Tutin triumphs in low key Ken

By Michael Roberts

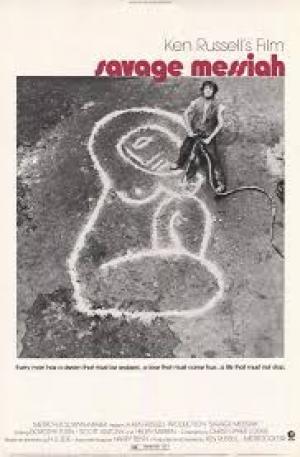

Ken Russell was a man who spent his life immersed in the arts, and film was but one aspect of his interest and expression, music being a huge component, but also dance and theatre. In some ways Russell was a modern equivalent of Michael Powell, or maybe a Michael Powell on acid, an English eccentric who pursued his own idiosyncratic track, with varying and interesting results. Russell was certainly an iconoclast of the first order, and incorporated his uncompromising vision and passion for the arts in all of his work, and coincidentally most of his feature output focused directly on artists of one stripe or another. In Savage Messiah he makes one of his many art bio-pics, this one about a French sculptor, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, and his brief but shining life.

Henri Gaudier was a French painter and drawer, who met the Polish writer Sophie Brzeska in France, when he was 18 and she was twice his age. The pair embarks on an unconventional relationship as they relocate to London pre-WWI and Henri tries his luck with sculpture ("Every blow is a risk"!). The couple struggle in abject poverty, neither able to make a living wage or to accommodate a more ‘normal’ way of living into their bohemian ways. Eventually Henri begins to win some recognition with his work, just as war in Europe threatens everybody’s way of life.

After a decade of directing TV documentaries in the 1960’s, mostly on the lives on prominent artists, Russell was well equipped to handle the dimensions of the Gaudier story. In many ways Russell had already established a language of incorporating an approach to ’art’ in his films, the process of creation being a necessary component of showing an artist’s life in close up. In Savage Messiah he spends a lot of time watching the manual act of creating a canvas or a sculpture, reveling in the connection between the artist and the pure physicality of doing the work. This serves a twofold purpose as Gaudier is very much a man of ‘doing’, whereas Brzeska is a thinker, and this leads to a disconnect in their physical relationship, Brzeska abhorring the sexual act, much to Gaudier’s frustration. Sophie’s solution is a novel one for any era, she pays for prostitutes for her ‘lover’, and the couple continues their symbiotic link.

Russell had a fantastic knack for picking good actors and for bringing out their best, and Savage Messiah is no exception. Scott Antony may not be a household name, but here he plays the sculptor with a wide eyed charm, hinting at what we’d now call ADHD, but avoiding some of the overplaying of Tom Hulce when he played the young Mozart for Amadeus a few years later. The revelation is of course Dorothy Tutin, who plays Sophie, quite simply one of the greatest of all British female film characterisations. Tutin was primarily a theatre performer, and surely great film work was hers for the asking after this film, but she barely made another feature. She embodies the fragility, the hope, the despair and the pure love Sophie had for gaudier, and doesn’t overplay to any degree, a master-class in subtlety and brilliant understatement.

The literate script was written by renowned poet Christopher Logue and Russell again collaborated with Derek Jarman, as he had done on The Devils, on the excellent sets. Helen Mirren makes an early career impression as the suffragist with whom Gaudier has an affair, her descent of a classical staircase a sight to behold. Gaudier was in fact rejecting classical art, “Art is dirt, sex and revolution”, he hollers at the outset. Sophie’s ideal and high minded ethos, art is a “hymn to truth and beauty”, is challenged by Henri’s claim that “Art is as much a mystery to those doing it as to those looking at it”. Ultimately he had the bravery to throw conventions on their head, “I came to Paris to kill myself”, he declares to Sophie shortly after meeting her, clearly making a spiritual break from the art that had come before. In a miraculously short time Gaudier-Brzeska left a legacy of impressive pieces and is seen as a key figure in the widely touted London Group.

Russell financed the film himself, and it did poor business and soon he was Mad Ken, the enfant terrible, making overblown and outrageous films like Liztomania and even Tommy, the very antithesis of the restraint he shows with Savage Messiah, which ironically cleaned up at the box office. Russell illuminated many an artist’s story in his long and uneven career, but never did it as well or as tastefully as with Savage Messiah.

Ps; many thanks to my artist friend Chris Stannard who pointed me to the youtube link for this little seen gem.