Apple sliced four ways

By Michael Roberts

“It didn't get a fair shake because the Beatles weren't interested in it because they'd broken up. It just seemed like they didn't care anymore. That’s what happened in 1970.”

~ Michael Lindsay-Hogg (2024)

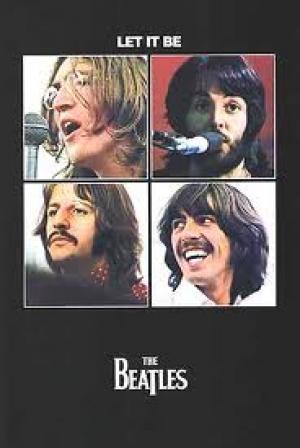

‘The flame that burns brightest, burns briefest’.... the Beatles career in a nutshell. In a barely credible total creative span of 12 years, the group went from pimply teenagers to fully-fledged artists and spent half of that span as the dominant musical force on the planet with a legacy that ripples into the 21st century. Originally intended as a TV concert promo, before plans collapsed, the Let It Be footage was compiled by director Michael Lindsay-Hogg for a feature documentary film release with UA, the company who handled all the other Beatle feature films. UA had signed a fortuitous 3 picture deal with Brian Epstein in late 1963 and had deemed the animated Yellow Submarine did not constitute fulfillment of the contract, so effectively their 4th film for UA, completed their 3-picture-deal... as usual in Beatleworld, nothing is what it seems.

Paul McCartney came up with the idea of filming the band rehearsing new material, for some short films to promote a planned concert. Venues were proposed and refused, such as London’s the Roundhouse, and even a large-scale concert in a Roman amphitheatre in Libya. The other Beatles reluctantly agreed, sensing that they needed to be occupied after a period of relative inactivity, and they had become increasingly rudderless after the death of their manager Brian Epstein in mid 1967. And so it came to be, that the single greatest musical act of all-time came to cobble together a plan on-the-fly - hoping as usual that things would turn out fine.

Michael Lindsay-Hogg, an American who had worked on TV show, Ready, Steady, Go, and who was purportedly the illegitimate son of Orson Welles, was selected to direct the project. Lindsay-Hogg had recently proved his rock and roll hip-ness credentials by filming the Rolling Stones concert 'event', Rock and Roll Circus, of which John Lennon was a key performer, and he set up his cameras in the cold and barn like sheds of Twickenham Studios and watched the band implode before his eyes. The band had not played live together for over two and a half years, preferring to sculpt their sound masterpieces in the studio, and the Twickenham sessions are rusty and loose, worse yet, the spirit is missing. Lennon, at his lazy and heroin hazed peak, is accompanied by his new muse, Yoko, who is a tolerated guest to say the least. The sessions fail to spark, and George leaves the band after an argument with Paul about a guitar line in I've Got a Feeling. Behind the scenes, the other three meet and placate George, who returns after his demands are met, namely; no more Twickenham, and no Roman concert – and (except for the non-event passive aggressive argument) none of this is shown in Let It Be.

The boys decamp to Apple Studios, recently acquired by their company on Savile Row, and are joined by an old Hamburg acquaintance in keyboardist Billy Preston, invited by George after seeing him play with Ray Charles. The sessions spark up, Preston serving the same function as Eric Clapton did when he recorded While My Guitar Gently Weeps with the band, both a creative catalyst and an emollient to get the lads to behave civilly to each other for a change. The material takes shape and soon a rough concert running order is possible, and the band decides to play the concert portion live on the roof of their studio in downtown London. The watering down of grandiose ideas, embraced in the heat of inspiration, to something far more prosaic was something of a Beatle trait at the time, and so the Roman amphitheatre became the rooftop of the building they were recording in. Six months later, the original idea for the name and cover of their last recorded album, Everest, was to shoot the Fab Four on Mount Everest, but Northern pragmatism took over and it took them half an hour to wander outside the EMI studio in St John's Wood to create an alternate iconic cover, and to then settle on the new name Abbey Road.

The final cut of the film, culled from dozens of hours of documentary footage is a fascinating document of a great partnership in the throes of disintegration. Lennon’s extended depression, which saw him mired in drugs and ennui, was ending via his lifeline with the woman who would ultimately prove to be his soul mate - he resembled a man coming out of a coma and he was soon to explode with an extraordinary period of productivity. McCartney stepped up to cover the vacuum left by Epstein’s death and Lennon's inactivity and got unfairly vilified by George and John for doing so, as both he and John had to accommodate a blossoming writing talent in Harrison and his competition for precious album space. The personal politics saw the fracturing of the once tight unit, but as always when they were fully focused on the music the results were first class, and any body of work that includes Don't Let Me Down, Let It Be, Two of Us, I've Got a Feeling and The Long and Winding Road has plenty to recommend it.

The music in Let It Be spoke to the growing dissatisfaction with elaborate and rococo sounds in early 1969. Rock had outgrown its 'garage' beginnings and was now the domain of extended virtuoso solos and grand orchestrations, and after Bob Dylan's retreat to Woodstock, and the resultant 'get back to basics' ethos that The Band's Music from Big Pink evinced, many musicians were yearning for an earlier era, and its simple joys. The founding fathers of 'rock and roll' had been heavily out of fashion for many years, but in the late '60s package tours of the likes of Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley suddenly brought a new reverence for what they represented. Lennon and Clapton would famously play a revival concert with many '50s icons in Canada the same year, recorded for posterity on Live Peace in Toronto. I have a pet theory that any analysis of the surviving vinyl copies regarding the needle playing on the A-side as opposed to the Yoko screeching B-side will find very little wear on the B.

The Beatles conducted the sessions under this Get Back paradigm, and McCartney came up with the signature tune, initially a parody of the Enoch Powell racist rants then current in the political sphere. ‘Don't dig no Pakistanis taking people jobs,’ was ironic and meant as an anti-racist statement and the song was meant to be the title track for the album, but fearing the misinterpretation of the message, he diluted it into a spirited ditty about a cross dresser from Tucson and extracted a career best solo out of Lennon into the bargain. Harrison produced the lovely 12 bar romp, For You Blue, again pulling a great slide performance out of John and a sweet tack piano part from Paul. Waltz time is well represented by George's, I Me Mine, of which the playback features John and Yoko doing their ballroom blitz, (John probably avoiding playing George’s difficult chords he complained about) and John's slower Dig a Pony, with its wailing ‘All I want is you’ refrain, superbly harmonised by John and Paul and rollicking riffing. McCartney’s soulful balladeer finds full expression in his The Long and Winding Road, and in the memorable title track. Lennon later belittled the title song, during the bitter break up period, claiming Paul was interested in a Bridge Over Troubled Water type hit song, intimating he had ripped off the Paul Simon masterpiece to some extent, but McCartney’s song was actually written well before Bridge, (and released after) but Lennon was never corrected by his timid or lazy interviewer. Paul’s song was in fact based on a dream he'd experienced, where his late mother, named Mary, appeared to him and calmed his fears during that stressful time.

What remains startling is the realisation that the period the film covers, from crappy Twickenham rehearsals to the wonderful rooftop concert, is only four weeks! The band managed to coalesce around unknown songs, knock them into recordable shape, and premiere them to a bemused London lunchtime crowd in the streets below. The final album emerged after the tapes were handed to legendary producer Phil Spector, and he polished up the multi tracks and presented the album in the shape the world knew it in 1970, after Abbey Road had been released in mid 1969. McCartney was always unhappy with some of the Spector wall-of-sound string section and choir overkill, and eventually he oversaw a stripped back release, Let It Be Naked, in 2003.

The film Let It Be is the strange, unloved bird in the Beatle canon, under-seen and virtually disowned by the protagonists until the Disney 2024 release. It never had a widespread DVD release, and the amount of material not seen was widely mooted would make a Director's cut to die for a no-brainer option. Michael Lindsay Hogg’s first cut was an hour longer and it’d be fascinating if that ever saw the light of day, given what we know was available to him after Peter Jackson’s Get Back. That said, Lindsay-Hogg made no concessions with what he delivered in a pre-social media world where information about bands was so much harder to find. He gives no context for what is happening, no explanatory voice over explaining who the characters are surrounding the Fab Four, like co-producer Glyn Johns or keyboard player Billy Preston or why they changed studios midstream.

It is, however, the ultimate fly-on-the-wall doco, albeit unintended, and it served as the model of many a 'rockumentary', from Spinal Tap to Metallica, as it shows the group in a warts and all light, battling with the inevitability of change. It’s sad to see the edges of disintegration, but all creative greats have their time, and without the right conditions for an artist to thrive, decline is inevitable. The break-up of the Beatles saw a creative resurgence in Lennon in particular, as he embraced the wider possibilities in being a non-Beatle and created his self-analytical masterpiece Plastic Ono Band a mere year later. Paul maintained the high standard he set for himself with Abbey Road and produced classics like Maybe I'm Amazed and My Love soon after, preferring the life of a gigging muso. George came into his own with the epic All Things Must Pass, and even dear old Ringo found his feet as an actor and as a solo performer. Let It Be may have chronicled the end of an era, and it’s only right that it gets a fair shake in 2024 in the wake of Jackson’s tsunami. The new shiny, cleaned up print will hopefully put the original ‘cardboard tombstone’ crits to bed once and for all and take its place in the canon as a worthy marker for the next to last phase of a band that took all before them.

Michael Lindsay Hogg’s film may have had a bumpy ride, but the music is still enough to get lost in, time and again, and that’s no small thing. He was given a brief that changed almost as soon as his cameras started rolling and kept shooting knowing he would have something remarkable at the end. Without a clear vision he pulled a rough concept together on the run and topped it off with the joyful rooftop gig, fittingly the last time the band played in public together. He kept it simple and unfussy, and seemed to be saying, ‘It’s The Beatles, isn’t that enough?’ Given their singular legacy and place in history, he should have known (for Beatle fans young and old) that was never going to be enough.

"Sometimes things go your way in life, and sometimes they don’t. But I got very lucky twice with this. I did it originally, and then I got beat, but then it comes out again. So that’s a good conclusion to that story. " ~ Michael Lindsay-Hogg (2024)