Not so pleasant valley sunday

By Michael Roberts

"I look at actors very closely. It's not an accident when the actors excel."

~ John Frankenheimer

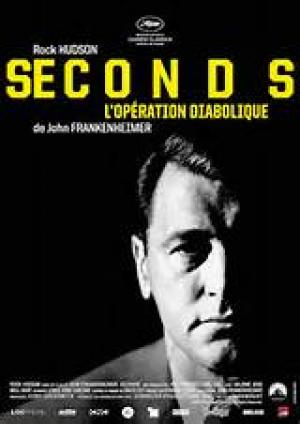

John Frankenheimer was a graduate of the Golden Age of TV in the 1950s, working as an assistant to Sidney Lumet, before moving into feature films. He was a lifelong liberal, worked with Robert Kennedy on his 1968 campaign and gained a reputation as a political filmmaker after the success of The Manchurian Candidate and Seven Days in May, but as evidenced by Seconds, he was able to create fine and subtle cinema of social commentary. Frankenheimer offered Laurence Olivier the chance to play the central character, both before and after plastic surgery, but Paramount refused, and insisted on Rock Hudson, causing the director to shift focus and to use two different actors for before and after. Frankenheimer chose to employ John Randolph for the before section, a Broadway actor still suffering from the Blacklist after an appearance before HUAC in 1955 where he took the Fifth, and in many ways Seconds is a dark -hued allegory for the McCarthy era.

Arthur Hamilton (John Randolph), a respected New York banker, is disturbed by a call from a friend he thought was dead, and is soon drawn into a murky underworld, but one that offers him complete escape from his unhappy life. He signs up to a deal that involves him faking his death and assuming a new identity with a new face after extensive plastic surgery. Arthur Hamilton becomes Tony Wilson (Rock Hudson), an artist living and working in swinging Malibu, a world away from his respectable, staid past. Tony struggles to adapt to his new life but things look up when Nora (Salome Jens), a mysterious and free-spirited woman, enters the picture.

It’s appropriate that Frankenheimer worked with Rod Serling during his TV career, as Seconds comes across as Twilight Zone meets John Cassavettes, with a dash of the French Nouvelle Vague for taste. The film is an examination of the American middle class, as Arthur Hamilton is a man in existential crisis, gazing out of his train commute from Grand Central to leafy Scarsdale, not knowing if he’s coming or going. Arthur has everything the post war consumerist boom promised, a powerful job in loan approvals where he makes or breaks other people’s dreams, a fine home and a devoted and attentive wife, he is a pillar of the establishment in line for the Presidency of his bank.

The trigger for his crisis is a call from his best friend Charlie (Murray Hamilton), the call throws Arthur into a tailspin as Charlie is supposed to be dead. Charlie leads Arthur on a secretive journey that leads him into the offices of The Company. Mr Ruby (Jeff Corey) outlines a scheme by which Arthur can be ‘reborn’, giving the middle aged banker a chance to begin again, a second life. After securing his agreement the Old Man (Will Geer) offers some fatherly words of wisdom, telling Arthur he can have “real freedom”, to realise the “dreams of youth”. The Old Man is a beguiling siren, a devil who whispers into Arthur’s ear about the emptiness of his life and the endless possibilities of re-birth, but the Faustian pact that Arthur makes must come at a cost. Frankenheimer uses some nice visual flourishes to underpin the unease and uncertainty that hangs like a pall over Tony’s life, and introduces a sly reference to death in the black garbed Nora in a moody beach scene worthy of Bergman.

Seconds has widely come to be accepted as the third instalment of Frankenheimer’s ‘Paranoia Trilogy’, completing the set after The Manchurian Candidate and Seven Days in May , and it set a tone that would be explored by others during the Nixon years, notably in Coppola’s, The Conversation and Pakula’s, The Parallax View. The film was part thriller, part horror and part sci-fi, but the hint of an allegory for McCarthyism is unmistakable. Three of the actors involved were victims of the Blacklist, Randolph, Will Geer and Jeff Corey all suffered at the hands of HUAC, as did the iconic cinematographer James Wong Howe, who was grey-listed because his wife was once a Communist. She even left California to live in Mexico for a period to make life easier for Howe, ironic given their marriage was unrecognised in that state for over a decade because of anti-miscegenation laws! Geer must have relished the chance as head of ‘The Company’ to ask Rock Hudson to “ just give me some names”, as he cajoles and pressures, holding out the lure of a second chance, an opportunity to clear the slate and start again. Déjà vu anyone?

The film reserves its most scathing indictment for the empty heart of the materialist American Dream, making it a companion piece to Frankenheimer’s bleak, The Gypsy Moths, which followed soon after. In a remarkable scene Tony goes back home, against the instructions of the Company, where his wife Emily (Frances Reid) unwittingly tells her reconstructed husband some home truths about ‘himself’. “He lived as if he were a stranger here” she tells him, underlining her alienation with, “Arthur was dead a long time before they found him in that hotel room." It’s a sad and sobering moment for a man who has lost everything twice over. The film is also a recognition of the battle of ideas in 1966, between the conservative Establishment and the burgeoning Counter-culture generation, intent on throwing off the legacy of a generation that had delivered a Cold War and a planet on the brink of nuclear annihilation.

Seconds is not without its satirical element, and the tongue-in-cheek component of turning an average Joe into Rock Hudson is nicely acknowledged in the plastic surgeon’s line to his ‘creation’, “You were my masterpiece”. The notion of the Cadaver Procurement Service is nicely underplayed too, and the realisation of exactly where the Company procures its victims from is as chilling a horror moment as any in modern cinema, giving Hudson one of his best scenes. The movie is a revelation, from the stunning Saul Bass title sequence to the final harrowing scenes; it speaks to a duality in the heart of American culture, the libertarian streak that yearns for freedom, as represented by the hedonism of the hippy lifestyle, and the puritan streak that urges against it. It is in the space between where the tension underlying the American Dream exists, a tension that Frankenheimer explored superbly.

John Frankenheimer, despite being labelled a ‘political’ filmmaker, proved himself more than capable in many genres over several decades of significant work. He was a director who didn’t shy away from the tough questions and his best work is still urgent and prescient, full of wit, intelligence and great humanity and none more so than this little seen classic.