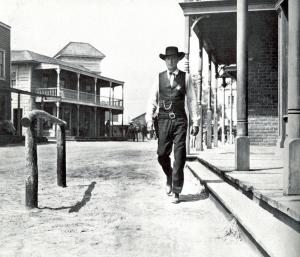

Showdown at the HUAC corral

By Michael Roberts

"First they came for the socialists and I didn’t speak out because I wasn’t a socialist. Then they came for the trade unionists and I didn’t speak out because I wasn’t a trade unionist. Then they came for the Jews and I didn’t speak out because I wasn’t a Jew. Then they came for me, and there was no one left to speak for me". German Pastor Martin Niemöller

Socially progressive producer Stanley Kramer made High Noon as the final project for the independent company he shared with ex-army buddy Carl Foreman, prior to starting a multi-picture deal with Columbia . The pair, having made a success of Brando’s debut feature two years earlier, The Men, with director Fred Zinnemann, again turned to him to helm the Foreman written western, the first of the genre for the émigré Polish-Austrian director. Foreman had the idea for the scenario since 1947, but the eventual filming was five years on and in the interim there had been two separate HUAC investigations into communist activities in the film industry. Foreman was an ex-Communist party member and the pressure he felt to ‘name names’ and appear as a friendly witness is, by his own admission, written deeply into the allegorical nature of the script. The fallout and implications of this are as fascinating as the actual finished film, which is a classic of its kind with or without the HUAC resonances.

Zinnemann’s visual palette is a sombre and washed out black and white, aided by Floyd Crosby's gorgeous cinematography (father of music iconoclast David!) and it gives the mood an almost funereal air, appropriate to the narrative of one man facing a kind of death if he doesn’t act, and an actual death if he does. The opening shot could be a painting, Zinnemann had obviously learnt from Ford’s type of visual poetry, and the mood of menace and revenge is quickly established. Contrasting the desperadoes entering town bent on no good is the happy wedding ceremony of Marshal Will Kane (Gary Cooper) to lovely Quaker Amy Fowler (Grace Kelly), news interrupts the ceremony to inform Kane that Frank Miller is to arrive on the noon train. Miller is a criminal that Kane had put in prison years earlier and had said he’d always return and kill the Marshal. The good people of the town urge Kane to leave, and he sets off at pace in his buggy with his new bride. On the journey out of town Kane realises he can’t run from the fight, he owes it to the town to be the Marshal until the new one arrives, and he owes it to himself to face the danger. Amy is appalled and says she’ll leave him and not stay to become a widow, and Kane then goes off to find support in facing down the outlaw gang.

Foreman uses a couple of vignettes to tease out his theme of ‘good men doing nothing’ and allowing evil to flourish. Kane goes to the judge, who symbolically takes down the flag and the scales of justice as he leaves town, and he tells Kane ‘In Greece in 500 BC a tyrant was driven out of his kingdom by the people, but the tyrant returned with an army of mercenaries and those same citizens stood by while he executed members of the legal government’. Deserted by ‘the law’ Kane turns to the church where a debate takes place about the pros and cons of helping fight the bandits. The women speak out in support as it’s Kane’s work that has civilised the town and made it safe for decent women and children, but some men equivocate and eventually the Mayor (Thomas Mitchell) advises that a fight backed by the town will look bad for outside money interests looking to invest in Hadleyville (read Hollywood) and it would be better if the showdown was seen as one as a personal vendetta involving only Kane and the outlaws. Kane leaves past happy playful children enjoying the freedom he’s dedicated his career for providing.

The perspective of those who will benefit by the outlaws return is provided by a slimy hotel clerk who informs Amy that he’d never liked Kane, and that a lot of townsfolk will be happy to see him get his comeuppance. There is a definite racist undercurrent with the statement, indicating the bigotry that Kane faced by having a past liaison with a Mexican woman once linked to Miller. The undertaker has a quick aside "how many coffins have we got"? and the guys at the bar are eagerly anticipating a return to the ‘wide-open’ town Hadleyville used to be. The line between the law and the lawless is represented by young deputy Harvey Pell (Lloyd Bridges) who joins the mob at the saloon after he’s refused to help Kane who denied him unearned privileges in return. Harvey had corruptly tried to work Kane’s dilemma into an angle that got him the marshal’s job, but Kane wouldn’t stoop to that kind of deal. On a personal level the only one in town who is not surprised by Kane’s stand is another outsider, Helen Ramirez (Katy Jurado) his Mexican ex-girlfriend. Unlike Amy, who comes to discuss the situation with her, "if you don’t understand I can’t tell you", indicates Helen’s core understanding of Kane’s principled stand. She urges Amy to not run, to stand behind her man and fight for him, clearly expressing the depth of her loss in losing her relationship with Kane for reasons that are never specified.

While the plot functions simply as a revenge western in the classic sense, the layers Foreman has woven in that have wider meaning helps to expand the appreciation for the piece. A lone person who has quietly been doing his job is hung out to dry by a community that has been cowed into silence and complicity, unwilling to speak up against a ‘mob’ that has shown scant regard for the law and due process. This is the lot of the people who were called before HUAC, a thinly disguised populist lynch mob hell bent on its own agenda. It’s reasonable that Hollywood was as divided on the issue of how communism was viewed post WWII as the wider society, but the vested interests obviously saw an opportunity to claw back some lost power also, given that anti-monopoly legislation and the ride of the independent producers had changed a landscape once dominated by monolithic studios and their almost hereditary Czars. The studios meekly fell into line with HUAC, cobbling together a sell out agreement at the Waldorf-Astoria, and many conservative actors publicly denounced their ‘pinko’ colleagues, including the iconic Gary Cooper.

An odd postscript is that Cooper, a HUAC 'friendly witness', supported Carl Foreman continuing on the project even though Foreman was called before the committee while High Noon was shooting. This contrasts with the stance taken by Kramer, who for all his liberal values forced Foreman to sell up his share in the company and encouraged his former friend to ‘name names’. Foreman says Kramer was scared for the implications of his long term deal with Columbia, Kramer says Foreman threatened to name him before the committee, (Kramer was a liberal and not an ex-Communist) but in any event Foreman was blacklisted and left for London, never to return. Foremen fell into a depression that brought on a bout of writer's block, drank heavily, lost his family but survived on a healthy settlement from the company he was forced out of. After writing Joseph Losey's hit, The Sleeping Tiger, he wrote David Lean’s superb Bridge on the River Kwai , but was denied a credit and the acknowledgement on the Academy Award it won, a situation that was rectified after in 1984 after Foreman's death.

Ironically Cooper, who may have missed the subtext, won an Oscar for the role, but was too ill to attend the ceremony and asked John Wayne to accept it in his place. John Wayne, who said at the acceptance speech he was sore he didn't get the role, later famously said of the film it was ‘un-American’, disgusted with Kane’s choice at the end to throw away the tin star. Howard Hawks agreed with Wayne and together they made a cinematic reply to High Noon with Rio Bravo, which is a marvellous western in itself, but without the political nuance and subtext. Wayne and his arch-conservatives were responsible for hounding many leftist industry colleagues out of the business via their poisonous organisation, The Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Values.

By any measures High Noon is a great film, and it handles a complex situation superbly. The subtle touches of having strong female roles, one a successful Mexican businesswoman, the other a Quaker who is called to action for love, expanded on the usual ‘horse-opera’ themes and are both expressed effectively in the performances of the lead women, Kelly delicate and nervous, and Jurado deep and passionate. Cooper turned his flagging career around by reminding audiences of his uncommon ‘everyman’ presence, and would more or less repeat the character until his death. Kramer continued his uneven path of social themed productions with mixed success, before moving into direction, again with mixed results, but with several highlights like The Defiant Ones and Judgment at Nuremberg. Zinnemann went on to great success with From Here to Eternity and never made another western, but with this dark toned and sombre masterpiece he delivered one of the great psychological westerns of its era.