The searcher

By Michael Roberts

"I felt pretty comfortable with Westerns, apart from the fact I couldn't ride."

~ Richard Widmark

John Sturges graduated from editing and art department work with RKO in the 1940’s to a directing contract with Columbia after the war. He’d served in the Air Force and learned from William Wyler during the conflict, working on the outstanding documentary Thunderbolt, with the acclaimed director. He made several Film Noir’s and also worked for MGM during the early 1950’s before finding his metier with action films and westerns, eventually rising to become a master of the form. During a period where westerns were becoming increasingly devalued by the ubiquity of their presence on television, several directors like Budd Boetticher and Anthony Mann were still making taught and stylish westerns, and Sturges joined their number with Escape from Fort Bravo in 1953 and with Backlash, an intense psychological western from 1956.

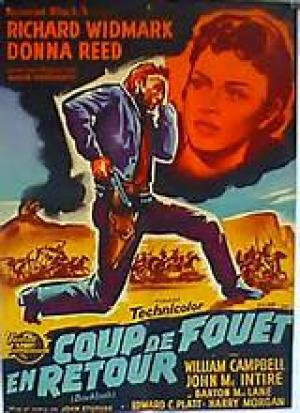

Jim Slater (Richard Widmark) is a man out to avenge the death of his father, a man he never knew, but who was reportedly killed in a deal over gold by a mysterious 6th partner. Jim meets Karyl (Donna Reed) at Gila Valley, the site of the murders, and it becomes clear they are both after the same end. They eventually form an uneasy alliance as they uncover clues to the identity of the killer, and of the unknown survivors. They track down an Army Sergeant (Barton Maclaine) and survive an Indian attack before the soldier gives up vital information. The trail leads them to Texas where they get caught in the middle of a range war, sparked by the arrival of the moneyed and brutal Bonniwell (John McIntyre) a man with a dark past who fancies himself as a land baron.

Backlash was the product of a time when the psychological western was reinvigorating the form, giving new depth to the classic mythology of the west. It made it possible for actors who were identified with the modern urban environment, like Widmark, and Robert Ryan et al, to work in the form and to be convincing in ways that were impossible for the generation before, where actors like James Cagney and Humphrey Bogart looked out of place in the saddle. Richard Widmark had made a career playing villains in urban, Noir thrillers, but his late career included many fine westerns, eventually with the master John Ford himself in Cheyenne Autumn and Two Rode Together. Chase’s script downplays the Freudian overtones of the narrative, and Widmark is archly cool against the overheated angst of William Campbell’s overwrought, hot-headed young gun-slinger.

Backlash has none of the cultural revisionism of the later Ford pieces, and the film focuses on the period immediately after the calamitous Civil War, where a collective will to ‘go west’ became a national distraction to the pain of the internal conflict. Unfortunately the indigenous people, the Native American Indians became the victims of a kind of west fever, where the lure of land and gold ran roughshod over matters of humanity and fairness. Backlash makes no effort to contextualise the plight of the Indians, and merely makes use of them in a particularly well shot action sequence where they lay siege to a trading post. The drama in the piece comes from the relationship of the two central characters, both damaged and driven and in need of redemption. Backlash plays as an intimate quest drama, a searcher looking for an answer, without the epic grandeur of Ford's masterpiece The Searchers, from the same year.

The attraction for modern audiences is the strength of the lead actors in roles that mostly avoid stock caricatures, beautifully played by Widmark and, more surprisingly, Donna Reed. Reed was known as the quintessential girl-next-door and had entrenched that image by starring in Capra’s perennial favourite It’s A Wonderful Life, and was recognised by her peers with a Best Supporting Actress Oscar for her role in From Here To Eternity. Reed plays a woman with edge and grit in Backlash, wielding a horsewhip and wearing black she gives as good as she gets and is not above triggering one man to into a gunfight against another if it suits her purpose. The ambiguity extends to Jim Slater, as when we first meet him he appears to be digging where the gold was said to have been buried, but when confronted he denies being interested in the gold. Widmark is tailor made to play the tenor of the psychology of mistrust and duplicity, having done so well in tense, Noir-esque thrillers like Kiss of Death and Night and the City, and his edgy presence was well suited to this kind of horse opera. John McIntire, a veteran of Winchester '73 also deserves a mention for his fine cameo as the father.

Sturges had enjoyed great success, and earned himself a Best Director nomination with the remarkable modern western Bad Day at Black Rock the year before, so his status within the industry was at a high point when he came to this otherwise routine western property. Backlash was written by Borden Chase, a writer who specialised in westerns and who had provided Anthony Mann with 3 of his James Stewart collaborations in Winchester ’73, Bend of the River and The Far Country, as well as writing the Howard Hawks classic Red River. Backlash has more in common with the Mann films, particularly the psychology of the protagonist, a driven character ably portrayed by Richard Widmark. The father/son contretemps at the centre of Backlash would be echoed a few years later in one of Mann’s best westerns, Man of The West with Gary Cooper.

Backlash is a beautifully photographed western, worthy of the late career, low key efforts of Raoul Walsh and Henry Hathaway, directors who had a lot in common with the journeyman Sturges. the feel is western Noir, and it might have been done in black and white 5 years earlier, but competing with 1950's television meant brilliant colour and widescreen, and this gives it a more natural tone. John Sturges’ place at the top of the commercial Hollywood tree would come a few years later, with his American remake of Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (the classic The Magnificent Seven) and with his fine WWII epic, The Great Escape and given his Hollywood pedigree it spoke of a hard working Joe, a survivor rising to the top. Sturges, Walsh and Hathaway would be the first to baulk at being described as ‘auteurs’, but the facts speak for themselves when they were able to create a body of work that transcends the production line Hollywood ethos.