Hitch's highland fling

By Michael Roberts

'Self-plagiarism IS style.' ~ Alfred Hitchcock

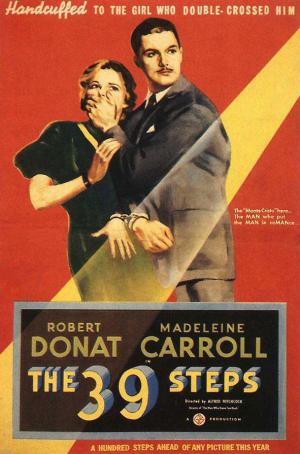

Hitchcock had been involved in making films for 17 years when he completed The 39 Steps - it coming in the middle of his golden era of British cinema and establishing him as an international success at last. In 1939 he gave up the UK after an offer from producer David O Selznick, then the hottest name in films, to ply his trade in Hollywood, where he would virtually remake this film over 20 years later in North by Northwest. The 39 Steps contains many of the Hitchcockian trademarks that would make his name a by-word whenever film director’s are discussed, and indeed may represent the pinnacle of his ‘wrong man’ motif, or at least the equal to any he would make in the future. The source novel from John Buchan, surprisingly the Governor General of Canada at the time the film was made, was a huge publishing hit in 1915, but Hitchcock makes several substantial changes, making the spy at the beginning a woman, crucially adding the character of Pamela (who is chained to the hero Richard Hannay for long periods of the action), excised a political assassination plot, even changing completely what the 39 Steps were. Surely his changing the nationality of Hannay from Scot to Canuck is a sly joke on Buchan as well as a way of avoiding Donat having to adopt a Scottish brogue?

Hannay (Robert Donat) walks into a music hall for some entertainment, on the bill is Mr Memory, who has instant recall of everything he’s ever read and answers the audience members questions. Hannay’s question establishes him as an outsider, a Canadian amidst the raucous working class at play, and when a fight breaks out and a gun shot causes a stampede, he stumbles outside thrown into the arms of Arabella Smith (Lucy Mannheim) who startlingly for the era invites herself home with him, ’it’s your funeral’ he deadpans. This is a classic use of sexual undercurrent in Hitchcock’s work, the girl is seemingly self-assured and the hero seems a little fey, but has not yet been ‘called to action’. Miss Smith, it soon transpired is in danger, she tells Hannay of her mercenary spy work and that she’s been followed to the flat by men intent on killing her. Hannay believes she has ‘persecution mania’ but feeds her and gives her a bed for the night, when she stumbles in to his room later with a knife in her back, clutching a map of Scotland, he changes his mind. The much discussed ‘McGuffin’, Hitch’s catch-all descriptor of the usually unimportant device to propel the action, is in this case a death scene reference by Arabella to ‘the thirty nine steps’, the hero needs to discover what it means in order to free himself from the mortal threat he now faces. Hannay eludes the would be killers, after another sexually charged cover story told to the milkman (nudge, nudge, wink, wink…) and takes the Flying Scotsman north, towards the village destination circled on the map.

On the train Hannay notices that he’s made the front page as the suspected murderer of Miss Smith, and when police sweep the train he bursts into the cabin of Pamela (Madeleine Carroll) kissing her, before explaining who he is. She gives him up to the police and Hannay jumps out of the train and sets out on foot across the Scottish moors. Hitchcock again undercuts the serious predicaments with sexual humour in the train scenes, where two salesman discuss and display ladies underwear! (Hitch, seriously, get some therapy! :), that Jesuit upbringing has a lot to answer for) He arrives at a crofter’s cottage and buys some refuge for the night, but when the police arrive is helped by the younger wife (Peggy Ashcroft) who responds to Hannay’s charm and decency. Now wearing the crofters coat Hannay finally finds the Professor that Smith had mentioned, but soon finds he’s a double agent and is shot and left for dead. Hitch cuts from Hannay being shot to black, then opens up on a scene where Hannay is explaining to local sheriff that a hymnbook in a chest pocket saved his life, the sheriff calls in the police, to arrest not to help Hannay. Hannay escapes to a political meeting in a hall and runs into Pamela again, this time he’s caught by the Professor’s henchmen posing as police, taking Pamela along on the pretence she is to give evidence against Hannay. Pamela is handcuffed to Hannay in the car, but when the opportunity presents Hannay makes a break for it, this time dragging Pamela along. They make it to a small hotel, posing as newlyweds and in a delicious scene she has to take off her wet stockings while Hannay’s hand has no choice but to caress her legs (stop giggling you boys down the back!). Pamela who hasn’t believed Hannay until now, overhears the henchman talking to the Professor on the phone and relates to Hannay the plan involving the London Palladium. They arrive at the theatre only to see Mr. Memory on stage, Hannay spies the Professor in a stall, and as the police close in on Hannay he shouts out to memory ‘What is the thirty-nine steps’? As if programmed by a hypnotist Mr. Memory starts to identify a secret spy ring only to be shot by the Professor who leaps Wilkes Booth like onto the stage and is captured.

One of the delights of this film is the rich vein of humour that runs through it, and for this Hitchcock always cast charming actors, both for heroes and villains. Robert Donat is a Hitch hero par-excellence, it’s a pity poor health prevented him from doing more work, but his legacy is primarily ensured by his sure handling of the Hannay role, it requires him to be decent, but also knowing and he manages the dichotomy brilliantly. The uber-blonde which would populate so many of Hitch’s films and surely fill many a thesis of Freudian analysis, is filled by Madeleine Carroll, and she provides a sexy and witty foil for Hannay, she went on to work with Hitchcock the following year in Secret Agent. Hitch keeps the verbal sparring and chemistry front and centre understanding that the audience was far more interested in the bedroom than in the ‘Who done it’? aspects of these stories. His economy of movement and light touches are evident all through the film, never more so than at the end where, for all their time reluctantly being chained together, the final image of the film is of Hanny’s and Pamela’s hands joining together voluntarily.

Hitch had a budget to pull out all the stops and the production is high value, he even has the police use a primitive helicopter in the chase across the heather! The film is crisply shot and tightly edited, his producers intent on an international success, not just a local one. They got that, and much more besides. Early, but essential Hitchcock, enough said.