Poetic realism meets historical costume drama

By Michael Roberts

"I don't know what they'll say when I die. I don't give a damn. They'll probably cry." ~ Marcel Carné

Cry or not, they'd definitely be mentioning his undoubted masterpiece, Les Enfants Du Paradis , this lyrical and assured treasure remains the high point of Director Marcel Carné and writer Jacques Prevert’s collaborations and the culmination of the Poetic Realism cycle to which their names remain indelibly attached. The brilliant multi-leveled writing is matched at every point by performances and visuals that achieve a dream like symbiosis with the poetry of Prevert, and is imbued with the philosophical fatalism that defines the best of the Poetic Realist genre. The project had its genesis in an idea from actor Jean-Louis Barrault who suggested to Marcel Carné his next film be about 2 famous actors on the Boulevard Du Crime during the 1830s in Paris, Baptiste and Lemaitre, but Prevert was initially cool on the idea as he wanted to write a story based on an equally notorious criminal from that era, Larcenaire. Eventually they agreed on a story that included all 3 men and tied them together with their mutual love for the beautiful and remote Garance, played in one of the immortal performances by French icon Arletty. Production commenced under the restrictions imposed not only by the Vichy regime but also the privations of war-time France, where the materials and film stock needed for such an epic were in short supply.

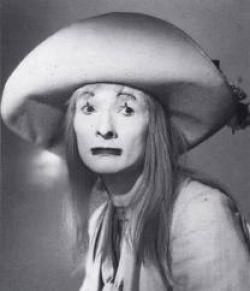

Divided into two roughly 90 minute sections, a requirement from the Nazi overlords, the story starts out by establishing Garance as the embodiment of beauty, but she is reduced to showing her assets in a cheap showroom on the Boulevard Du Crime, a cacophonous avenue crowded with assorted spruikers, criminals, fops, and fun-seeking Parisiens. Ambitious and self-centred actor (are there any others?) Lemaitre (Pierre Brasseur) spies her in the crowd and effusively attempts to win her over with words of love but Garance is immune to his charms and wise to every male ruse. Larcenaire (Marcel Herrand) is first seen as a scribe, writing love letters for the illiterate as a front to his business as a fence, and immediately Prevert is undermining the actor’s use of words. Garnace pays him a visit as he amuses her and he is fascinated by a woman who is in her own way as pragmatic as he is. Larcenaire has an ambition ‘to love no-one and be loved by none’, and foreshadows his own fate by telling her of his father’s warning of a future appointment with Mme Guillotine, one he fully expects to keep. Garance and Larcenaire stroll the Boulevard and stop at the Funambles, the mime show, where we meet Baptiste (Jean-Louis Barrault) who gets Garance out of trouble with the law over a stolen watch.

Lemaitre hustles a job as a comic lion at the Funambles, a friendship strikes up with Baptiste and soon they are sharing the same lodgings. Baptiste goes out nightly in search of the beauty he was smitten by and a blind man inadvertently leads him to her. Love is blind but also dangerous as Larcenaire and his thugs surround Garance in a low-rent bar. Baptiste wins the day with charm and verve and takes a homeless Garance back to his building where he organises a room for her. Baptiste declares his pure and idealised love for Garance and she offers her bed with a neutral ‘love is so simple’, he refuses until she returns his type of love in kind. Lemaitre hears her singing from another room and he spends the night with her. Baptiste writes a show for the Funambles with Garance cast as a beautiful statue, a love goddess whose stoney facade is silently mocking the kind of love the now forlorn and ‘lost’ Baptiste aches for. Count de Montray (Louis Salou) comes to see her every night and falls in love with Garance, wooing her with offers of support and shelter. Larcenaire implicates Garance in a murder attempt and when taken into custody she takes the Count up on his offer and disappears for several years.

In the intervening years Lemaitre and Baptiste have become big stars in their fields, Baptiste as the greatest mime of his age, and Lemaitre as a ‘matinee idol’ type, albeit one who still harbours ambitions of playing one of the great Shakespearean tragic roles, Othello. Larcenaire strikes up a friendship with Lemaitre under the pretext of being a writer, and comes in handy as a second in duel where Lemaitre is injured, ironically opposed to one of his show’s writers! An injured Lemaitre has time off and goes to see the sell-out show at the Funambles. The only spare seat that can be found is with a veil-faced rich society woman who comes every night and sits alone in a box, it is of course Garance who has at last realised it’s Baptiste she loves in the same way he loved her. An arrangement for Garance and Baptiste to meet is thwarted by Nathalie, Baptiste’s wife, who sends their young son to the box to show the life Baptiste now has. Lemaitre finally plays Othello and Garance and the Count attend, and a jealous de Montray assumes that the actor is the love of her life. Baptiste also attends the performance and finally meets Garance after the show, but the lover’s assignation is betrayed to the Count by Larcenaire whom the Count despises and insults by having him ejected from the theatre. Baptiste and Garance go back to the lodging room and Baptiste realises that ‘love can be so simple’, until complications arrive in the form of his wife next morning to plead her case. Garance leaves, knowing that the kind of love she shares with Baptiste is an unrealistic and ideal one, Baptiste runs after her, shockingly running past his young son in the doorway as he gets lost among the massive carnival crowd outside. Garance rides away in a grand coach, not knowing her Count is now dead at Larcenaire’s murderous hand, as Baptiste dissolves into a crowd of Pierrot’s and clowns, the ‘children of the gods’ dressed as actors.

Jean-Luc Godard said that ‘cinema spoke to the masses, and the masses love myth’, and just as he saw the roots of myth-communication in cinema came from theatre so it is that Carne explores the connection of the myth of ‘ideal’ love in the world of the arts and the actor, where the masses as represented by the ‘children of the gods’, are part of the narrative. Garance regrets losing the easy laughter of the ‘children’ in the cheap seats, an echo of the only truly happy time in her life, her childhood before her mother’s death, as in her adult life she is neither happy nor unhappy and so lives in a state of perpetual suspension. The tension in the piece is in the struggle between the dream world of ‘ideal’ love and the rough world of the actual experience of love, the dreamer versus the pragmatist. Baptiste is a dreamer who yields to the pragmatic in settling with a lovely wife and child, while Garance is a pragmatist who finally embraced the dream love she thought impossible, only to find it unsustainable. Lemaitre, the ultimate self-serving pragmatist, mocks the Count’s idea of love equating to possession, his impossible fantasy of owning the beautiful statue, a farcical and fleshless love that leaves real emotion unused, ‘the dead matter of love rotting in the brain of the unloved’ would be the fate of those who follow his path. Lemaitre finally realises what it will take to play Othello convincingly by being jealous of the depth of emotion Baptiste stirred up in Garance, his cynicism dented and his personal philosophy revealed as shallow and vain. Only Larcenaire remains true to his nature, ‘a thief by need, a murderer by calling’, content to keep his date with Mme Guillotine.

Prevert and Carné make great play with many actor in-jokes, ‘no wonder they only bury them at night’ exclaims Larcenaire, but at the centre of the film is the question ‘who is an actor’? Shakespeare wrote ‘All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players, they have their exits and their entrances’, Larcenaire also says ’actors are not people, they are everyman, and no man’, so Prevert is allowing the audience to project on to the actor’s what they need to see, just as the men each see in Garance what they need to see. At times it’s impossible to distinguish ‘real’ from ‘fake’ on stage, as during the brawl at the Funambles the ‘children’ think they are witnessing a performance fight, but it’s for real. Lemaitre deconstructs his cheap play by breaking the 4th wall and blurring the lines between character and actor, the audience not sure what is ‘written’ and what is not. All the while Carné is theatrically presenting a cinematic approximation of theatre life, so nothing is real. Except love.

Les Enfants Du Paradis remains an immortal ode to the power and purity of an ideal romantic love, however illusory or impossible it may be to obtain, to ache for it, to strive for it is a worthy pursuit in the eternal human dance of the search for meaning.