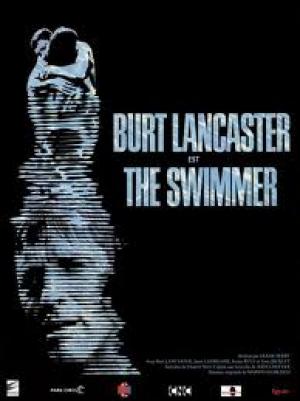

Urban ghost story

By Michael Roberts

"You have to fight against being an antique." ~ Burt Lancaster

Burt Lancaster was always a Hollywood star prepared to push the envelope as an actor and as a producer, never more so than with this 1968 effort directed by Frank Perry. The script, from a New Yorker short story by future Pulitzer Prize winner John Cheever, was written by Perry's wife Eleanor and dissects the upper class hypocrisies and angst in the moneyed and leafy suburbs of Westport, Connecticut. Lancaster carries the film of his own broad shoulders, as it's a veritable one man show for his character as he finds his way home in an unexpected way, bumping into people he's known for years and finding out something about himself in the process. Lancaster and Perry did not get along and Sam Spiegel, the executive producer insisted a penultimate sequence be re-done, at which point Perry walked and Lancaster got Sydney Pollack to direct the scene with a new actress. Spiegel took his own name off the credits. The downbeat fable reflected the sombre mood of the times, America after the consumerist boom of the 1950s was mired in a cold war with the Soviets and a real war in Vietnam as Europe was lurching from crisis to crisis, and the older generation on show were wondering was it all worth it?

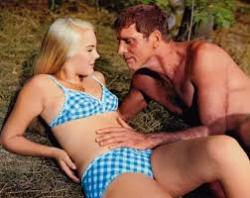

Ned Merrill (Burt Lancaster) emerges from the woods clad only in a swimming costume and walks through the garden of friends to find a warm welcome by the pool. "You're a sight for sore eyes" he's told, "we missed you", and we realise he's been off the social scene for some time. Ned is in high spirits and the banter is light as another couple join and after Ned is done flirting with the women he hits on a scheme, starting with their pool he'll 'swim' home. He maps out a route in his head to walk on to the pools of people he knows until he's at his house across town. "a string of pools forms a river" he says with his eyes gleaming, "the Lucinda river", he says calling it after his wife. Ned sets off to well wishes and bemused looks and his next stop finds an ex high school friend, a woman (Kim Hunter) who he had a crush on, and then he finds Julie (Janet Landgard) a young girl who used to babysit his daughters. Julie joins him for a while in his quest before things start to unravel for Ned, the welcomes are less warm and cracks appear in his good-natured facade. Ned arrives at the house of his former mistress and gets told some home truths, and finally at a public pool some of the depth of his problems are revealed.

The film is a compelling metaphor for the emptiness of relentless consumption as Ned in his pain reveals the fickleness and shallowness of the world he's revisiting. Ned appears almost as Banquo's ghost, a victim of the system that has made the inhabitants fat and rich, but never at any point do they pause to think and reflect on his fall. Ned's peers have built gilded walls around themselves and continue to anesthetise themselves via their drug of choice, for this class mostly hard liquor, as they seek a numbness that blunts any chance of self-awareness. It's plain Ned has had his dark night of the soul, and if he thought he could re-enter the world he left and not open up the scars he was wrong. Eventually Ned's presence is an embarrassment, a reminder that they too could fall from 'grace' and lose their priviliged status, so much so that he moves amongst them like a phantom in the end.

Ned is a man in existential crisis, trying to reconcile a past that has unravelled and to recover his sense of self. "you are the captain of your soul" he tells a young boy who has been deserted by his divorced parents. Ned hints at self discovery, that he's found something true to hold on to, but the illusion can't last, "if you make believe in something hard enough, then it's true for you", as the depths of his delusion bubbles to the surface. What started as a sunny adventure ends in despair, as Ned looks at the sky shivering, "what's the matter with that sun, there's no heat in it?"

Lancaster is very fine as Ned, investing his trademark intensity in a way that keeps unease and tension in play for the entire time, as he seems to be battling his inner conflicts and is barely keeping a lid on his feelings. Lancaster made few friends amongst the cast with his demands and attention to detail, and Joan Rivers who had a small dramatic part at a pool party took seven days to film the scene because of Lancaster's methods. Cast and crew were banned from the rented houses, but Lancaster would knock on their doors and say, "I'm Burt Lancaster, may I have a vodka martini'? Lancaster loved the role and always declared it one of his favourites.

Perry's direction is competent and unobtrusive and allows the dilemma and the action to play out organically, which benefits the film as the puzzle falls gradually into place. Ned seems to come from nature only to be overwhelmed by it finally, as it has overgrown his house and garden and suggests a relentless process that cannot be denied. Ned proceeds from encounters that evoke his youth at the furthest points from his home, to encounters that reveal his troubled recent past the closer he gets to home. Ned looks at a tree stripped bare, not leafy like all the others, in other words his situation in relation to his so-called friends, "the last to get their leaves and the first to lose them" he's told. Ned is outwardly in great shape, inwardly a wreck, a human personification of the stately homes he visits and their fat cat denizens.

The film is an interesting curio and a brave attempt at a mature dissection of important issues. Columbia had no idea how to promote it and it sadly stiffed at the box office. More's the pity as it's a worthy and intelligent piece and a respectable addition to Burt Lancaster's many great cinematic characters and a wonderful entry early in the New Hollywood period as its filming predated Bonnie and Clyde by a year but its release was a year after that landmark piece.