Pinter lets them all talk...

By Michael Roberts

"As far as I'm concerned, 'The Caretaker' is funny up to a point. Beyond that, it ceases to be funny, and it was because of that point that I wrote it."

~ Harold Pinter

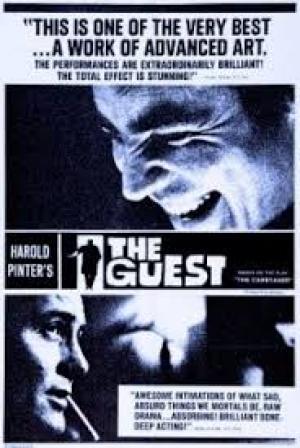

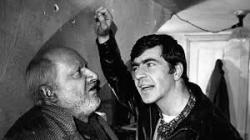

Harold Pinter almost single-handedly changed the landscape of British theatre in the late 1950’s and early 1960’s as his existentialist meditations on identity and pain took the so-called ‘Kitchen Sink’ realism of post WWII productions into a scarier and more elliptical territory. If his critical reputation was made with 1957’s The Birthday Party, his commercial reputation was made with his first hit play, The Caretaker in 1960, and Clive Donner committed a version to celluloid in 1963 with 2 of the original cast in Donald Pleasance and Alan Bates reprising their stage roles. They were joined in the 3-hander by Robert Shaw, who would become a Pinter specialist, and the piece was beautifully shot in black and white by cinematographer and future director Nicholas Roeg.

Aston (Robert Shaw) brings home an older man, Davis (Donald Pleasance) who is down on his luck. The two establish an awkward relationship, yet Davis takes up Aston’s offer of staying a few nights until he can go to Sidcup and get his ‘papers’. Aston leaves the next morning and Davis is then surprised and interrogated by Mick (Alan Bates), who is Aston’s younger brother. The brothers eventually make the older man separate offers to become the Caretaker of the old house, which is in need of repair and renovation.

"The only theatre I ever saw was Shakespeare." ~ Harold Pinter

In the aftermath of WWII, many playwrights, took to exploring a theatre of the absurd in order to process the calamity and cost of the fight against fascism. Pinter took to following Irishman Samuel Beckett’s lead and his seminal Waiting for Godot in 1953 and produced plays of oblique minimalism with a sideline in droll, English humour to undercut the misery and pain in the ordinary lives he essayed. In the late 1940’s, mainstream British theatre was either focused on a Shakespeare centric roster of classics or a reliance on the escapist Noel Coward-esque world of the impossibly chic and wealthy, before the 1950’s opened the door to working-class voices and stories. The era of ‘Kitchen Sink’ realism afforded an opportunity for embracing an outsider like Pinter, an arch observer of English life and mores, who remarkably was to move from being on the outer fringe of the theatre industry to becoming a central player in a few short years

In the years after WWII the notion of repair, or of reclaiming and reutilising ‘damaged’ goods were strong metaphors to bring into play in regard to the damages wrought on the human psyche by the wrenching conflict. The biggest sin in this society is to be useless, and Pinter sets up the notion of the middle class, represented by the property owning brothers, being estranged from the working class, as represented by the Caretaker. Central to the dialogue between the characters is the notion also of the impossibility of communication – this operates on a class as well as an individual level. “You don’t get my meaning” is a recurring line, and it resonates on an existential level, acting as much as a crie de couer as conversational rejoinder.

In any hierarchical society, i.e. one that values ‘place’ and heritage above ability, the idea that one knows one’s place is pivotal. This feeds into the fabric of that society and reveals itself in unpleasant ways, where one section looks down on another, reaffirming sometimes racist or bigoted beliefs. Davis, even though he’s on one of the lower rungs, looks down on the “blacks” as his inferiors, as for this type of society to function it requires scapegoats. All the protagonists are looking for a mystical fix to their problems - Davis thinks if he can just to get to Sidcup to get his “papers” everything will be alright, Aston wants to build his wall and finish his shed, and Mick airily dreams of renovating the house, “a table in... in afromosia teak veneer, sideboard with matte black drawers, armchairs in oatmeal tweed, a beech frame settee with a woven sea-grass seat... it wouldn't be a flat it'd be a palace.” All the characters speak of action, but none of them ever take it, doomed to scapegoating their lack of action on the oppression of ‘others’.

Clive Donner managed to use the central location of the film in a way that didn’t betray the theatrical origins of the piece, finding places for his camera that revealed every ounce of the actor’s intent. He was much aided by an unusually askew score, and all the appropriate for it, from BBC workshop stalwart Ron Grainger. The production of the film would not have happened but for the personal donations of several famous stars keen to promote the work, including Richard Burton, Elizabeth Taylor, Noël Coward and Peter Sellers.

The Caretaker is an understated masterpiece, superbly acted by all three men and stunningly crafted by Donner and Roeg, but all of that said, it’s a Pinter project. Pinter made his reputation with his downbeat, offbeat pieces and for all the play’s brutality and examination of banal, everyday human cruelties, its humour and wit shines through, giving if not hope for the human condition at least some balance, some light in the gloom. Essential viewing.