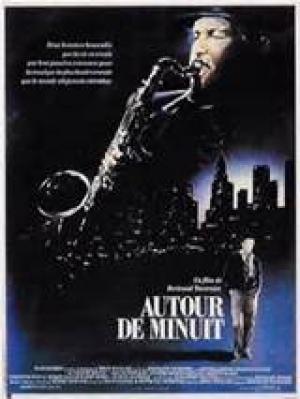

Paris blues

By Michael Roberts

"Jazz washes away the dust of every day life."

~ Art Blakey

Bertrand Tavernier’s awareness of the deep links between Jazz music and Paris is at the heart of his homage, one that showcases the singular talent of jazz original Dexter Gordon. Tavernier used the work of Francis Paudras and his memoir that featured Bud Powell as a starting point for his material, and also raided stories about Lester Young to fatten up this fine mood piece, with François Cluzet playing the Paudras character, the star struck fan that helps out his musical hero in the last phase of his life. The film is a series of encounters between the odd couple and relies heavily on superbly orchestrated live gig sequences that feature live performances from Gordon and a crack band led by maestro Herbie Hancock.

Dale Turner (Dexter Gordon) is living hand to mouth in New York and relying upon the kindness of friends and strangers when he gest an offer to play in Paris. The French revere American Jazz musicians and the music is not only popular, it’s lauded as an art form. Turner sets up in Paris but again struggles with his addictions and inability to conform to ‘normality, and only comes alive with a saxophone or glass of bourbon in his hands. Francis (François Cluzet) is an obsessive Jazz fan who invites Gordon into his life, befriending him as he enters the inevitable last phase of his career. Together with Francis’ young daughter Berangere (Gabrielle Haker), they form an unlikely friendship.

Turner, the weary troubadour seems at odds with the world, only able to connect during the short time on stage where every thing else vanishes and the perfect note is always a possibility at any given time. If being a great musician means being able to have a musical conversation with ones peers, then it’s possible that great musicians have nothing left over to enable the small talk and casual oiling of social intercourse that comes with the mundane interactions of everyday life. Francis, in his idealistic way, stays with Turner where many had left, and discovers that beyond the gruffness there is a man wanting connection, but unable to articulate it to any coherent degree. Like music, their relationship exists in the pauses and the silences, as much as in what is said, and in the joint interest they share in Berangere, the young girl who represents an unexpected hope for the all but burnt out musician.

Francis finds solace, comfort and inspiration in Turner’s expressive work, as he struggles himself to provide a life for his daughter, and is convinced that anyone who can create such sublime artistry must have some insight into the human condition. If music takes over where words stop, then Francis has to face the fact that not all of the factors that work to shape our philosophies can be expressed as dry, logical theorems. Music is poetry for the heart, it is Turner’s gift to humanity, and ultimately the irony that such a talented musician has had to suffer in order to reach that level of expression is one of the paradoxes of life.

Tavernier’s meditation is a sweet and poetic mood piece that affirms the value of art and of human connection. In the wake of WWII the French (more than most) were searching for new ways of finding meaning, and were consequently open to new ways of expression as Existentialist writers like Camus and Satre were gaining currency. The Nazi occupation had cut off the French from any allied cultural imports like film and music, so after the liberation they caught up with a vengeance, fuelled by US Armed Forces radio and a steady diet of a new and harder Jazz music called Be Bop. The French cineastes also noted the darker strain that had seeped into American film, dubbing the new direction Film Noir.

Be Bop greats like Charlie Parker and Miles Davis were drawn to Paris, stunned to find their acceptance as artists and, more importantly, as men to be devoid of the racism they experienced on a daily basis back in the states. A lucrative and established touring circuit in Europe grew up to support many American jazz acts, most of them African-American, and it was into this environment that Dexter Gordon plied his trade from 1959. Gordon played with Bud Powell, the hard living pianist who helped establish Be Bop’s credentials. Another key figure, one of Be Bop’s founding fathers, Thelonius Monk, befriended Powell, and Powell was the pianist on Monk’s composition, Round Midnight in 1944.

Dexter Gordon brings all the emotional baggage of his own struggle as a jobbing, hard scrabble Jazz musician to the role, which adds a verisimilitude that would be impossible to imagine otherwise. Gordon was, in effect, playing himself, and obviously he did it so well he even earned an Oscar nomination for best Actor. Gordon’s musicianship is a highlight, aided and abetted by a first rate line up of modern Jazz greats, led by Herbie Hancock in ensembles that includes John McLaughlin, Wayne Shorter, Ron Carter and Freddie Huppard. Tavernier films the gigs live, rather than having these stellar musicians mime to pre-recorded tracks, and the results are a joy to hear, vivid, exuberant and touching. Tavernier gets a lovely performance from a relatively young Cluzet, and nice cameos out of Martin Scorsese and Phillipe Noiret to round out a fine supporting cast, all in service of the tone and mood of his wonderful homage to Jazz.

Bertrand Tavernier remains one of the most significant French directors to emerge in the post Nouvelle Vague era, carrying on the torch of the leftist, vital cinema of Melville, with the humanist panache of Truffaut. Round Midnight is his homage to a life in art and to fatalism, a poetic tone poem to a musician “still playing those weird chords” and searching for the perfect note, the escape route from a life of self-destruction and excess. Tres bon!