'He wasn't there again today, I wish that man would go away'...

By Michael Roberts

"The photographer in Blow-Up, who is not a philosopher, wants to see things closer up. But it so happens that, by enlarging too far, the object itself decomposes and disappears. Hence there's a moment in which we grasp reality, but then the moment passes. This was in part the meaning of Blow-Up". ~ Michelangelo Antonioni

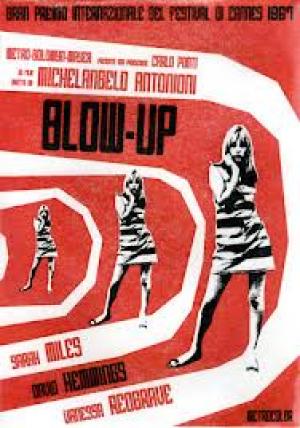

After a string of Italian triumphs and at the height of his acclaim as the most modernistic of cinema's visionary's in 1966, Antonioni decamped to Britain for his first English language film, the master of existential alienation meets Swinging London. Playwright Edward Bond translated the script, and David Hemmings, former boy soprano and protégé to Sir Benjamin Britten was cast as the photographer with no name, who nevertheless alludes to the then very famous David Bailey. Vanessa Redgrave in her first real year of doing film plays the main girl, a mysterious and troubled character, and the rest of the cast is mostly groovy-mod window dressing.

Antonioni examines little more than a day in the life of the photographer, as he exits a Doss house in London undercover and goes to his studio where a supermodel, the delectable but waif thin Veruschka awaits. In a photo session that approximates a sexual encounter he snaps off some rolls of film before sinking back exhausted and moving on to the next session. Bored and frustrated with the endless dolly bird merry-go round, he leaves the models and ends up in an Antique store, but then strolls into a nearby park with his camera. In the park he sees a couple, a middle aged respectable man and a younger woman (Redgrave) and he starts to take pictures before she sees him and challenges him. She tries to grab the camera but ends up at his studio trying to negotiate his giving up the roll of film. She disappears with the wrong roll and he develops what he shot, only to find more going on in the pictures than he thought.

The photographer is a man at a crossroads in his life, unable to find meaning in the superficial world that fashion photography offers, he is doing a series on the 'lower classes', hoping to sell a serious folio, realising no doubt that his reputation for 'hip' will see it end up as a bourgeois coffee table book. He aspires to purchase an Antiques shop, as if owning the past can give him an authentic life, he is, in Antonioni's world, a man in an existential crisis. His painter friend Bill (John Castle) of whom he is clearly envious, a 'proper' artist, implants a notion early by saying of an old painting he'd done, "they mean nothing at the time, but I find something to hang onto after, like a clue in a detective story". Bill has vaguely homosexual interest in the photographer, and he in turn is interested in Bill's wife Patricia (Sarah Miles) indicating a liberated sexual aesthetic to some extent and a reminder of the 1960's so-called 'permissive' society. Patricia confirms the link when she views the extreme blow-up of the dead body revealing photo later when she says, "It's like one of Bill's paintings".

The photographer's brief wakening from his numbed slumber is contextualised by Antonioni is his usual use of the symmetry available in architecture, the ordered and linear shapes found in the city, and in the softness of nature, even if it's the manicured and ordered variety found in a park, and he achieves a symbiosis of the two in the final setting, a tennis court in an area of the same park. His instinctively being drawn into the park and it's offer of respite from the hardness of his surrounds mirrors his inner dissatisfaction with his lot, and it's trigger in offering him a mystery to solve, leads him to obsessively invest in the 'trip' as a means to a hoped for redemption. He is only animated in a way that indicates he's at last emotionally engaged in his own life when he's describing to his agent Ron (Peter Bowles) how he's 'saved' someone from being murdered. This idea is frequently expressed in microcosm by Antonioni, as when the photographer appears listless and then suddenly springs into action, or collectively when the crowd at the Ricky Tick club appears bored to death watching the Yardbirds, they pounce on Jeff Beck's guitar neck when he throws it into the crowd. The stillness of the building lines are interrupted by the chaos and movement of students dressed like mimes careening around in a vehicle, and they later bring the same imposed but random chaos to the park at the denouement.

The photographer's narcissism leads him to inflate his own importance, from 'preventing' a murder, he obsessively digs deeper via his particular skill of blowing up his photographs, and sets out to solve one, a meaningful use at last for his work. Redgrave's duplicity reinforces that things are not always what they seem, and he eventually gets sidetracked by his own egoism, bedding a couple of ambitious models, while the whole possibility of doing something 'substantial' unravels. After a dope infused party night, he finds Ron who asks, "What did you see in that park"? to which the resigned photographer answers, 'Nothing'. He returns to the park the next morning and is confronted by the student mimes 'playing' tennis, in a beautiful visual allusion to people seeing 'nothing', the students all follow a ball that isn't there, only to have it hit out of the enclosure and onto the grass where the photographer conforms to the consensus view, picks it up and throw it back.

Blow-Up was the first Antonioni film to have a male lead, and in some ways the fact the character makes his living through the lens allowed Antonioni to comment on his own relationship to the art of the observer. Paradoxically the lens acts as a barrier for connectedness or involvement, and yet also offers a window for emotional investment, and typically Antonioni makes no attempt to offer a solution. It is what it is, an existentialist has to find his own meaning.

Herbie Hancock provided the music, in lieu of a score as it's situational but energetic and effective, with the Yardbirds including both Jimmy Page and Beck provide a scene stealing number. Apparently Antonioni wanted The Who for their instrument smashing act but couldn't get them, and so Beck offered his decidedly half-hearted variation. Antonioni signed a deal for 3 English language features, and the last two were equally stunning in their own ways, Zabriskie Point and The Passenger, but with Blow-Up he captured something both of its time and timeless, his meditative European sensibilities fitting nicely into the swinging London tempo. Groovy baby.