Capote fiction-fact

By Michael Roberts

'First comes the word.' ~ Richard Brooks (engraved on his tombstone)

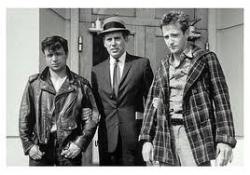

Richard Brooks’ adaptation of Capote’s true-crime masterpiece In Cold Blood is a compelling and authentic examination of the consequences of a lack of empathy in societies marginalised and disenfranchised, represented by Perry Smith and Dick Hickock. America, at the near end of the ’50s, was in the middle of the biggest consumer boom in history, fuelled by the increased production capacity World War II unlocked, the cashed up middle class and the evolution of suburbia it represented fully 40% of the world’s product consumption. Coming like an H bomb into this paradisiacal orgy of Madison Avenue cheer-led consumerism was the horrific multiple murder of a respected, conservative farming family in Kansas, rocking the country to its core and challenging its deepest held values. The killers are a twin headed monster from the Id, arising in blackest night and killing for seemingly no reason, disturbing the fabric of a complacent and ascendant country, the actual reason when it was uncovered should have come as no surprise, and it was simply money, honey. Brooks resisted the studio overtures to cast Steve McQueen and Paul Newman as the leads, and kept the low key and downbeat tones of the novel intact, making a near documentary, rural-noir in the process that avoids falling into becoming purely a police procedural and allows us to see the brutal ‘ordinariness’ of the protagonists, the most scary aspect of the entire piece. Truman Capote, interested in finding a subject he could turn into a ‘nonfiction novel’, travelled to Kansas soon after the events and spent the next 5 years researching the crime, assisted by friend and author Harper Lee, he interviewed the two killers and appears to have struck up a particularly close relationship with Smith. The book is dimensional and non-didactic, and the film remains true to Capote’s vision to a remarkable degree.

Brooks opens with two of the strongest elements of his film to the fore, the music from Quincy Jones, wrapped around the stunning cinematography from Conrad Hall, as Smith (Robert Blake) is found riding a Greyhound to Kansas to rendezvous with Hickock (Scott Wilson) the expressionist lighting creating a noir mood and a close up on the heels of Smith’s boots a foreshadowing of what will eventually incriminate the pair and lead to their conviction. Dick is first seen like a hunter preparing for a shoot, and the Clutter’s are seen with some bucolic music underscoring the peaceful environment that will soon be shattered forever. Perry indulges in a fantasy that he’s a famous singer in Vegas, before Dick intrudes and leads him though the plan for the robbery. Dick informs Perry there’s ‘one law for the rich and one for the poor’ and that they will be leaving no witnesses after collecting the $10,000 that his prison cellmate assured him Clutter kept in his safe. Clutter signs a double indemnity insurance policy, the ‘solemn moment’ as the salesman poetically puts it, thereby linking the value of a man’s life inextricably to money, in the same way that Perry will reduce it to a mere $43, the actual haul. Likening their partnership to a marriage ‘til death do us part’, the unholy alliance proceed with a ghastly inevitability to their destination, and Perry has second thoughts. Dick lets him know that he picked him because he’s a ‘natural born killer’ , having fallen for the fabulist tale Perry had earlier spun about killing a man in Vegas. They pull up at the house in the middle of the night.

Brooks cuts to the next day and the discovery of the bodies and the engagement of the law enforcement officers, primarily Alvin Dewey (John Forsythe). The police have almost nothing to go on and apart from the footprint in blood they have no leads. Unremarkably the criminals are given up by Floyd Wells, the in-mate who told Dick of the fictional safe at the Clutter house, he informs on Dick and the law closes in. The boys went to Mexico but soon run out of money and end up back in Vegas passing bad cheques. A lovely vignette with a boy and an old man collecting bottles worth 3 cents each upon refund is the only relief in a journey where the ultimate end is as bleak as their non-descript existence. The police make short work out of getting confessions as luckily they picked the pair up after they’d collected their belongings that they’d sent from Mexico, which included the incriminating boots, otherwise the confessions would not have come and the case would have not gone to court. Perry recalls the crime in detail, and the matter-of-fact way the family are disposed of after it’s apparent that there was no safe to rob. Perry also relates how he stopped Dick from raping the daughter ‘I despise people who can’t control themselves’. He professes admiration for Mr Clutter ‘He was a very nice man, I thought so right up until the time I cut his throat’. The men spend 5 years on death row, until in a bravura sequence of editing and tension, the gallows claims them both. When told by a reporter in relation to capital punishment that, ‘Maybe this will help’, Jensen the writer who represents Capote replies ‘It never has’. Psychologically the motivation is speculated upon by many of the stakeholders, and at one point it’s alleged that neither could have acted alone, and that together they created a third person who took over and did the deed. Perry says at one point ’There’s got to be something wrong with us to do what we did’? Perry earlier related a tale of how a yellow bird had come down and rescued him from the nuns at the orphanage, his fantasy saviour was not sighted from the platform of the Kansas state prison.

The two leads are never less than superb, in completely un-movie star performances they engage in ways that remind us of a Bresson or Italian Neo-Realist ‘actor’. Startlingly Brooks uses some of the people who were involved in the actual case, locals in the actual town where he filmed on location, and the jury too! Incredibly he used the actual Clutter house for filming, and even the actual hangman! Simpler times maybe? Bizarrely, Perry was very fond of the Bogart movie Treasure of the Sierra Madre and mentions it in the book as motivation to go to Mexico, so when Robert Blake is referencing it in the film, it feels like an ‘in-joke’ as serendipitously Blake played the shoe-shine boy in the film as a child who shines John Huston’s shoes. What are the odds?!

The case was a seminal one in America, scarring the nation in many ways and causing middle-America to ask ’who’s safe anymore’? In an era where America had thought of itself as the ‘promised land’ where opportunity and growth seemingly had no limit, where it was the good guy in a life and death struggle with the evil Soviet’s for superpower dominance, this was a reminder of what evil can lurk in a dark heart. A society can only function if it does not actively disenfranchise huge swathes of its population, otherwise history suggest there will be significant blowback, killers like Perry and Dick are not made in a vacuum. America’s prisons continue to bulge at a level disproportionate to any other comparable western country. The promised land? for some maybe.

Brooks' film is as timeless and apposite today (1/4 way into 21st century) as when it was filmed as America struggles with the wild west, gun culture ripples that still infect its communities. Killers like Perry and Dick were classic 'failed joiners' looking to be noticed by a society who dismissed and marginalised them. Their inheritors fronted up at Columbine, Colorado, Sandy Hook, Oregon, Parkland, Santa Fe, Uvalde...... (fill in blank)......