O Brother, Where art thou?

By Michael Roberts

'The more you stand in the limelight, the more scarred you will become and the more you will love the limelight.' ~ Preston Sturges

Preston Sturges had been in movies for a dozen years when he wrote and directed Sullivan’s Travels and so had the dirt on how things really worked at the Dream Factory. The film is at once an homage to the movies and a satirical observation of the superficiality and greed that lay behind the production line ethos of the time. Something of a wunderkind himself having had a privileged childhood and been privately educated in France before indulging himself with a penchant for inventing, a kiss-proof lipstick being one such item he came up with for his mother’s cosmetic company, he took up writing after becoming ill and bedridden in the late ’20s. As a playwright he had a hit on Broadway and then went to Hollywood where he worked for Fox and Universal. He was at Paramount for five years before frustration got the better of him and he pitched the idea of directing his own scripts, Paramount agreed after Sturges suggested he’d sell his latest for $1 if he could direct. ’Sullivan’s Travels’ comes midway through his astonishingly productive years as writer-director at Paramount and is arguably as good as any of the eight films he produced.

The fable commences with a dedication to the ‘motley mountebanks, the clowns’… and John L Sullivan (Joel McCrea) , heavyweight directing champion of the world?, is not happy. In a meeting with cigar-chomping studio exec’s he explains he wants to make pictures of social significance, he’s tired of lightweight but profitable productions. The money men don’t want to lose the Golden Goose that is Sully and they humour him while he expounds on his theory and of wanting to make O Brother Where Art Thou?, a film that is ‘the true canvas of the suffering of humanity’, with as the studio heads hope, ‘a little sex’. ‘What do you know of hard luck’? they ask, after he insists he wants to make ‘something like Capra’. At this Sully realises he has no idea what poor people suffer and decides to go undercover as a bum and find out. The studio sees a great promotional opportunity and try to fill the press with positive stories of Sully’s crusade as Sully’s butler cautions that the suffering masses ‘look down on caricaturing of the poor and needy’. Sullivan sets out on the road, accompanied by an entourage and gets involved with a slapstick car chase with a bus, paying tribute to the silent comedy pioneers in the process, but he can’t seem to escape the gravitational pull of Hollywood.

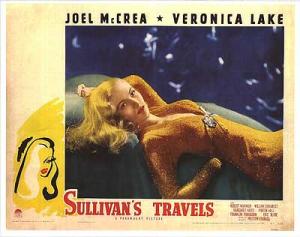

Into the mix Sturges throws the girl, ’there’s always a girl in the picture’, and what a dame with Veronica Lake meeting Sully in a cheap diner and thinking he’s a down-and-out bum she buys him some eggs. Soon she’s in on the con and insists she wants to accompany Sully on his travels. The Girl is a failed actress and Sturges gets in some great lines about what an actress needs to do to get ahead in Hollywood, but she’s not that kind of girl. Eventually the Girl and Sully experience life as hobo’s and it’s no joke, sleeping rough, eating in soup kitchens and showering in communal groups. Sully ends it and they go back to the luxury of his palatial abode. By now he and the Girl are sweet on each other, but as he’d married to get around a tax law, and his wife won’t divorce him, his hands are tied. Sully feels guilt from doing his experiment to profit from his observations so he goes off alone with a pocket full of money to spread amongst the people he’d met, only to be mugged by the same tramp who’d stolen his shoes, the ones with his ID card hidden inside, as fate (and Sturges) would have it. The tramp gets his just reward by being flattened under a train, but as the body is unrecognisable and the only ID found is Sully’s it is announced to the world that John L Sullivan is dead. Sully meanwhile is suffering concussion and wakes up on a freight train only to get into a fight with a railway ‘Bull’, who Sully hits and is dragged before the courts, sentenced to 6 years for assault and as he’s suffering temporary amnesia he’s unable to provide a convincing defence.

Sullivan’s epiphany happens while on the chain gang, after having been brutalised by guards and sent to the sweat box he’s allowed with the men to attend a picture show at the local black church. In some of the most visually poetic scenes the men shuffle in as a screen is lowered and a Walt Disney cartoon is shown (Sturges had wanted to use a Chaplin film, but Charlie wanted too much money). Soon Sully finds himself laughing along with the rest of the congregation, fine contrast to the experience in church he and the Girl had as hobo’s where the pews were full of a bored stiff, captive crowd having to listen to a fire and brimstone sermon in order to be fed. Sully confesses to the murder of John L. Sullivan in order to get some publicity, a subtle nod to the salacious public appetite for all things Hollywood by Sturges, a semi-dark overtone in what is otherwise the happiest of endings, where Sully’s wife had remarried and he’s now free to take up with the girl and write her a ‘letter to Lubitsch’. Sullivan tells the studio brass he’s no longer going to make O Brother, Where Art Thou?, and despite the fact they have announced their huge and important picture. Sullivan tells them, ’there’s something to be said for making people laugh, for some people that’s all they have’.

Sturges is ostensibly justifying his own existence as a comedian, and seeming decrying the trend then rampant in Hollywood towards ‘socially aware’ cinema, but there is more going on. Sturges is lampooning the desire of the studio heads for aggrandizement, the need to be taken seriously by the wider arts community, not ‘serious’ films in themselves, as he also has some significant themes woven into his own work. ie, In this film he has Sully mention that he only got 6 years in prison because the judge thought he was a bum, ‘they don’t sentence Picture director’s for a disagreement with a railroad bull’, pointing out the imbalance in application of the law towards the poor. Sully regrets the fact that pictures could be a major tool of education, and in a pre-television age laments that more is not done in this area, Hollywood mostly existing to make a buck and ignoring any social contract with the people who provide the income. The contrast between the opulence of the successful Hollywood type with the poor in the shantytowns is acute, and it’s not used for comic effect, Sturges is saying ‘this is real’. While he may laud the fact that an entertainment can help them escape their troubles for 90 minutes, he acknowledges they are fated to return to a miserable, grinding life when the credits roll.

Motion Pictures began as the lightweight cousin of painting and literature, and for 40 years had inched toward ‘respectability’ as an art form. The biggest impetus for Hollywood turning towards weightier output was instituting the Academy Awards as self-importance meant films favouring significant issues were more likely to do well with the voters rather than pure escapist entertainments. This created a kind of schizophrenic Hollywood, where studios were prepared to finance ‘prestige’ projects which they knew would most likely fail at the box office, but would do well with the Awards season. Sturges is not sticking it to Capra as much as emulating him, this film has bits of It Happened One Night and Mr Deeds Goes To Town woven through it. The dialogue is witty and as fast paced as any Hawks screwball comedy, and despite the pithy summation at the end, this film has plenty to say. McCrea is fine as the decent and searching Sullivan and Veronica Lake is fantastic as the Girl, a pity she was such a misfit and unable to fulfill the promise this role indicated. Sullivan’s Travels is however Sturges in full flight, a thing of wonder and delight, turning the spotlight in on his own profession and creating a wonderful fable at 24 frames per second in the process.