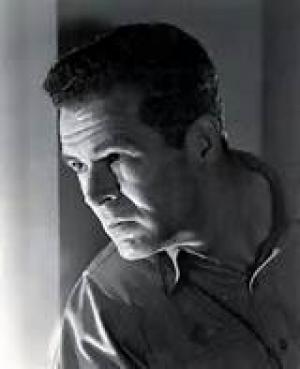

The light beneath the dark

By Michael Roberts

"I think he had a lot of demons.... He certainly talked about his depressions as he got older. And he came from a generation where, if you were a man, you just stuffed all that stuff, as far as the darkness.... He enjoyed a joke, he did like to have a good time. And then there were these days when he would just sort of sit in his room. I think he had ghosts. And what they were, I don't know." ~ Tim Ryan (son)

Robert Ryan emerged amongst a welter of post WWII actors in America, many of whom were veterans of the conflict, and rose to stardom on the back of muscular performances in several excellent Film Noir offerings. Ryan had come to Hollywood hoping to be a writer but his long, lean frame and handsome visage saw him in demand for acting work instead, and his history as a college boxing champion soon led him into contact with director Edward Dmytryk in 1940, who cast him as a boxer in Golden Gloves. Ryan enlisted as a Marine during the war, working as a drill instructor and befriending fellow marine and future writer-director Richard Brooks, before getting his breakthrough role in the filmed version of the Brooks novel, The Brick Foxhole, the liberal-themed Crossfire in 1947, which also reunited him with director Dmytryk, starring opposite Robert Mitchum. That pivotal year also saw him star in French legend Jean Renoir’s final American film, the dream-noir Woman on the Beach, opposite Joan Bennett.

Richard Brooks was a key figure in Ryan’s story, and eventually he would star 20 years later, in Brooks’ excellent western The Professionals, alongside Lee Marvin and Burt Lancaster. Ryan and Brooks were involved with John Huston and Humphrey Bogart in the Committee for the First Amendment, a group of Hollywood liberals that formed as a protest to the putrid HUAC hearings and the so-called communist witch hunt. Ryan’s friend and mentor Edward Dmytryk was gaoled for contempt as a member of the infamous Hollywood Ten, so Ryan also had a personal reason to protest the abuse of government process. Brooks co-wrote (with John Huston) the allegorical Key Largo, as a retort to the hearings, and Ryan seemed to escape unscathed in a career sense as, unlike others, he avoided being caught up in the blacklist.

Crossfire earned Ryan his only Academy Award nomination as Best Supporting Actor and he soon found his métier with A-list directors like Nicholas Ray, Anthony Mann, Robert Wise and Fritz Lang. Ryan’s physicality had him typecast as the heavy or the villain in many of the noir’s, westerns or war films that came his way, ironically so given he was a pacifist and liberal in his personal life. Robert Wise gave him one of his best roles in the earthy and taut The Set-Up, where Ryan’s boxing prowess was again utilized to great advantage, and Ray used him in two excellent dramas, the war film Flying Leathernecks, opposite John Wayne, and the gritty noir, On Dangerous Ground, with Ida Lupino.

Anthony Mann and Fritz Lang both unlocked Ryan’s ability to add an edge of psychotic undertone in his performances; for Mann with his leering villainy in the superb western, The Naked Spur and as the oily misogynist for the German master in Clash by Night. Ryan was the equal to Robert Mitchum as the most dependable and bankable star at RKO during this period, and the two worked together again in John Cromwell’s The Racket. Ryan made a couple of films with Budd Boetticher, including the under-rated western Horizon’s West, before making one of his best films opposite Spencer Tracy in the landmark modern western, the John Sturges helmed Bad Day at Black Rock. Ryan confirmed his stature as a bona-fide A-list star by taking equal billing with Clark Gable in veteran director Raoul Walsh’s The Tall Men.

Robert Wise gave him an excellent role in Odds Against Tomorrow where he again played against his own liberal nature, this time as a racist in a gritty crime themed noir. Ironically, he would often join his co-star in that film, Harry Belafonte, in campaigning for civil rights for African-Americans alongside Dr Martin Luther King and other like minded celebrities. As he moved into the mature, character actor phase of his career he balanced acting challenges like Peter Ustinov’s adaptation of Melville’s Billy Budd with blockbuster mainstream action films like The Longest Day and Battle of the Bulge.

Ryan stayed relevant and viable by making huge commercial hits in The Professionals for Brooks and again with the John Sturges war blockbuster, The Dirty Dozen. He starred again for Sturges in another re-telling of the Wyatt Earp versus the Clanton’s yarn in Hour of the Gun, and made the definitive modern western for maverick Sam Peckinpah in the iconic The Wild Bunch in 1969. Ryan finished his career with a couple of fine films with his good friend Burt Lancaster, in Lawman and Executive Action, and made his last feature with John Frankenheimer’s version of Eugene O’Neill’s The Iceman Cometh, opposite Lee Marvin and Frederic March. Ryan died of cancer in 1973 at the age of relatively young age of 63.

Robert Ryan was something of a man out of time, coming to notice during the Brando-Clift era of young method actors who took Hollywood by storm after WWII. Ryan’s raw physicality saw him typecast into roles that were far from his own personal ethos and evoked the classic machismo of Gable and Cooper, rather than the duality of masculine/feminine that the new breed of method actors explored. Ryan was a fine actor who mastered the art of quiet expression, of filling his many villainous characters with believability, charisma and humanity, which made for dimensional and convincing heavies a la Hitchcock’s much quoted maxim

"He was incredibly shy, although—I guess this is what actors can do—he could just turn on when the situation called for that. But basically he was a very quiet, introverted guy. You wonder, looking at some of the parts that he played in movies, what it was in him that was able to access those really dark, scary characters." ~ Lisa Ryan (daughter)

Neither as manic as Richard Widmark nor as dismissingly insouciant and cool as his great contemporary Robert Mitchum, Ryan carved out a solid place for himself in American cinema nonetheless. If he’d had a softer look he may have been given the roles that someone like Henry Fonda attracted, an actor who shared his personal philosophies and liberalism, but Ryan was fated to provide a gallery of rogues, villains and scoundrels that linger in the memory due to his committed performances and honest characterisations, served with heart and verve with nary a false note in sight.