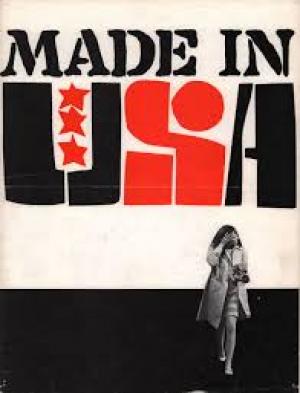

Godard's Dear John letter to America

By Michael J. Roberts

'The cinema is not a craft. It is an art. It does not mean teamwork. One is always alone on the set as before the blank page. And to be alone... means to ask questions. And to make films means to answer them.' ~ Jean-Luc Godard

Jean-Luc Godard came into 1967 at something of a personal crossroads but simultaneously focusing on the roiling student unrest and wider political scene as the counterculture generation started to flex its numerical muscle. After six full-length features with his wife Anna Karina, they bade each other adieu with this film, which curiously Godard shot concurrently with Two or Three Things I Know About Her, starring Marina Vlady, an actress he proposed marriage to, but who turned him down. In Godardian fashion he shot with his ex-wife in the afternoon and with his new lover in the morning, using the same crew and riffing like a jazz musician as he fashioned his words and frames to take his quixotic fancy. Made in USA was released first and Two or Three Things a few months later.

Paula Nelson (Anna Karina) is a journalist who returns to Atlantic City to meet her old lover Richard P, but upon her return she hears he has been killed. She is tailed by two heavies named Donald Siegal (László Szabó) and Richard Widmark (Jean-Pierre Léaud) and is seemingly swept up in a political intrigue as she tries to uncover the events behind his death.

Narrative, as it is understood in a traditional context, is disregarded by Godard as he searches for a cinema of feeling, more attuned to the senses of sight and sound than to logic. He says as much at the start when he dedicates the film to two of his cinema heroes in Samuel Fuller and Nicholas Ray – “Dedicated to Nick and Samuel, who raised me to respect image and sound.” Godard dismantles any expectation that either image or sound will conform to what mid-sixties audiences might reasonably expect, even if they come to the piece knowing his track record. The image he fills with pop culture references (especially his pet American cinema fetishes) as he invokes the classic detective genre of Hawks’ The Big Sleep, albeit through a quasi-Pop Art lens. The sound he fills with a potpourri of grabbed noises, high culture, traffic ambience, jet aircraft or cartoon adjacent comedic bits, deconstructing the discipline of film soundtracks as he goes - he even includes a cameo of the gorgeous Marianne Faithful singing an acapella version of her hit As Tears Go By.

For all of Godard’s multiple personal indulgences, the film is as much a love letter to Anna Karina’s face as to anything else. Godard was not the first director to fall in love with his leading lady, but his cinematic partnership with Karina was as devoted and committed as any, from Von Sternberg and Marlene Dietrich to his contemporaries Fellini and Giulietta Masina or Antonioni and Monica Vitti. The screen time he devotes to her is a tribute to their history, to her beauty and presence but also to her ability as an actress as she carries the film virtually on her own from start to finish, interacting with an array of ‘bit’ characters that are in no danger of staying with her long enough to develop into figures we care about. Maybe deliberately Godard only wants us to care for Anna.

Made in USA is deliberately allusive and elusive, it's Jean-Luc Godard is riffing on consumerism, American cultural imperialism, French politics, the Vietnam war, colonialism and drenching the screen in red, white and blue, the colours of the American flag, but also of the French tricolour. The America he fell in love with as a young filmophile had morphed into superpower behemoth conquering the world with rock and roll, Coca Cola and nuclear bluff. The Cuban Missile Crisis had brought the world to the brink of destruction and the doctrine of mutually assured destruction was fresh in the minds of the counterculture busy rejecting the mores of their parents and grandparents. Godard was politicised heavily by the Algerian War and as he moved progressively left, he embraced a radical and Maoist philosophy that would inform his persona for the next decade and make it unthinkable for him to make films like he had done before.

Godard splashes colour through Made in USA in a playful way, homage no doubt to Frank Tashlin as he satirises Hollywood violence and American aggression at the same time, rendering it as obviously fake and cartoonish here, or 'Walt Disney... with blood.' At the same time, he’ll fill the sound with quotes from poets or highbrow writers, contrasting the serious with the banal or ridiculous, as in the tape voice over that Godard himself voices – that of a political exile ranting into the ether. If American cinema attracted him as a younger man, he now recoils from the turbo-charged all conquering machine it’s become, railing against Madison Avenue and the military/industrial complex in equal measure, and concerned also for France not to be subsumed in a blitz of American cultural colonialism. 'I think advertising is a form of fascism,’ Paula says, distilling Godard’s fears in a single, pithy line, made all the more ironic by the fact that Karina worked as a model first and helped to sell Palmolive soap, Pepsodent and Coca Cola.

Made in USA is Godard’s howl at life, an existential rant that echoes the old blues question, ‘how can a man face such times and live?’ Godard flings all his might at the problem - visual, linguistic, sonic, conceptual and creates an impressionistic rendering of the madness of modern life, a fractured valentine to cinema’s part in his search for meaning and a frustrating Rorschach test for everyone else. It is also his 'Dear John' letter to America in many ways, acknowledgment that the things that made him and his generation fall in love with the idea or dream of America were overturned by the wanton capitalism of greed and of economic imperialism.

Made in USA was a continuation of the anarchy of Pierrot Le Fou and an anticipation of his fin de siècle Weekend, a film that tied up all of Godard’s issues with the bourgeoisie and blew them up in an extended car crash in a film that signalled the end of a kind of Godard cinema. The only rule in a Godard film is that there is no rule, so sit back and watch as the master tests his own limits, fumbles for the right riff at the right time, feels around for the right combination of content to cause something, anything… even emotion! Made in USA is a bittersweet goodbye to Anna Karina, who he allows at least to kill the Godard stand in character by shooting him in the head, a fair exchange it seems, in a piece that is fascinating, frustrating, dizzying, amazing and essential.