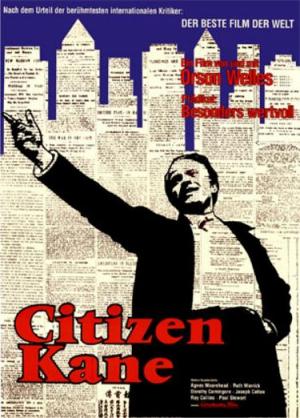

The mark of Kane

By Michael Roberts

“A writer needs a pen, an artist needs a brush, but a filmmaker needs an army.” ~ Orson Welles

Orson Welles had built such a reputation as the master of the entertainment mediums of stage and radio in the late 1930s, that when he turned his ambitions to film RKO gave him the keys to the lolly shop and let him loose. Welles attempted writing and pre-production to varying degrees on several properties, notably Smiler With A Knife and Conrad's Heart of Darkness but had problems with all of them before settling on an idea cooked up by himself and Herman Mankiewicz. After rejecting Howard Hughes as the model of a successful man who falls because of personal flaws they decided on a publisher, as both men had connections to the William Randolph Hearst clique. Welles' first wife was now attached to Marion Davies' nephew and was a constant guest at Hearst Castle, whereas Mankiewicz was a former regular there who became persona non grata after his heavy drinking garnered disapproval from the hosts. Mankiewicz was well placed as a former insider to add authority to any script conforming to Welles' 'great man' theory of history, and a script with the title of American was knocked into shape by the two men and producer John Houseman.

Welles tells the story of Charles Foster Kane in complicated, (for the time) fractured flashbacks, anticipating Rashomon by many years, and book-ends the tale with a sign that reads 'No trespassing', an ironic comment on a publishing magnate who saw no boundaries between the private or the public in gathering material to sell newspapers. The famous device of having a death bed utterance from Kane lead to a kind of search for what the word 'Rosebud' represented to him gave Welles a roving commission in what he could examine, freeing him to let his fertile mind unleash it's many vivid imaginings. He employed many of his Mercury Theatre stage actors in central roles, and the largely unknown nature of their faces brought a freshness and zest to the proceedings. Joseph Cotton showed he was a solid performer as Jed Leland, Kane's only real friend, and Everett Sloane did well as Bernstein, Kane's business manager. The women who play Kane's wife and mistress are both fine, with Dorothy Comingore as Susan the inept Grand Opera 'singer' particularly good, but it's Welles' portrayal of Kane that dominates proceedings, aging from a handsome mid '20s to near 70 and on screen for a large part of the running time. Welles is dynamic, brave and commanding and proved he could have had a career as an actor in all else failed.

Welles had the great good fortune to literally bump into Gregg Toland, fresh from winning an Oscar for cinematography, who liked the idea of working with a first time director and he actively sought Welles out. Toland was especially keen on one as imaginative and inquisitive as Welles and signed on to create one of the most visually stunning and innovative pieces of cinema ever made. Welles sought out a visual language in the same way he'd fallen in love with the written word, testing and probing for effect, and never quite placing his camera where other less adventurous director's would, this would become a trademark throughout his career. Welles uses a lot of his radio skills in the way he shaped the sound of the film, pushing sound design ahead in quantum leaps with his incorporating of all elements. He brought his regular radio composer Bernard Herrmann out from New York to score the film, and Herrmann famously went on to close and significant collaborations with Hitchcock, and carved out a distinguished career as a film composer until the mid 1970's.

Welles creates a brilliant faux newsreel called 'News On The March' to flesh out the details of the life of the media tycoon to whom death came 'as it must to all men'. The detail and techniques in that segment alone dwarfed most contemporary films. Welles examines a man who has it all, in a consumerist capitalist sense, but who has no values other than self absorption, no depth with which to withstand the corrupting influence of enormous power. Kane starts out as a newspaper man from motives of spite, 'it might be fun to run a newspaper', but he really wants to turn its potential against the institutional interests his guardian Thatcher (George Coulouris) represents. Kane was sent to live with Thatcher as a boy, uprooted from his countryside idyll by an ambitious mother, but resents the loss of his childhood more than anything and despises the Wall Street ethos of Thatcher and his ilk. Kane is enamored of his new influence as a crusading editor and writes a 'Declaration of principles' setting out his interest in delivering 'honest' news for the common man, a champion of the working class, "I always gagged on that silver spoon", but part of Kane's tragedy is that he doesn't belong to the patrician class to which he was exiled, or to the 'beloved' working class for whom he sees himself as defender in chief. Leland says of Kane, "He was disappointed in the world so he built one of his own".

Kane's flaw is his blind spot in relation to love, he is incapable of true connection with another because the love he demands is on his terms only, and those terms are as uncompromising as his appetite to 'collect' things is. Kane thinks he who dies with the most wins, and love is to be collected and catalogued along with his other possessions. Jed says it as, "He never believed in anything except Charlie Kane", and even threw the 'Declaration of principles' back at him once he thought he'd betrayed them. Kane was trying to convince himself as much as Jed and Bernstein that he actually believed in them, but ultimately Kane's narcissism trumped any need to pretend otherwise. Unable to be truly happy Kane is only able to yearn for a simpler time when life was uncomplicated, when he gambols in the snow in Colorado within the caring warmth of his mother's love, hence 'Rosebud'. Gore Vidal seems to have been the one to entrench the rumour that 'Rosebud' was Hearst's pet name for Marion Davies' clitoris, but there's no evidence to suggest the writers ever admitted this. The cut from the newspaper men sent on the trail of what 'Rosebud' means is suggestive though, after the line "it will probably turn out to be a very simple thing", Welles makes a sharp cut to the face of Susan on a poster, looking all the world like Marion Davies. One imagines if it was the case Hearst would have hit the roof at that point.... and maybe that's half the fun to speculate?

Welles' visual eye and instincts, honed in a theatre world, took wings with the potential cinema offered. Toland's deep focus photography let Welles compose frames that were full of interest and meaning, adding to the narrative flow and support. Welles frames Kane's younger self in the background playing in the snow through a window, while his mother signs away his future. He later re-incorporates the idea when Kane is again in the background through a door, when in the foreground Thatcher is again signing documents that take a level of control of his life away from him, something he despises. Welles displayed an ability to 'excite' a scene with flair and taste, e.g. whereas another director of the era filming an interview scene with a character behind a desk would settle on a pedestrian two shot set up, Welles favoured a single shot and long take that didn't reveal the interviewer directly and a deep reflection in the polished desk that gives the scene another dimension, essentially the difference between plain photography and art. Welles shows the decay of Kane's marriage through a series of breakfast table vignettes over the course of many years, giving detail and clarity with ease and sleight of hand, informing and entertaining with great deftness. Welles mastered the language of film in his first attempt, progressing the medium and adding to its vocabulary in the most meaningful way since Griffith over 20 years before.

Kane's hubris undoes him, and maybe Welles saw something of himself in that? Kane professed a love for the 'people', but as Jed pointed out "you talk of the people as though you own them"? Kane never understood that money could not buy everything, not love, not respect and his patrician, condescending view of the 'working class' is also challenged by Jed when he warns that they are organising and he might not like the results. Ironically in the newsreel section Kane the capitalist is accused of being a 'communist' a 'fascist', before he himself uses the descriptor American. It's also ironic that it's a lowly worker who destroys Rosebud at the end, tossing the symbol of Kane's happy youth into the fire.

That Orson Welles should make a film about a control freak is not surprising, but for him to create such a masterpiece with his debut feature is a thing to marvel at. The Hearst press did their best to destroy and suppress the film, but in the end its quality ensured that enough people bucked the trend and championed its cause. The film lost a small amount of money and even though it was nominated for 11 Academy Awards, it only won two, Hollywood was not about to fall at the feet of the 'boy wonder' who pissed off Hearst. Hollywood soon made damn sure that a phenomenon like Welles would never happen again, and the dream contract he had with RKO dissolved in a puff of smoke, as they changed management, defamed him to the press by calling him profligate and re-cut his second feature The Magnificent Ambersons to the point Welles more or less disowned it. After all the fuss, after all the hype, the timeless masterpiece that is Citizen Kane endures and much of the language of modern cinema starts here.