Lewton's law

By Michael Roberts

'Filmmaking is akin to writing on water' ~ Val Lewton

Hollywood in the ’30s and early ‘40s was a producer's industry thanks to the production line ethos of the major studios, eager to standardise production line output in order to maximise profitability a la Henry Ford.. In the days before the ‘director-as-auteur’ became a standard model of provenance in cinema the producer could rightly claim to be the guiding artistic hand on many projects, and none more so than Val Lewton. Lewton was a well educated Russian born aesthete, and after serving several years as apprentice to uber-producer David O Selznick he got the chance to head up a low budget unit for troubled RKO. The studio was in a major financial hole after bankrolling the artistic vision of Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane and Magnificent Ambersons, both now considered critical triumphs but failures by commercial Hollywood standards of the day. Lewton’s brief was a simple one, make films for less than $150,000 each and from a succession of pulp-ish titles provided by the studio, the first being Cat People in 1942, which made over $4 million and restored RKO’s fortunes, also freeing Lewton to pursue his artistic agenda unimpeded for several years, Seventh Victim was the fourth film in this cycle.

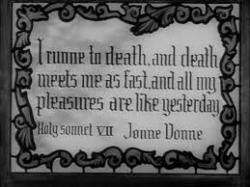

Working with very low budgets proved to be it’s own strength for Lewton and the various directors he collaborated with as the horror had to be suggested rather than seen. Put simply they wanted to make the kind of box-office hits Universal were having with titles like The Wolf Man, but couldn’t afford the makeup and effects for an actual monster. Lewton understood that psychological terror comes in the silence’s and imagining’s, not only in the visceral, and this combined with a decidedly existentialist philosophical core made Seventh Victim a remarkably chilling and effective slice of horror-noir. Lewton incorporates many existential tropes into his work, not least the angst and dread that hangs over his characters, and as an educated man would almost certainly have been acquainted with the works of Kierkegaard, his musing gaining prominence in the late ’30s and early ’40s via the prism of the French philosophers Camus and Sartre. Camus posited ‘there is but one philosophical question, suicide’ , the existentialists took it further, life is only worthwhile if suicide is a viable option. This acts as the creed of the central character in ‘Seventh Victim’, the seldom seen but unforgettable Jacqueline Gibson (Jean Brooks).

KIm Hunter, who would shortly star in the remarkable British film by Powell and Pressburger, A Matter Of Life and Death, makes her screen debut here as boarding school student Mary Gibson, Jacqueline’s younger sister who is troubled by the sudden lack of communication from her sister and goes to New York to find her. She discovers that the cosmetics business Jacqueline owned is in the hands of another woman, Mrs Redi, and that Jacqueline hasn’t been seen for months. Following several leads she finds a room her sister has rented above ’Dante’s’ (yes, Dante’s) restaurant and when she has it opened the only objects inside are a chair and a noose hanging from the ceiling. Mary soon encounters other interested parties in her sister’s disappearance, a psychiatrist, a poet and her lawyer husband amongst them. It soon transpires that the beautiful and mysterious Jacqueline is in the thrall of a cult of Satanists in Greenwich Village, and the quartet engage them in a struggle for her body and soul. The group of Devil worshippers eventually manage to bring Jacqueline to their meeting place, where she’s told to drink the poison they’ve prepared, and as she’s been suicidal before they imagine she will readily assent. She tells them her suicide will be at a time of her own choosing and refuses at first, then as she is about to crack after sustained pressure she’s prevented from drinking by Frances, a woman who worked with her and seems to be in love with her as well. The sect is dedicated to ‘non-violence’ in their charter and so let Jacqueline go, but shadow and torment her as she retreats to Dante’s. In a remarkable and poetic denouement she encounters Mimi, a terminally ill woman who lives on the same floor, a perverse mirror of herself, who declares she’s putting on a gown and going out for a night on the town to live one last time. ’I’m dying' she says and Jacqueline replies matter-of-factly ’I’ve always wanted to die’. A little later Mimi passes by Jacqueline’s room, her makeup on and dressed to the nines, she hears a dull thud from Jacqueline’s room but fails to register the significance.

To have a central character so obsessed with death was unusual to say the least in 1943, and Lewton and Co don’t let society off the hook so easily either. Institutions of law, medicine and the arts are all represented by the Doctor, Lawyer and Poet characters respectively and all are impotent in the face of Jacqueline’s emptiness of spirit, unable to help her invest meaning into her superficial existence. Lewton even underscores the superficial life she leads by having her own a cosmetics company in case we missed the point! Her lawyer husband admits defeat and falls in love with the younger and less challenging sister Mary, who ultimately is at least left with this love to help cover the loss of her sister. The Satanists continue on, unconvinced by the poet’s quoting of the Lord’s Prayer as evidence that good is better than evil. Lewton here is not interested in the issues of Theodicy as much as admitting that good and evil coexist in the world. The coven in a comfortable urban environment will feature again many years later in Polansky’s psych-terror masterpiece Rosemary’s Baby.

Visually the signature is pure noir, and given the darkness of the subject matter it would be appropriate to view them as such, the lighting and cinematography feel more like ‘A’ pictures than ‘B’ fillers, and it’s a credit to cameraman Nicholas Musuraca that so much was achieved for so little. There is a cleverly shot shower scene with Mary that uses shadow as effectively and imaginatively as Hitchcock would years later with Psycho. The cast is more than competent and possibly the fact that great range was not required from his actors enabled Lewton to use ‘types’ to great effect. Jean Brooks has to look downbeat and moody and not much else, and most others have to play to one characteristic more often than not, so blessedly these are not ‘actors’ films, and don’t suffer from Lewton’s lack of access to star power and range.

The sudden and downbeat ending owes something to the French Poetic Realists of the 1930s who incorporated a philosophy of fatalism into their work and it’s perhaps not surprising that Lewton would later work with Jean Renoir in his last Hollywood film, the noir Woman On The Beach. Mark Robson, who had edited several of the early Lewton horror films (having graduated from editing Welles' Kane and Ambersons) directed for Lewton on this one and would go on to have a long and respectable career, eventually making many A grade pictures, no doubt employing all the tricks he learnt from his mentor Val. Seventh Victim is an insightful and surprising film, beautifully staged and lovingly put together by craftsman who knew a thing or two about making movies.