The war within

By Michael Roberts

'The real artists tells about himself entirely, with a perfect sincerity - but without knowing it. In spite of himself, he's conveying a message. If he starts his work explaining to himself, "I'm going to deliver a great message" - there's a very good chance he will not deliver anything at all.' ~ Jean Renoir

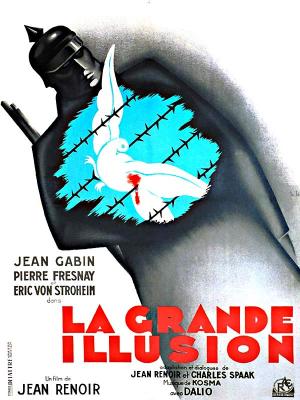

Doyen of the poetic realism movement Jean Renoir once wrote ’It’s not by being realistic that one has the best chance at capturing reality’, ergo La Grande Illusion is not a very ‘realistic’ war film at all. It shows no battles, no fighting, no drills, no explosions or bodies being blown to bits. Its focus is on the internal and external struggles within man, almost all of the action takes place in a prisoner of war environment, and avoids POW cliches of sadistic guards and plucky prisoners et al. By delineating a nuanced moral universe Renoir was able to make one of the greatest indictments of war ever filmed, and of the artificial barriers it creates to prevent true communality of spirit, one that is embracing of difference and not cowed into xenophobic myopia. Post WW2, French film greats Rene Clement and Alain Renais were also to use the same oblique method to illuminate the horrors of war with Jeux Interdits and Hiroshima Mon Amour respectively.

While constructing a personal humanist masterpiece that has at its core an understanding that the things that unite us as humans are greater than the things that divide us, the film cannot be viewed as other than a political statement. The film was produced on the tail end of a leftist French government and movement known as the Front Populaire, fighting the tide of right wing dominance in Europe, particularly in Spain, Italy and Germany, all the while knowing another war was all but certain. Renoir has as a central protagonist a Jewish character, Rosenthal (Marcel Dalio), who is pointedly generous, deflating the typical cultural/racial stereotypes that right wing groups of the period after the war shamelessly exploited, paving the way for Nazism. Renoir also has Marechal (Jean Gabin) drop an aside about the ‘Russian steamroller’, creating wry amusement amongst the soldiers. This referred to the alliance France had signed with Russia that should have ensured WW1 never happened, that the threat of the Russian steamroller would keep the Kaiser in check. Of course it was a myth or worse, a lie, as the disastrous early months of fighting for Russia proved, her army was shambolic, ill-equipped and at the mercy of an incompetent Tsar and administration as much as German bullets.

Renoir, who served in the Great War as an infantryman at first, and then later joined a flying squadron, made the film as a tribute to a friend of his who was caught and escaped the Germans 7 times.The film opens with a scene in the recreational hall, Marechal listening to a jaunty song and being ribbed about women by the other flyers, establishing him as a romanticist. His senior officer De Boeldieu (Pierre Fresnay) interrupts a potential tryst to enlist him in a reconnaissance mission to investigate an area over enemy lines. We see neither the plane, nor them being shot down, merely cutting to the German aristocratic officer Von Rauffenstein (Erich Von Stroheim) arranging to have the flyers dine with them in the German officers quarters, but only if they are officers. Renoir sets up the importance of class, even above nationality, as the aristocrats find they have more in common with their enemies than with their men. Formal codes, issues of honour and gentlemanly behaviour are tacitly understood.

The French are delivered to their prison and settle in to life in the camp. The lower classes deal with incarceration with humour and communality, the officers believe escape is a matter of honour. Levity is introduced via the prisoners putting on some entertainment, the lack of women creating both pathos and comedy when a young man dresses as a woman for the show, inadvertently attracting the gazes of the other men. Renoir uses news of a French town being re-taken by the French, then by the Germans then the French again (‘there can’t be much left of it’) as a device for Marechal to lead the men in a defiant singing of the national anthem (shades of Casablanca!) Marechal spends some time in solitary and suffers from being alone, Renoir knows that a man is a communal animal and to survive this extreme situation empathy and help is required, indeed he is given succour by an old German guard who passes him a harmonica to break the monotony. The French are re-located on the eve of an escape attempt, and find themselves at camp Winterborn, now being run by Von Rauffenstein.

War has been unkind to Von Rauffenstein and with his accumulated injuries he’s been invalided out of active service and reduced to the equivalent of a jailer or policeman, no honour in that for him. De Boeldieu renews his acquaintance with the German, and they discuss all manner of things, including a riff on how all upper class diseases will one day filter down to the lower classes and that war is an accelerator for this, "war makes all germs equal." Von Rauffenstein regrets the imminent passing of the system that has accorded them rank and privilege, De Boeldieu is more accepting of an egalitarian future, ironic given that some of the French foot soldiers had voiced mis-trust of his class behind his back. The German has difficulty in accepting the Frenchman’s acceptance of the Jew Rosenthal as an officer, surely an indicator of the decay of the aristocracy and “a charming legacy of the French revolution”. Von Rauffenstein knows his friend must attempt to escape, and ironically he is the one who ends up shooting him, respecting the fact that he’s sacrificed himself to allow the Jew and Marechal to successfully flee. He stays by his side as De Boeldieu dies with honour, ‘not a bad way out for us’, and Von Rauffenstein knows he is left with a future devoid of meaning, where existence is futile.

Marechal and Rosenthal make the long hike through the countryside heading for Switzerland, supporting and arguing, cajoling and falling out, finally exhausted they hole up in a remote farm house. At this point Renoir introduces Elsa (Dita Parlo) the only woman in the film, a German widow who helps them evade capture and in the process falls in love with Marechal, and he with her. Elsa has paid a massive price for her countries wars, not only her husband but mentioning a series of ‘great victories’ she points to a photograph of her three brothers that were killed in them. Language and nationality vanishes as love finds a way and human need trumps imperialism. The Frenchman finally escape over a non existent border ‘there are no borders in nature’. Jean Gabin delivers a riveting performance and is the beating heart of the film, achieved during a 5-year golden run of roles almost unmatched in all of cinema.

Renoir had a curiously old fashioned view of the Great War, common enough for the upper class of the time (and remember he was a veteran of that conflict), one that viewed the conflict as a ’gentleman’s’ war. This may be due to the fact that he was able to escape the horror of trenches and find some small degree of solace in the air. At its heart La Grande Illusion has hope for mankind. In all the mad, imperialist ugliness of that conflict there are the small moments that sustain us, the miracles of connection and empathy that rise above petty nationalism. Borders shift, governments change, class structures crumble, but human feelings are eternal and only by connecting ourselves and not shutting our hearts off can we survive and prosper. A timeless and masterful ode to humanity, the film was ironically mis-read and unappreciated upon release, a siren warning for the impending world war couched in the lessons of the first was too much for the national mood of France in 1937. Renoir was to move on to the glories of La Bête humaine and La règle du jeu the next few years before Europe again exploded and exiled him in the wave of emigres and refugees to Hollywood, who would have an equally problematic relationship with his singular talent. Renoir was an artist, as great as his father in many ways, his canvas the shimmering silver screen and his brushes the words and images with which to construct his poetic and revealing portraits like this one. Merci.