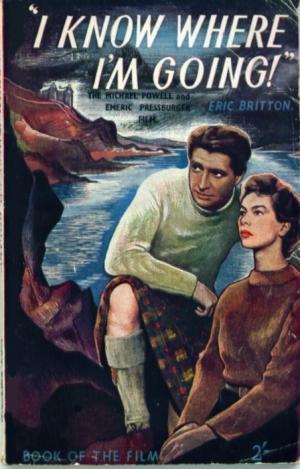

A Scot's valentine

By Michael Roberts

'Art is merciless observation, sympathy, imagination, and a sense of detachment that is almost cruelty.'

~ Michael Powell

Michael Powell has a legitimate claim to be the greatest of the classic British directors. He certainly stands up alongside Hitchcock, Reed and Lean, and it’s because of great films like this. In many ways it’s one of his most accessible creations due to the universality and simplicity of the story, of unexpected love in an unexpected place. The theme that nothing is greater than the power of love is one Powell and his partner Emeric Pressburger will return to many times in their careers, and it was to dominate this black and white film, as colour stock was in short supply during the war, and their next Technicolor marvel A Matter Of Life And Death.

It oozes charm from start to finish, thanks to the stunning location and beautiful performances. Joan Webster (Wendy Hiller) is a woman on a mission, and she has organised her schedule to the second to accomplish it, leaving no room for serendipity in the process. She is bent on marrying into Scottish landed gentry, a Sir Robert Bellinger to be exact, a millionaire industrialist whose company is manufacturing chemicals profitably for the war machine ,and duly sets off by train from London to the wild Hebrides Islands in the north to marry the much older man. Powell barely shows us her intended and he remains as much an aside or a myth and also symbol of what the capitalist side of the war years represented, remoteness and a disconnection from what was happening ‘on the ground’. Joan is within an ace of achieving her aim, all her carefully laid plans running like clockwork, when mother nature intervenes and prevents her from completing the final leg. Her intended lives on Kiloran and the island is inaccessible in bad weather, no boatman will take her across. She’s forced to cool her heels in local accommodation arranged by a kindly naval officer on leave Torquil MacNeil (Roger Livesey). Torquil presses his friend Catriona (Pamela Brown) into putting up lodging’s so that Joan can wait out the weather. Powell throws in Scottish mythology in the form of stories of an ancient curse on the Laird of Kiloran, who Joan thinks is her fiance, but turns out to be Torquil who is leasing his land to Bellinger.

Joan gets to know a different world from the one she thought she was embracing, in fact Joan is faced with real people, intruding into what was to be her fairy tale life. As often happened in the war years when two people are thrown together by circumstance and the attraction is undeniable, love blossoms. Joan realises she won’t be able to hold out against fate and becomes more desperate to make the crossing, running away from reality and Torquil. Catriona by her sheer vitality and independent behaviour forces her to reassess her idea of what constitutes a ‘modern woman’, and to see the kind of stultifying future that awaits her if she manages to get across to Kiloran. Joan bribes a young fisherman to take her across in bad weather and Torquil insists on going for their safety. The engine is drowned and the powerless boat is sucked towards the maelstrom, it’s turbulence a metaphor for the emotions swirling about in Joan. Torquil saves the boat but cedes Joan to Kiloran and Bellinger, but she rejects that future and in lifting an ancient curse on its Laird she walks into Torquil’s arms.

I Know Where I'm Going is a film of contrasts - the antidote to what Joan thinks she wants, i.e, buying into the establishment to secure her future, appears in the form of an earthy naval officer played by Roger Livesy, ironically the traditional owner of the land. He’s been forced into leasing it out, dispossessed by the system she aspires to, but continues to risk his life in its war. An amazingly modern woman, played by Pamela Brown, is the contrasting female character to Hiller’s ‘proper lady’ type. Brown comes into the picture as a force of nature, a female the equal or easily the better of most of the men about, and causes the becalmed Hiller to reflect upon her mores and preconceptions, indeed of the very roles of men and women.

From this confection Powell spins his magic. It’s hard to imagine a more charming fable, or a more winning realisation. It’s a valentine to the Scottish locations that Powell loved and the fact that Livesy actually never set foot in Scotland is a seamless conceit. Livesy was contracted to a Peter Ustinov hit play on London’s West-End and did all his work in a London studio at Denham. Also evident is Powell’s deep feeling for the Scottish people, especially in his use of Finlay Currie and John Laurie, friends from his 1937 breakthrough film The Edge Of The World, also set in the wild Scottish Isles. The lead was originally cast with James Mason, but Powell and he had a falling out and it was 26 years later that they finally worked together in the underrated Age Of Consent. Powell was also something of a ladies man, having bedded his star from Colonel Blimp, Deborah Kerr (whom he desperately wanted to cast as Joan) but personal circumstances forbade, and so cast Hiller, who had ironically missed out on Blimp, and he began an affair with Pamela Brown* on this film that lasted many years. Brown was so vibrant and magnetic in her supporting role it’s hard to believe she was chronically arthritic, to the point she took the infamous ‘gold treatment’, where extracted chemical compounds of gold are actually injected into patients veins! Who needs an Oscar?!

The social themes are never intrusive and weave nicely as a sub text of reality in what would be an otherwise sugary fable. Joan rejects the ‘landowner’ for the true ‘owner of the land’, a man who is not squatting as an interloper but is historically connected and bound to the earth in a more organic way. Joan resorts to her own mysticism in trying to clear the obstacles in her way, prayer, but nature will have none of it and won’t be controlled by her incantations. Nature hurls her plea’s back at her in spades during the fraught sea crossing and only Torquil has the grace needed to extract her from danger and enable to see her true self, the one she’s denied for so long.

In perfect black and white and expertly shot by Erwin Hillier, who also worked on the Archers magnificent A Canterbury Tale, it captured and distilled so much more than its modest scenario promised. Powell brings a beautiful summation of love to a war weary audience and cajoles several fine performances from a wonderful cast in doing so. It’s a sweet dream of a movie.

* Some years back I met Powell's niece Cornelia Francis, (an actress in Australia) a few times, and asked her about the film. I should have remembered she was his niece from his wife's Frankie's side because she fairly spat out her opinion - 'That film! That's the one where Uncle Micky ran off with that slut Pamela Brown!' Ouch.