Birth of a nation

By Michael Roberts

“War does not determine who is right - only who is left.”

~ Bertrand Russell

With the frenzy and near rabid patriotic fervour reaching a fever pitch in Australia on the 100th anniversary of the disastrous British campaign in Turkey in 1915, it’s revealing to look back at Peter Wier’s Gallipoli, a film that has much added to the ANZAC myth. It’s also worthwhile to recall that the Turks lost ten times as many men as the Australians in defending their homeland from invaders bent on their destruction, and also that the Australians made up little more than 10 per cent of the Imperial troops. The Dardanelles campaign was the folly of a younger Winston Churchill and as bitter as the Australians were at the extent of the carnage it is certain that the British soldiers who died there were done no favours by their incompetent generals either.

Australians regard the WWI campaign at Gallipoli as the pre-eminent event in the countries forming of its national identity, ironically in a British war on the other side of the world. We may be one of the only countries in the world that has managed to eulogise a military defeat and turn it into legend, an enduring myth that speaks of a nation unsure of its identity, until it proved itself on the killing fields of Turkey. Peter Weir took aim at that national myth in this film and he commissioned famous playwright David Williamson to script it based on his outline in the decade leading up to Australia's celebration of 200 years of white settlement, investigating what it meant to our modern sense of national identity. Williamson, perhaps wisely, set a lot of the film's duration in Western Australia and focuses on the conditions at home; only in the last 20% of the running time does he locate the action on the peninsula south of the Dardanelles. Weir cast rising young American born, but Australian trained actor Mel Gibson in the role of Frank, and an unknown actor in the role of Archie, Mark Lee, the two friends who set off to war.

Weir opens with a young runner, Archie (Mark Lee) being coached by his Uncle (Bill Kerr), and training for a big regional track meet in May 1915. The talk among young men at a cattle round up in the outback is of the war in Europe, despite his friend's urgings that "girls go wild for a uniform", Frank (Mel Gibson) declares he won't join up. Frank is a runner with a reputation and puts 20 pounds on himself to win the race at the local Show, the same race Archie enters. Archie beats Frank but the two become friends, and Archie determines to go to Perth to join up, Frank tags along. Archie tries to convince Frank to join up with him, but Frank is of Irish descent and old wounds die hard, "It's not our war, it's an English war" he replies. The boys bond and eventually feelings of mateship win out and Frank joins up, but he and Archie split up, one to the Infantry and the other to Cavalry as both end up in Egypt for training. The pair eventually convinces a senior officer to assign them both to the same division and they embark for Gallipoli.

The idea of 'mateship' is the holy central tenet of Australian male culture, and the events surrounding the 'trial by fire' that the Great War symbolised have been a key plank in that dominant meme. Young Australian males died in droves during that conflict, and at some point a positive spin was needed to convince the country that the blood sacrifice was worth the price paid. The idyllic, if dull, home life that the young men of rural Australia led seemed tame in comparison to what the excitement of a foreign war offered, and Australia answered recruitment drives in huge numbers. It was not until the death toll mounted after a couple of years of slaughter that the question of conscription arose, but it was twice defeated in a referendum plebiscite. The vast expanses of nothingness on the continent and the laconic Australian character collides at the point young Archie is asked by a wandering Swaggie why he would sign up to fight Germans over there?, Archie tells him "otherwise they'd be coming here", to which the old man takes a lingering look at the miles of surrounding desolation and laconically replies, "and they're welcome to it".

* In an amazing aside, when the Brits enacted the Balfour Act after WWI to establish a Jewish homeland, they drew up a shortlist of locations, and one of the top contenders (along with Palestine) was Western Australia! If only they'd taken a slice of WA, history would be so different. Israel isn't as big as some outback sheep or cattle stations, and there are no Arabs. The indigenous population were not a consideration in 1919, sadly.

Australia had only become an independent country a dozen or so years prior to Gallipoli, and most of the populace would have still identified as 'British'. The yen to 'prove' ourselves as a country was part of the impetus for so many men to sign on and sail away, but it left a hole of 60,000 dead and twice that wounded, from the flower of the young nation's manhood. The 'received' history at the time Williamson wrote, and an angle that appealed to the recalcitrant, or 'larrikin' side of the national character, was that the Australian boys were 'sold out' by the incompetent English officers. There is no evidence for this, and the Australian officers as well as the English exhibited plenty of incompetence, and nobody suffered more than the English Tommies of the death beaches of the peninsula. The scene where the English are sipping tea on Suvla Bay while the Aussies are being shot to pieces did not happen, even though the battles were as chaotic and as poorly thought through as anything on the Western Front . The campaign and the wisdom of Churchill's folly are questionable, but the central fact was the Turks were fighting for their homeland, and the strategists on the British side underestimated their ability and resolve. (Big shout out to Ukraine!)

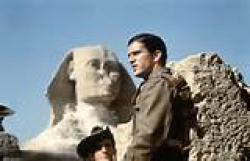

Weir recreates the early 20th century country ambience with great detail and care, as he had done in his previous film, Picnic at Hanging Rock. Aided by wonderful performances from his leads, particularly in Gibson who marked himself as a star right away, Weir fashioned a stylish and mature work that captures every available nuance of the compelling narrative. The Egyptian scenes are superb, and the sight of Australians playing our national code of Aussie Rules football under the shade of the great pyramids is priceless. Weir captures the humour and the cheekiness of the Australian foot soldiers, greatly disliked by the British officer class. One of the reasons for this was the Australians, alone out of all the Empire soldiers, did not have capital punishment for insubordination. Australians led several 'mutinies' on the Western Front, against what they thought of as unfair or unreasonable instructions, which would have had them shot otherwise.

The myth of ANZAC and the pull of Gallipoli won’t go away anytime soon, but when the welter of fuss on the 100th anniversary fades it might be that we look at the mighty effort Australia made in France, particularly in the latter stages of the war, to get a wider perspective on that ghastly conflict and the national cost. Peter Weir created a timeless classic with Gallipoli, a film that lives up to the lofty ambitions of its title (are you listening Baz Lurhman?) and evokes all the pointlessness of that awful war, but with enough heart and empathy for the men caught in the middle. The film was produced by impresario Robert Stigwood, and publisher Rupert Murdoch, whose father Sir Keith Murdoch was a famous war correspondent at the time. If only Rupert’s legacy was limited to this gem.