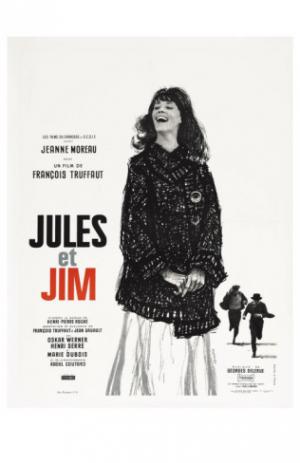

Jules et Jim et Jeanne

By Michael Roberts

'When humour can be made to alternate with melancholy, one has a success, but when the same things are funny and melancholic at the same time, it's just wonderful.'

~ François Truffaut

François Truffaut's third feature saw him to return to a more personally meaningful project, one he'd harboured ambitions for a few years to film, Henri-Pierre Roche's then neglected book about his own youthful experiences and published in 1952, Jules et Jim. Truffaut had tried to avoid being predictable after his succès d'estime with his magnificent debut feature, The 400 Blows, by making a 'gangster' film completely different in tone, but audiences rejected his quirky and offbeat sophomore effort and he fell back on something he was passionate about, the love triangle of the Great War era lovers. Truffaut feared his career may vanish as quickly as it started if his third film flopped (pity he didn't live long enough to see M. Night Shyamalan put that theory to rest!) so he had a lot riding on its success. Louis Malle had introduced him to the gorgeous Jeanne Moreau prior to his starting 400 Blows, and he cast her in the crucial role of Catherine as he'd long promised, collaborating intimately on creating a startling and memorable portrait of this singular woman. Catherine is the third name missing from the title, telling in its absence but the ineffable link between the two men. Henri Serre plays the Frenchman Jim, and for the German Jules, Truffaut cast an actor he had admired in Max Ophuls' film Lola Montes, Oskar Werner, who starred again for Truffaut in his only English language feature a few years later, Fahrenheit 451.

It's 1912 and Jules and Jim are passing their time by knocking about the streets of Paris and doing what young men have done since time immemorial, chase girls. Truffaut opens with a swirl of carnival type music from the pen on the immortal Georges Delerue as the lads play dominoes, smoke, eat and flirt. The two are close friends and their personalities merge to the extent that even their string of girlfriends confuse one for the other, they are effectively two sides of the same coin. An artist friend shows them some pictures of native art and they both become intrigued by the smile on one of the statues of a woman, and when they find a girl who resembles it perfectly they are both instantly besotted. The girl is Catherine, and she is unlike any of the others, a free spirit, smart and literate and more than a match for the two boys at every level. The trio do everything together and Jules soon warns Jim off Catherine 'not this one Jim', and during a holiday away Jules asks Jim if he should marry Catherine, Jim advises against it. Catherine tells Jim that she never used to smile, an ironic comment on the perpetually smiling statue, but that since she's met the two men she's been happy. The three are walking by a river bank discussing infidelity, the men assert 'a woman's fidelity is more important than a man's' and at that point Catherine jumps into the river in protest. At that instant Jim falls in love with Catherine, but she marries Jules. War intervenes, both men join their respective armies and are petrified they might kill each other, but they survive and Catherine lives with Jules in Germany and gives birth to a daughter. Jim visits and the three set up in a secluded chalet, and try to navigate the treacherous shoals of a labyrinthine and complicated set of relationships.

Catherine is the queen bee, the men the drones and like many of Truffaut's films this centres around the idea of the power women have over men, possibly his attraction to that trope is a hangover from heavily Catholic France where the Church has a kind of misogyny etched into its DNA such is its fear of what women represent? Truffaut channels it into an examination of the differences between the sexes, and Catherine represents a particular challenge for a conservative society as her sexual aggression and freedom crosses into typically and traditionally male areas of behaviour. Catherine's is a selfish and indulged existence, lived on her terms and not without consequences, she has a 'lightning curiosity' and an ability to manipulate people to her ends, ultimately she dreams of a relationship where two meld into one, when issues drive her apart from Jules she tells Jim they are now 'face to face, instead of merged as one', again an irony coming from one who is the 'statue to life' personification of a 'face'. When she is later estranged from Jim he observes that 'true love is controlling that adventurous impulse (lightning curiosity) for the sake of the other'. Catherine is unable to sublimate her needs to those of her partners and if true love demands compromise she's fated to be denied it. Catherine had to make to conformity is summed up by Jules at the end when her ashes could not be scattered to the wind as it was 'against regulation', death makes conformers of us all.

The film struck a huge chord with early '60s audiences all over the world, the portrait of a free loving trio expressing themselves in scant regard to convention resonated with a global western youth culture on the verge of the 'counter cultural' revolution. The Nouvelle Vague ethos of 'anything is possible' melds seamlessly with the philosophical core of Jules et Jim, even if there are to be consequences for such unconventional choices. "The future's bright for those who question" says Catherine. The film is a masterpiece of romantic melancholy, paced like a long and reflective piece of music with crescendo and diminuendo, soaring and graceful, and brilliantly realised by the three central performances. Moreau was never more effective, her trance like gaze lovingly photographed by a director in love with her, and the two men are superb. Astonishingly Serre never carved a career of any note in film after this! what happened? and Werner made some odd choices and could be wooden and mannered in the wrong part, but here he is pitch perfect and endearing. Jules et Jim is an ode to friendship, a hymn to love, immortal and indelible it speaks to the unutterable dimension of feeling more beautifully that any film dare to hope to.

Truffaut had a beautiful postscript with a letter from the real Catherine, then the only survivor of the original trio, who rushed to the cinema to see it upon its release, anxious to see her beloved Henri-Pierre's book transferred to the screen. Here's what she wrote;

“I am, at 75, what is left of Kathe, the awesome heroine of Pierre Roché’s novel Jules and Jim. You can imagine the curiosity with which I waited to see your film on the screen. On January 24, I ran to the movie theatre. Sitting in that dark auditorium, in the dread of veiled resemblances and more or less irritating parallels, I was soon swept along, gripped by the magical power (yours and Jeanne Moreau’s) with which you revived what had been lived through blindly. The fact that Pierre Roché was able to tell the story of the three of us and kept it very close to the actual events has nothing miraculous about it. But what disposition in you, what affinity, could enlighten you to the point of making the essence of our intimate emotions perceptible? As far as this goes, I’m your authentic judge, since the other two witnesses, Pierre and Franz, are no longer here to express their ‘yes’ to you. Affectionately yours, dear Monsieur Truffaut.”

- signed Helen Hessel

'Just wonderful,' indeed.