Timeless and eternal

By Michael Roberts

'I never thought of becoming a director. When I was twelve, the passage from silent film to the talkies had an impact on me - I still watch silent films.'

~ Alain Renais

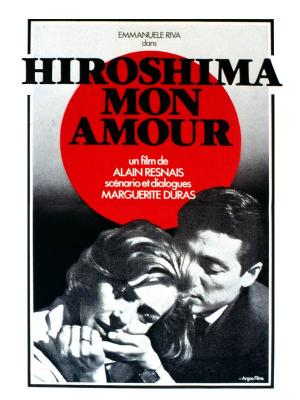

Of the three films from 1959 generally accepted as the markers for the start of a collectively known era called Nouvelle Vague it might be said that Truffaut’s 400 Blows was raw and humanist, Godard’s Breathless was brash and daring and Hiroshima, Mon Amour, the boldest of them all, was simply transcendent. Alain Renais made a film that works on the level of great music, unlocking a transportative power that acts upon a deeper part of our psyche where the effect is largely mystical, almost beyond intellect. Renais collaborated with screenwriter and novelist Marguerite Duras, who evoked a youthful affair of her own with a Chinese man in the intensity and honesty of the love scenes, and together they meld both the documentary and the narrative aspects into a greater whole creating, via a motif of ‘memory’, something beautiful and eternal.

The arresting opening close ups of the two lovers sets the dimensions we can expect, the bodies are indistinguishable and their parts unidentifiable as to who belongs to what, a perfect fusion of lighting and mood and music, sweating, shimmering bodies dissolving into one entity. In a voice-over of internal dialogue we hear the woman dealing with what she’s seen since she’s been in Hiroshima, inter-cut with images of the aftermath of the atomic bombing of the city 14 years earlier. The voice-over opens into a conversation between the man and the woman, recalling events that led to the bedroom. The first 15 minutes of the film is dedicated to this form, a montage of images and a series of dissections on the nature of remembering, ‘I met you’, ‘I remember you’, ‘who are you’? being part of the lyrical and emotional dance the two are entwined in. In the symbolic city they are in remembrance is ubiquitous, it’s especially important to remember, but that throws up issues of the nature of memory, and of the control of that nature.

The film opens out into the narrative portion and we discover the woman (Emmanuelle Riva) is a French actress in town making a film ‘about peace’ and is leaving the next day for Paris. The man (Elji Okada) is a Japanese architect and the two engage in contemplating her situation where ‘staying is even more impossible than leaving’. The architect visits her on set, hoping to convince her to stay, they have opened up to each other physically and emotionally and it’s hard for either to go back to a ‘normal’ life. He discovers she spent the war years in her home town of Nevers, whereas he was in the army when the bomb was dropped on his home town, killing his family. memories of Nevers start to intrude on her present and via a progressively more complex series of flashbacks we learn she is recalling her first impossible love, that of a young German soldier during the occupation. The architect takes her home, ‘where is your wife’? she remarks, as he reveals he’s ‘happily married’, ‘so am I’, she replies. After making love again they go out to restaurant and the memories of the war for her get darker and more intense as she reveals that the soldier was killed the day the allies liberated the town, and afterwards she had her head shaven as the mark of a collaborator. The actress recalls her mental breakdown, how she was ‘as dead as his body’, the young girl who dies of love in Nevers.

She leaves the architect and strolls the streets of Hiroshima, confused and conflicted at what has been stirred up by this affair, confronting the ‘horror of forgetting’ and as lost as when she left her home for Paris to forget her dead love. He finds her and she admits that she’d never even told her husband her story, ‘I cheated on you tonight, and told our story’, she directs her thoughts to her dead lover, as if she’s given away a sacred confidence. It’s only in confronting a traumatic past that a bearable future is possible and the actress says to the young version of herself ‘I relinquish you to oblivion’, just as she knows she must do to the memory of the architect. ’I’m forgetting you already’, she says as the inevitable farewell descends. The architect can only wonder at the universality of l’amour fou, his declaration that ‘the world celebrated’ the destruction of his home town has resonance now at the personal level of the private disasters experienced at the same time on the other side of the world. Politics is infused in every frame with the directness of the documentary footage, yet never really directly addressed - there is a peace rally that the couple get caught up in, an ironic commentary on the arms race of the late ’50s. Plus ca change. What is tacit here is the question ‘at what cost did we inflict the personal tragedies of Hiroshima’? War decimating on the macro as well as the micro scale, the universality of suffering, as well as impossible love.

Emmanuelle Riva is superb in generating the reservoirs of feeling needed for such a demanding role, and after coming to film from a stage background she worked only very sporadically in cinema, never again taking such a strong leading part, until her startling and welcome return in Michael Haneke's revelatory look at old age in 2012's Amour. The score from Georges Delerue is stunning, abetted by Antonioni collaborator Giovanni Fusco. Dumas, from the tradition of the Nouvelle Roman, writes poetically and expressively of the ways we can die inside well before our body expires. Renais invests the visuals with a formality more in keeping with the classicists than his contemporaries, but in the non-linear construction and the existential overlay he gets into territory that is entirely his own. He would further stretch these boundaries of memory and sense in the his next film Last year in Marienbad, and with another Novelle Roman writer Robbe-Grillet. The tenor of Hiroshima, Mon Amour had its antecedents in more mundane considerations, ie, the production company needed to cast a Japanese and a French lead to satisfy the international investors, also it was commissioned as a documentary, but when Renais hit a wall saying he felt the definitive Hiroshima doco’s had already been made, the producer suggested he work with Marguerite Duras, and Renais jumped at the chance, her love story taking the documentary and giving it another dimension. From such accidents alchemy happens.

Eric Rohmer called it the first modern film and maybe it is, as modern as tomorrow and as timeless as yesterday, It belongs to the ages.