Woody's psychotic over achiever

By Michael Roberts

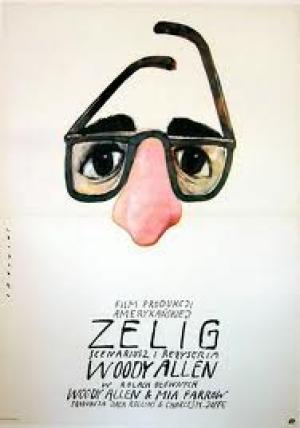

A faux documentary and a heartfelt valentine to the jazz age, 'Zelig' is in many ways, Woody Allen's most remarkable film and easily one of his best. On the back of three reasonably 'serious' pictures in the late '70's, Allen started working on this project, a broader comedy with a serious subtext, and it would take him three years to finish it. While doing 'Zelig' he wrote, produced and starred in 'A Midsummer Night's Sex Comedy' and also filmed 'Broadway Danny Rose', which was released a mere six months after 'Zelig'. The intricacies and the demanding nature of the special effects, achieved in a pre-digital age, were the time consuming aspects of the production but the results were well worth the wait. Allen cast his lover Mia Farrow in the lead, the film was the first started of their 13 eventual collaborations, but the second released. Allen used real intellectuals like Saul Bellow and Susan Sontag to give commentary on the exploits of his hero and this, combined with the newsreel footage of the 20's and 30's, gives the film a seemingly effortless verisimilitude.

In 1928, newspapers start to discover an odd fellow in New York who seems to be taking on the physical characteristics of any people he happens to be around. The famous chronicler, F. Scott Fitzgerald puts a note in his writing about this man he saw at a party, Leonard Zelig (Woody Allen) who he first thought to be an upper class patrician and then later saw him as a lower class servant. Newspapers are looking for any stories to boost circulation, and before long Zelig is a media sensation, seen variously as a fat gangster in a Chicago speakeasy and then as a Black trumpeter at the same club. A young psychologist, Eudora Fletcher (Mia Farrow) takes charge of the case after he is admitted for assessment to her hospital, she battles with other Doctors on the best way to treat Leonard and then loses him to the custody of his sister and her con-man husband. The couple put Leonard on show, charging money to have people see him transform and selling Zelig chameleon dolls. The couple die in a murder-suicide while touring Spain and Leonard again is given into Eudora's custody, with whom he falls in love. A scandal erupts after a showgirl says Leonard got her pregnant and soon several 'wives' come forward and Leonard disappears.

Allen has a tendency for distilling all his neuroses into his hapless protagonists, some with more success than others. Zelig is a hyper version of Allen's latent Jewish wish to assimilate, filtered through the prism of the immigrant experience of the early 20th century, "He wanted to assimilate like crazy" says one of the commentators on Zelig's extreme desire to fit in. Allen presents Leonard as the extrapolation 'par excellence' of the need to be accepted, and then twists the tale, allowing him to show the dark side of 'conforming' in relation to tacit acquiescence. "Life is a meaningless nightmare of suffering" is the advice Zelig gets from his father, who then thoughtfully adds, "save string" and this could well be a pithy summation of Allen's own philosophy. Allen skewers intellectuals and their snobbish superiority, especially the Paris clique who see in Zelig a "symbol of everything", as he suggests the roots of Zelig's problem lay in the fact he lied when he said he'd read Moby Dick. Allen also pricelessly has Zelig adopt the identity of a psychologist when he's with Dr Fletcher, and claim that he was responsible for breaking the concept of penis envy when working with Freud, "but he wanted to limit it to women".

Woody also taps in to the idea of using someone else's personal pain as entertainment, but delivers the lesson at several laughs per minute. A newspaperman commented "you just told the truth and it sold papers, it never happened before"! Zelig is a circus freak, put on show for money, all the while he merely "wants to be liked", and his condition leads him to do anything to be accepted. Allen takes this to it's logical conclusion when Leonard finds himself in Nazi Germany and he fits in by becoming a Nazi, being seen in a group of officers behind Hitler, and causing a ruckus within the group just as Adolph was about to "make a good joke about Poland". Here's the rub of the entire piece, that sublimation of one's sense of self to the point where judgement of right and wrong is compromised is a fraught way to exist. Darwinist's would assert it's a 'herd mentality', and sometimes it takes courage to run against the herd, and in Woody's pragmatic world view courage is a commodity in short supply, so best to focus on love and kindness. As he puts it about Zelig, "It was not the approbation of many but the love of one woman that changed his life".

'Zelig' is a masterpiece of ingenuity, a technical triumph to be sure but also a dazzling conceptual delight that coheres at ever level. An affirmation that all we have is our 'self', and it's worth trying to get in touch with it and fight for it, even if "his taste is lowbrow, but it's his own". Woody Allen would continue his prolificacy but wouldn't spend three years on a single film again. Digital technology would make a similar task infinitely easier today, which goes to underline the primacy of a good or inspired idea. The music is pitch perfect of course, including the slyly written parodies on Leonard, and the love for the era comes through in every frame. Woody would re-visit the era again many years later in his wonderful 'Midnight in Paris", possibly not quite as brilliantly, but damn near, and with such effortless charm the ticket is well worth taking. 'Zelig' will endure as one of his very best.