Silent night, silent guns

By Michael Roberts

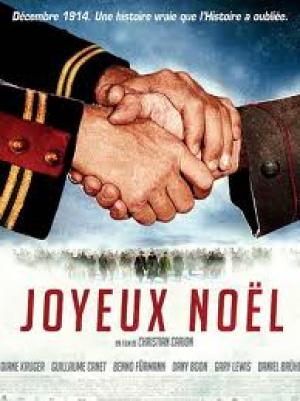

Christian Carion used a little known World War 1 event to create a powerful reminder of shared humanity in the midst of madness, in his 2005 film 'Joyeux Noël'. The event, covered up by the powers-that-be because of the threat it represented to the continued prosecution of the war, involved a Christmas truce and fraternisation between French, German and Scottish soldiers, heretofore slogging it out in the mud and slaughter of trench warfare. Carion creates a verisimilitude by casting each nationality from within the country they represent and has them speak in their own language, as the bloodshed stops for a day and the opposing soldiers get to see the reality of who it is they are killing.

In 1914, Carion shows a succession of images approximating Renoir-esque paintings of idyllic French life. He cuts to a series of young schoolboys from different countries reciting racist indoctrination, each condemning the other. A young man in Scotland rushes into the local church to tell his brother, "It's war", while in Berlin a German officer interrupts an opera to announce the Kaiser's declaration. A French officer vomits, before taking his men over the top in another futile charge against German machine guns in well dug in positions. The stalemate that exists between the lines leads to each side hearing the singing of Xmas carols on the night before the holiday, and one of the Germans takes a chance to walk out into no man's land to sing. The officers for each group convene on the spot an negotiate an informal truce for the evening, soon the soldiers are meeting each other and sharing drink and chocolate and showing photos of loved ones. The next day they again decide to continue the truce and to take the time to bury the dead, previously left to rot in the fields. The soldiers continue to liaise, playing football and enjoying the release from the grinding war.

The first Xmas of the war was an uncertain time, the propaganda in August was that it would all be over by then, but the optimism foundered against the reality of the trenches. The Germans came within an ace of conquering France, a decision to pursue a retreating French army instead of marching into Paris came back to haunt them when a Parisian home guard broke their lines and enabled a rear guard action to chase them to the countryside where they dug in. Small fields regularly took hundreds of thousands of shells before the inevitable and futile charge across no man's land by the infantry. Against this backdrop any respite from the industrial scale slaughter must have been welcome, and several positions in the frontline negotiated regional truces for Xmas. The counterpoint of the men finding other men just like them on the other side of the line is in poignant relief to the monsters outlined by the schoolboy's recitations.

After the fraternisation the soldiers aid each other in avoiding a bombardment from each other's artillery, swapping trenches as the shells rain down. The sad realisations that hostilities must inevitably re-commence reluctantly seeps in, "to die tomorrow is even more absurd than today", and the men endure official punishment when the scale of the 'treason' becomes apparent through letters home. The French Lieutenant is sent to Verdun, an almost certain death sentence in light of that battle, and the Scots regiment is disbanded.

Carion mixes in an appreciation of art and culture via the use of a renowned opera singer as a central character, Nikolous Sprink (Benno Fürmann), who volunteers as a private on the front line. The unifying theme of the universality of music enhances the human connection experienced by all levels of soldiery, from the milksop Bavarian Crown Prince to the lowest Scottish piper. After the superiors of both sides punish the soldiers through various means, though sentenced to the Russian Front, the Germans defiantly sing a Scottish folk song they learnt from the Scots during the cease-fire, after the Crown Prince had symbolically destroyed a soldier's harmonica.

The common religion the combatants share makes a mockery of the engraving on a German emblem, 'God is with us', as the Scots priest, Father Palmer (Gary Lewis) says mass in Latin, common for the time, and all respond in the same language. Later his Bishop, who informs him he's to be sent back to his parish, reprimands him and then presides over a service to new soldiers, encouraging them to seek out the evil "hun" in this holy "crusade", and to "kill them all". The Bishop uses the Bible verse that quotes Jesus as saying "I come not to bring peace, but a sword" and Palmer takes off his wooden cross and puts it down upon hearing his Bishop's bloodthirsty instructions. The irony that both sides worship the same God, told by their respective priests of the righteousness of their cause, is richly ironic.

Carion's film is a lovely reminder that what unites us as humans is infinitely greater than the things that divide us. If men can put aside their xenophobic conditioning and institutionalised brainwashing to find a moment of peace amidst the extreme brutality of WW1, then maybe there's hope for the human race after all?