her son objects. Sirk treats Cary like the damaged Wedgewood vase she picks up at Ron’s – a damaged but beautiful object in need of repair by loving attention. Ron provides the attention to have Cary blossom like one of his trees and shows Cary an authentic alternative to her sterile existence, where she also finds warmth and easy comraderies amongst his friends. Sirk employs a final visual grace note to indicate Cary’s relationship to beauty, freedom and cages, ideas that permeate the entire piece.

Douglas Sirk continued his mentor/father-figure association with Rock Hudson, an actor of limited range with whom he made nine films in total, their previous collaboration, Magnificent Obsession, making Hudson a bona-fide movie star. Sirk used Wyman brilliantly, allowing her an understated, acerbic throw away lines like her response to her daughter’s declaration that they don’t bury widows anymore, “Don’t they? Maybe not in Egypt.” It sums up the entire theme of the film in 6 words. Sirk also used the marvellous Agnes Moorehead and Jacqueline De Wit, both excellent as the proto-Stepford friends caught in a cycle of barely supressed jealousy and envy as they set about cutting Cary down to size.

All That Heaven Allows is also a sly repudiation of the myth of the classless society in America as not only is Ron below Cary’s social station, he’s not vaguely interested in making money for the sake of it or social climbing, a startling idea in the home of capitalism in the 1950’s. The film is a masterwork from Sirk on many levels, dismissed at the time but now embraced by feminists and cineastes alike, but it mostly remains a subtle indictment of the American Dream and a reminder that in the midst of the biggest consumerist binge in the history of the world, there was abject emptiness at its rotten core.

All That Heaven Allows was a key film in the re-evaluation of Douglas Sirk’s critical legacy after Jon Halliday’s book, Sirk on Sirk in 1970 and with German iconoclast Rainer Werner Fassbinder, who embraced Sirk’s aesthetic with his seminal Ali: Fear Eats The Soul in 1974. Now revered as a master of mise-en-scène and irony, his influence and reputation ensured, Sirk was notably paid tribute by Todd Haynes with his superb melodrama Far From Heaven in 2002 as the ripples of his artistry continues to spread.

“This is the dialectic—there is a very short distance between high art and trash, and trash that contains an element of craziness is by this very quality nearer to art.” ~ Douglas Sirk