Mambo Italiano

By Michael Roberts

"Cinema is an old whore, like circus and variety, who knows how to give many kinds of pleasure. Besides, you can't teach old fleas new dogs." - Federico Fellini

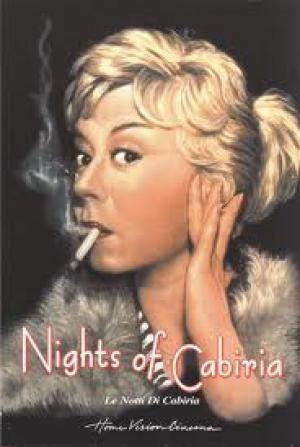

Fellini was still displaying some of his neo-realistic roots by this, his sixth film with his wife Giulietta Masina, (5 1/2 if you're counting a la Fellini) set as it was amongst the lower classes so beloved of the leftist champions of the genre. His international reputation, post their hit La Strada , was still high, and after this film, which contained less of a direct visual poetic overlay, he continued his progression towards a more personal and artistic style. The poetry of the piece is to be found in the humanity that Cabiria represents, and her response to life's travails and terrors, perfectly embodied in the expressive eyes and tender portrayal of Giulietta Masina. Masina carries the film on her tiny shoulders in one of the great screen female roles, which deservedly won her the Best Actress award at Cannes.

Cabiria is walking with her boyfriend Giorgio by the river, she thinks he's romantically out strolling with her as she swings her purse in delight. he grabs the purse, pushes her into the river and runs off. Welcome to Cabiria's world! Dragged out of the Tiber like a near dead cat, the feisty Cabiria throws off the effects of the near drowning to return to her small home only to find Giorgio has done a runner, she burns his photographs and his things, "dirty vitteloni" she spits, Fellini's in-joke regarding his own coined word to describe a blood sucking loafer in a previous film, I Vitelloni, and the cute topper being Giorgio was played by vitelloni Fausto from that film, Franco Fabrizi in an uncredited cameo. Fellow prostitute Wanda sees what has happened, "he pushed you in", but Cabiria doesn't believe it, "I gave him everything, I'm no fool". She returns to working the streets, and spends a chaste night with a movie star, giving her a glimpse into how the other half (more like 1%) live. Fellini also gives her a window into a bleaker potential future by including a scene with an old prostitute who's fallen on hard times to the extent she's living in a cave and depending on charity from strangers.

In a series of vignettes Fellini reveals Cabiria's character, optimistic and resilient, likely to lurch into an endearing mambo at a moments notice, and taking a backward step for no-one. Fellini has her realise the cost of her lifestyle, a world she has known for years, "I don't remember how I started, I was a child", by being emotionally overwhelmed at a religious festival, and vowing to turn her life around, before the unlikely finding of true love with an accountant bewitched by her performance under hypnosis on a theatre stage. Oscar (François Périer) sees "purity and innocence" in Cabiria, something she never thought she'd hear from a man, and eventually he charms her to the point she sells up everything to go off and marry him. Cabiria believes her hoped for 'miracle' has been granted, and she bids Wanda farewell and sets off to a bright future.

Fellini moves towards the 'magical realism' phase of his career with Nights of Cabiria, and the ritualistic and mystical elements that would become more overt make their appearances here, in the 'Carnival of the Madonna' sequence, and in the cheap magician with the Devil's ears. Fellini is always comfortable placing his camera in the middle of a bustling crowd, extracting every ounce of chaos and claustrophobia in the process. The humanity of the women, the ordinary lives lived in quiet desperation, "everyone has a secret agony", are contrasted against the dream life of the movie star, a world so foreign to Cabiria and her friends it might as well be on Mars.

The ornate escapism that the churches and it's icons represent, offer the fantasy of relief in the next world is not in this one, "Are you in God's grace, are you happy"? a Christian Brother asks Cabiria as she's struggling with her decision to marry Oscar. Later Cabiria wants to take confession with him, as she wants to 'cleanse' herself of her past, but underlining her limited understanding of Christian bureaucracy, as he's not a priest he can't hear it and absolve her. This may symbolise the impossibility of truly denying a past, it's presence always informing the present, and for Cabiria that includes her propensity to see things in a deluded romantic sense, as per Giorgio.

Ultimately Cabiria only has her own self determination to cling to, her independence defines her and her indomitable spirit marks her as a survivor on the tough streets at the poor end of town. She emerges from the woods, beaten but unbroken, a little red riding hood with a Mona Lisa smile and a mambo-ish spring in her step, her inner self intact. Fellini delivers his fable with a great feeling for the ordinary people, even if he did have Pier Paolo Pasolini render the dialogue into a Rome street argot and have him scout the locations for the 'lower depths' that give the film it's realistic feel, something Pasolini knew a thing or two about.

'Nights of Cabiria' set Fellini up to move into his richest period of artistry, sans Masina, where his neorealism finally made way for a mature and coherent vision of a world where reality, fantasy, culture and art all have equal weight as his characters explore the nature of their lives and try to find authenticity and meaning. Fellini soon came under the spell of Carl Jung and his interpretation of dreams, and every film after La Dolce Vita carries this new and profound influence. La Dolce Vita became a sensation and a byword for modernistic cool, a touchstone for the 'cinema du alienation' as was Antonioni's L'Avventura. Fellini's existentialist masterpiece of an artist in crisis, 8 1/2, followed and his immortal reputation as a cinema legend was assured.

* Nights of Cabiria was re-made in English as the musical Sweet Charity, directed in 1969 by Bob Fosse and starring Shirley Maclaine, (being Hollywood, unsurprisingly, the prostitute is now a dancer). That's showbiz.!